Views

Adoption of the ‘Lisbon Guidelines on Privacy’ at the 80th Biennial Conference of the International Law Association

On 23 June 2022, the Lisbon Guidelines on Privacy, drawn up by the ILA Committee on the Protection of Privacy in Private International and Procedural Law, were formally endorsed by the International Law Association at the 80th ILA Biennial Conference, hosted in Lisbon (Portugal).

The Committee was established in 2013 further to the proposal of Prof. Dr. Dres. h.c. Burkhard Hess (Director at the Max Planck Institute Luxembourg) to create a forum on the protection of privacy in the context of private international and procedural law. Prof. Dr. Dres. h.c. Burkhard Hess chaired the Committee, and Prof. Dr. Jan von Hein (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) and Dr. Cristina M. Mariottini (Max Planck Institute Luxembourg) were the co-rapporteurs.

In accordance with the mandate conferred by the International Law Association, the Committee – which comprised experts from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America – focussed on the promotion of international co-operation and the contribution to predictability on issues of jurisdiction, applicable law, and circulation of judgments in privacy (including defamation) matters, taking into account, i.a., questions of fundamental rights. In this framework, the Committee expanded its analysis also to the questions arising from the interface of privacy with personal data protection.

The Guidelines are premised on two fundamental principles: notably, (i) foreseeability of jurisdiction, and (ii) parallelism between jurisdiction and applicable law. They are accompanied by a detailed Article-by-Article Commentary, which provides a comprehensive analysis of the Guidelines, complemented by examples, including illustrations taken from copious national, regional and supranational jurisprudence.

Overall, the Committee took note of the fact that, in spite of the differences between legal systems, constitutional values play a major role in the legal treatment of privacy. In particular, substantial layers of public law enter into the equation of private enforcement of privacy. This notion and the limits that stem from the impact that such layers of public law forcibly have on claims must be taken into due consideration with respect to the jurisdiction as well as to the law applicable to these claims and bear a remarkable impact on the subsequent eligibility of privacy judgments for circulation.

Against this background, the Committee proceeded to design a system based, in essence and subject to substantiated exceptions, on the foreseeability of jurisdiction and a principled parallelism between jurisdiction and applicable law. The latter approach has the advantage of saving time and costs, but must be balanced against the danger of forum shopping. In so far, the approach of the Guidelines (Article 7) distinguishes between jurisdiction based on the defendant’s conduct (Article 3) and jurisdiction localized at the defendant’s habitual residence (Article 4). While a defendant’s conduct that is significant for establishing jurisdiction will usually also indicate a sufficiently close connection for choice-of-law purposes, the general jurisdiction at the defendant’s habitual residence is rather neutral in this regard and thus complemented by a specific conflicts rule. Moreover, a necessary degree of flexibility is introduced by providing for party autonomy (Article 9) and an escape clause (Article 8). In order to take into account that personality rights and privacy protection are rooted in constitutional values, Article 11 contains a provision on public policy and overriding mandatory rules.

The Committee was cognizant that, to date, the recognition and enforcement of a foreign judgment on privacy rights is a matter primarily governed by national law. In response to this status quo, the Guidelines design a system for the recognition and enforcement of foreign privacy judgments that pursues consistency and continuity (esp. Article 12) with the rules on jurisdiction while also taking into account the characteristic objections to and obstacles that in many instances preclude the circulation of judgments that fall in the scope of the Guidelines (Article 13).

The adoption of the Guidelines marks the completion of the Committee’s mandate.

Traveling Judges and International Commercial Courts

Written by Alyssa S. King and Pamela K. Bookman

International commercial courts—domestic courts, chambers, and divisions dedicated to commercial or international commercial disputes such as the Netherlands Commercial Court and the never-implemented Brussels International Business Court—are the topic of much discussion these days. The NCC is a division of the Dutch courts with Dutch judges. The BIBC proposal, however, envisioned judges who were mostly “part-timers” who may include specialists from outside Belgium. While the BIBC experiment did not pass Parliament, other commercial courts around the world have proliferated, and some hire judges from outside their jurisdictions.

In a new paper forthcoming in the American Journal of International Law, we set out to determine how many members of the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts hire such “traveling judges,” who they are, why they are hired, and why they serve.

Based on new empirical data and interviews with over 25 judges and court personnel, we find that traveling judges are found on commercially focused courts around the world. We identified nine jurisdictions with such courts, in Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Qatar, Kazakhstan, and the Caribbean (the Cayman Islands and the BVI), and The Gambia. These courts are designed to accommodate foreign litigants and transnational litigation—and inevitably, conflicts of laws.

