Views

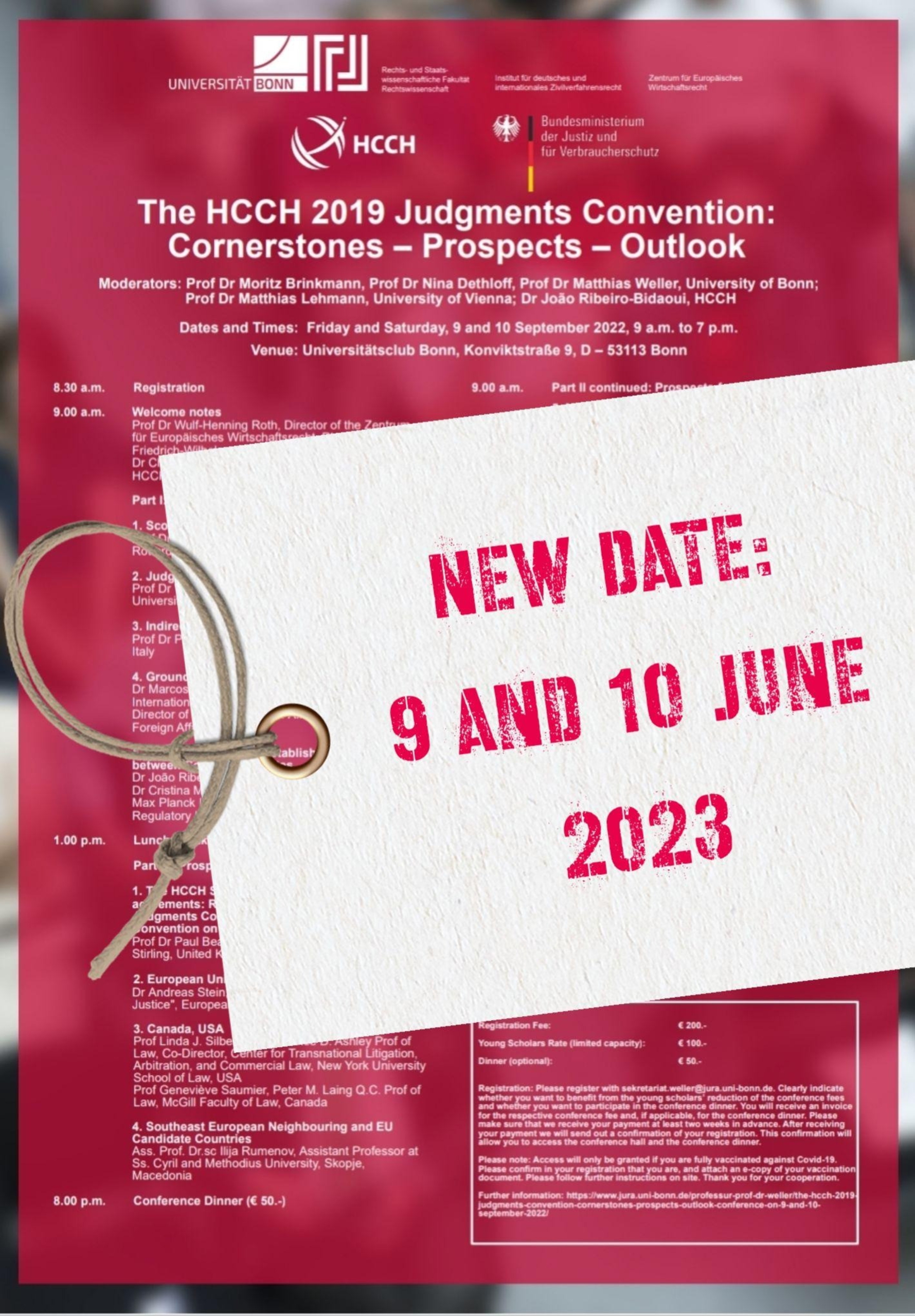

Conference on “The HCCH 2019 Judgments Convention: Cornerstones, Prospects, Outlook” – Rescheduled to 9 and 10 June 2023

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

Due to a conflicting conference on the previously planned date (9 and 10 September 2022) and with a view to ongoing developments on the subject-matter in the EU, we have made the decision to reschedule our Conference to Friday and Saturday, 9 and 10 June 2023. This new date should bring us closer to the expected date of accession of the EU and will thus give the topic extra momentum. Stay tuned and register in time (registration remains open)!

On 23 June 2022, the European Parliament by adopting JURI Committee Report A9-0177/2022 gave its consent to the accession of the European Union to the HCCH 2019 Judgments Convention. The Explanatory Statement describes the convention with a view to the “growth in international trade and investment flows” as an “instrument […] of outmost importance for European citizenz ans businesses” and expressed the hope that the EU’s signature will set “an example for other countries to join”. However, the Rapporteur, Ms. Sabrina Pignedoli, also expresses the view that the European Parliament should maintain a strong role when considering objections under the bilateralisation mechanism provided for in Art. 29 of the Convention. Additionally, some concerns were raised regarding the protection of employees and consumers under the instrument. For those interested in the (remarkably fast) adoption process, the European Parliament’s vote can be rewatched here. Given these important steps towards accession, June 2023 should be a perfect time to delve deeper into the subject-matter, and the Conference is certainly a perfect opportunity for doing so:

The list of speakers of our conference includes internationally leading scholars, practitioners and experts from the most excellent Universities, the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH), the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), and the European Commission (DG Trade, DG Justice). The Conference is co-hosted by the Permanent Bureau of the HCCH.

The Organizers kindly ask participants to contribute with EUR 200.- to the costs of the event and with EUR 50.- to the conference dinner, should they wish to participate. There is a limited capacity for young scholars to contribute with EUR 100.- to the conference (the costs for the dinner remain unchanged).

Please register with sekretariat.weller@jura.uni-bonn.de. Clearly indicate whether you want to benefit from the young scholars’ reduction of the conference fees and whether you want to participate in the conference dinner. You will receive an invoice for the respective conference fee and, if applicable, for the conference dinner. Please make sure that we receive your payment at least two weeks in advance. After receiving your payment we will send out a confirmation of your registration. This confirmation will allow you to access the conference hall and the conference dinner.

Please note: Access will only be granted if you are fully vaccinated against Covid-19. Please confirm in your registration that you are, and attach an e-copy of your vaccination document. Please follow further instructions on site, e.g. prepare for producing a current negative test, if required by University or State regulation at that moment. We will keep you updated. Thank you for your cooperation.

Dates and Times:

Friday, 9 June 2023, and Saturday, 10 September 2023, 9 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Venue:

Universitätsclub Bonn, Konviktstraße 9, D – 53113 Bonn

Registration:

sekretariat.weller@jura.uni-bonn.de

Registration fee: EUR 200.-

Programme

Friday, 9 June 2023

8.30 a.m. Registration

9.00 a.m. Welcome notes

Prof Dr Wulf-Henning Roth, Director of the Zentrum für Europäisches Wirtschaftsrecht, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Germany

Dr Christophe Bernasconi, Secretary General of the HCCH

Part I: Cornerstones

1. Scope of application

Prof Dr Xandra Kramer, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands

2. Judgments, Recognition, Enforcement

Prof Dr Wolfgang Hau, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, Germany

3. Indirect jurisdiction

Prof Dr Pietro Franzina, Catholic University of Milan, Italy

4. Grounds for refusal

Dr Marcos Dotta Salgueiro, Adj. Professor of Private International Law, Law Faculty, UR, Uruguay; Director of International Law Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Uruguay

5. Trust management: Establishment of relations between Contracting States

Dr João Ribeiro-Bidaoui, First Secretary, HCCH / Dr Cristina Mariottini, Senior Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for International, European and Regulatory Law Luxemburg

1.00 p.m. Lunch Break

Part II: Prospects for the World

1. The HCCH System for choice of court agreements: Relationship of the HCCH Judgments Convention 2019 to the HCCH 2005 Convention on Choice of Court Agreements

Prof Dr Paul Beaumont, University of Stirling, United Kingdom

2. European Union

Dr Andreas Stein, Head of Unit, DG JUST – A1 “Civil Justice”, European Commission

3. Canada, USA

Prof Linda J. Silberman, Clarence D. Ashley Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center for Transnational Litigation, Arbitration, and Commercial Law, New York University School of Law, USA

Prof Geneviève Saumier, Peter M. Laing Q.C. Professor of Law, McGill Faculty of Law, Canada

4. Southeast European Neighbouring and EU Candidate Countries

Ass. Prof. Dr.sc Ilija Rumenov, Assistant Professor at Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Skopje, Macedonia