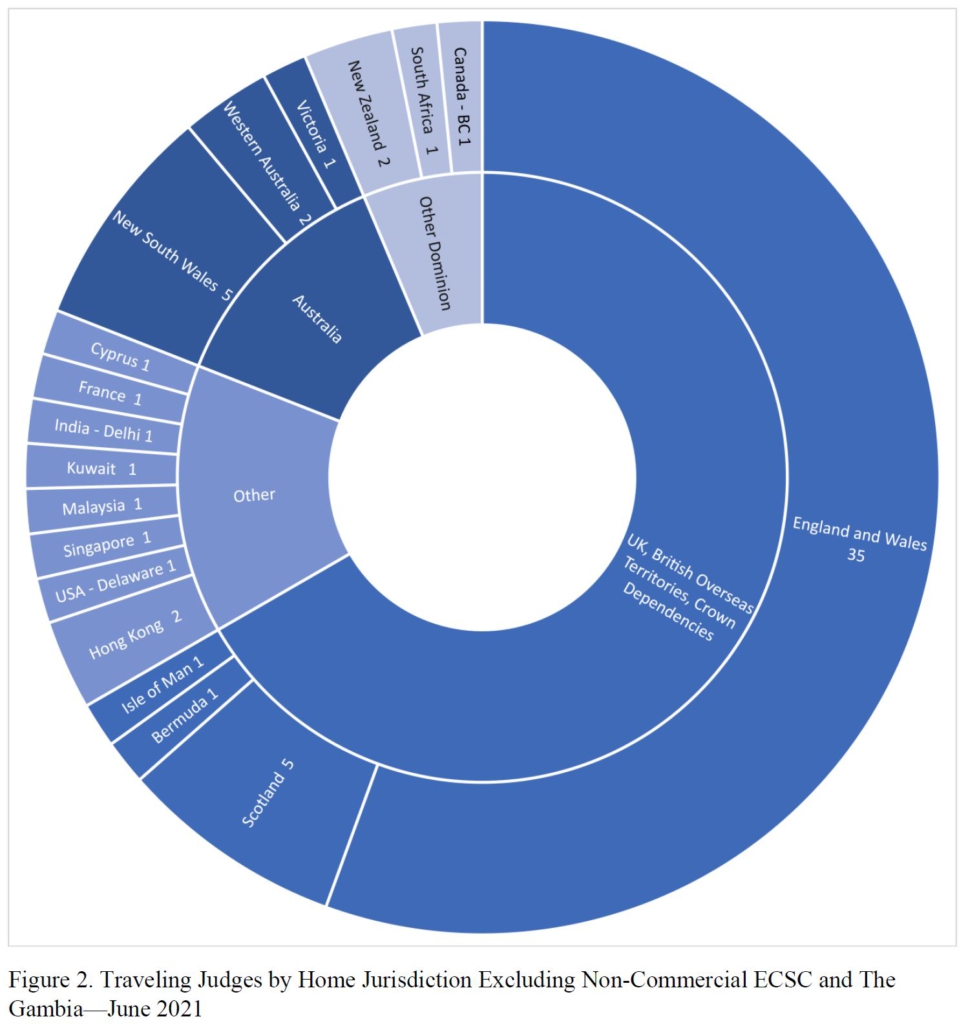

One may assume that these judges largely resemble arbitrators (as was likely intended for the BIBC). But whereas studies show arbitrators are mostly white, male lawyers from “developed” countries that may be based in the common law or civil law tradition, traveling judges are even more likely to be white and male, vastly more likely to have prior judicial experience and common-law legal training, and are overwhelmingly from the UK and its former dominion colonies. In the subset of commercially focused courts in our study, just over half of the traveling judges were from England and Wales specifically. Nearly two-thirds had at least one law degree from a UK university.

Below is a chart showing the home jurisdiction of the judges in our study. This includes traveling judges sitting on the BVI commercial division, Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal, Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) Courts, Qatar International Court, Cayman Islands Financial Services Division, Singapore International Commercial Court, Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Courts, and Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) Courts as of June 2021.

A look at traveling judges’ backgrounds suggests that traveling judges might be a phenomenon limited to common-law countries, but only half of hiring jurisdictions are in common law states. Almost all hiring jurisdictions, however, are common law jurisdictions. Moreover, almost all are or aspire to be market-dominant small jurisdictions (MDSJ). For example, the DIFC Courts are located in a common law jurisdiction within a non-common-law state that has been identified as a MDSJ.

Traveling judges are a phenomenon rooted not only in the rise of international commercial arbitration, but also in the history of the British colonial judicial service. Today, traveling judges may be said to bring their expertise and knowledge of best practices in international commercial dispute resolution. But traveling judges also offer hiring jurisdictions a method of transplanting well-respected courts, like London’s commercial court, on their shores. In doing so, judges reveal these jurisdictions’ efforts to harness business preferences for English common law into their domestic court systems. They also provide further opportunities for convergence on global civil procedure norms, or at least common law ones. Many courts have adopted some version of the English Civil Procedure Rules, looking for something international lawyers find familiar and reliable. Judges also report learning from each other’s approaches.

Our article suggests that traveling judges are a nearly entirely common law phenomenon—only a handful of judges were from mixed jurisdictions and only one was a civil law judge. Common law courts may be especially amenable to traveling judges. In contrast to judges in continental civil law systems, common law judges are not career bureaucrats. They come to the judiciary late, usually after having built successful litigation practices. Moreover, the sociologist, and judge, Antoine Garapon observes that common law style-judging can be more personalized, with more room for individual authority rather than that of the office. All these differences are a matter of degree, with exceptions that come readily to mind. Still, as a result, common law judges are more likely have reputations independent of the office they serve. That reputation, in turn, is valuable to hiring governments eager to demonstrate their commercial law bona fides.

These efforts to harness English common law contrast with the efforts to build international commercial courts in the Netherlands or Belgium. The NCC advertises itself as an English-language court built on the foundation of the Dutch judiciary’s strong reputation. As such, it has no need for foreign judges or common law experience. The BIBC likely also would not have relied as heavily on retired English judges, both because its designers envisioned more lay adjudicators (not retired judges) and likely a greater civil law influence. In that sense, its roster of judges might have more closely resembled that of the new international commercial court in Bahrain.

The Dutch, Belgian, and Bahraini examples do share something else in common with the network of courts profiled in Traveling Judges, however. Despite their apparent similarities to arbitration, these courts are domestic courts, and they exist in significantly different political environments. The differences between Dutch and Belgian national politics influenced the NCC’s success in being established and the BIBC’s failure. In Belgium, for instance, the BIBC was maligned as a “caviar court” for foreign companies and the Belgian Parliament ultimately decided against the proposal. As one of us recounts in a related article on arbitration-court hybrids, similar arguments were raised in the Dutch Parliament, but they did not win the day. Several courts in our study, such as those established in the special economic zones in the UAE, did not face such constraints. But they may face others, such as how local courts will recognize and cooperate with a new court operating according to a different legal system and in a different language. The new court in Bahrain overcame local obstacles to its establishment, but it may face yet another set of political constraints and pressures as it proceeds to hear its first cases. Wherever traveling judges travel, local politics will affect both hiring jurisdictions’ ability to achieve their goals and traveling judges’ ability to judge in the way they are accustomed.

American Society of International Law Newsletter and Commentaries on Private International Law

American Society of International Law Private International Law Interest Group is pleased to publish the newest Newsletter and Commentaries on Private International Law (Vol. 5, Issue 1) on PILIG webpage. The primary purpose of our Newsletter is to communicate global news on PIL. It attempts to transmit information on new developments on PIL rather than provide substantive analysis, in a non-exclusive manner, with a view of providing specific and concise information that our readers can use in their daily work. These updates on developments on PIL may include information on new laws, rules, and regulations; new judicial and arbitral decisions; new treaties and conventions; new scholarly work; new conferences; proposed new pieces of legislation; and the like.

This issue has three sections. Section one contains Highlights on cultural heritage protection and applicable law in the US and recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments in China. Section two reports on the recent developments on PIL in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America. Section Three overviews global development.

News

The American Branch of the International Law Association is seeking a new Chief Operating Officer

Second edition of The Hague Academy of International Law’s Advanced Course in Hong Kong on “Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters: Judgments Convention”

From 2 to 6 December 2024, the second edition of The Hague Academy of International Law’s Advanced Course in Hong Kong was held, co-organised by the Asian Academy of International Law (AAIL) with the support of the Department of Justice of the Government of the Hong Kong SAR. Once again, the Hague Academy of International Law brought distinguished speakers to the “fragrant harbour” to deliver lectures on the “Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters”. Just a stone’s throw from the Old Supreme Court Building (now the seat of Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal) at the premises of the Hong Kong Club, legal scholars, national judges, government officials and legal practitioners from over 20 jurisdictions as diverse as Laos, the People’s Republic of China, (francophone) Cameroon, The Netherlands, South Africa or the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia came together to discuss their respective experiences and the prospects of the latest instrument in this field, the HCCH 2019 Judgments Convention.

[Now Available] Yearbook of Private International Law Vol. XXV – 2023/2024

The latest volume of the Yearbook of Private International Law has been recently published, marking the 25th anniversary of its significant contribution to outstanding legal scholarship in the field of comparative private international law.

The latest volume of the Yearbook of Private International Law has been recently published, marking the 25th anniversary of its significant contribution to outstanding legal scholarship in the field of comparative private international law.

Readers will undoubtedly appreciate the Editors’ Foreword as well as the insightful tributes dedicated to this milestone edition written by Professors Nadjma Yassari (A Quarter-Century of Excellence), Symeon C. Symeonides (A Tribute), and Ivana Kunda (Petar Šarcevic – The Intellectual Behind the Name). These contributions, which reflect on the Yearbook’s impact and achievements over the years, are freely available online, offering a fitting celebration of this remarkable anniversary.

The Yearbook’s latest volume features the following table of contents: Read more