8.00 p.m. Conference Dinner (EUR 50.-)

Saturday, 10 June 2023

9.00 a.m. Part II continued: Prospects for the World

5. Middle East and North Africa (including Gulf Cooperation Council)

Prof Dr Béligh Elbalti, Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Law and Politics at Osaka University, Japan

6. Sub-Saharan Africa (including Commonwealth of Nations)

Prof Dr Abubakri Yekini, University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Prof Dr Chukwuma Okoli, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom

7. Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR)

Prof Dr Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm, Director of Internationalisation, Senior Lecturer in International Private Law, School of Law, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom

8. Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

Prof Dr Adeline Chong, Associate Professor of Law, Yong Pung How School of Law, Singapore Management University, Singapore

9. China (including Belt and Road Initiative)

Prof Dr Zheng (Sophia) Tang, University of Newcastle, United Kingdom

1.00 p.m. Lunch Break

Part III: Outlook

1. Lessons from the Genesis of the Judgments Project

Dr Ning Zhao, Senior Legal Officer, HCCH

2. International Commercial Arbitration and Judicial Cooperation in civil matters: Towards an Integrated Approach

José Angelo Estrella-Faria, Principal Legal Officer and Head, Legislative Branch, International Trade Law Division, Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations; Former Secretary General of UNIDROIT

3. General Synthesis and Future Perspectives

Hans van Loon, Former Secretary General of the HCCH

First Instance where a Mainland China Civil Mediation Decision has been Recognized and Enforced in New South Wales, Australia

I Introduction

Bank of China Limited v Chen [2022] NSWSC 749 (‘Bank of China v Chen’), decided on the 7 June 2022, is the first instance where the New South Wales Supreme Court (‘NSWSC’) has recognised and enforced a Chinese civil mediation decision.

II Background

This case concerned the enforcement of two civil mediation decisions obtained from the People’s Court of District Jimo, Qingdao Shi, Shandong Province China (which arose out of a financial loan dispute) in Australia.[1]

A foreign judgement may be enforced in Australia either at common law or pursuant to the Foreign Judgements Act 1991(Cth).[2] As the People’s Republic of China is not designated as a jurisdiction of substantial reciprocity under the Foreign Judgements Regulation 1992 (Cth) schedule 1, the judgements of Chinese courts may only be enforced at common law.[3]

For a foreign judgement to be enforced at common law, four requirements must be met:[4] (1) the foreign court must have exercised jurisdiction in the international sense; (2) the foreign judgement must be final and conclusive; (3) there must be identity of parties between the judgement debtor(s) and the defendant(s) in any enforcement action; and (4) the judgement must be for a fixed, liquidated sum. The onus rests on the party seeking to enforce the foreign judgement.[5]

Bank of China Ltd (‘plaintiff’) served the originating process on Ying Chen (‘defendant’) pursuant to r 11.4 and Schedule 6(m) of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) (‘UCPR’) which provides that an originating process may be served outside of Australia without leave of the court to recognise or enforce any ‘judgement’.[6] Central to this dispute was whether a civil mediation decision constituted a ‘judgement’ within the meaning of schedule 6(m).

III Parties’ Submission

A Defendant’s Submission

The defendant filed a notice of motion seeking for (1) the originating process to be set aside pursuant to rr 11.6 and 12.11 of the UCPR, (2) service of the originating process on the defendant to be set aside pursuant to r 12.11 of the UCPR and (3) a declaration that the originating process had not been duly served on the defendant pursuant to r 12.11 of the UCPR.[7]

The defendant argued that the civil mediation decisions are not ‘judgements’ within the meaning of UCPR Schedule 6(m).[8] Moreover, the enforcement of foreign judgment at common law pre-supposes the existence of a foreign judgement which is absent in this case.[9]

The defendant submitted that the question that must be asked in this case is whether the civil mediation decisions were judgements as a matter of Chinese law which is a question of fact.[10] This was a separate question to whether, as a matter of domestic law, the foreign judgements ought to be recognised at common law.[11]

B Plaintiff’s Submission

In response, the plaintiff submitted that all four common law requirements were satisfied in this case.[12] Firstly, there was jurisdiction in the international sense as the defendant appeared before the Chinese Court by her authorised legal representative.[13] The authorised legal representative made no objection to the civil mediation decisions.[14] Secondly, the judgement was final and conclusive as it was binding on the parties, unappealable and can be enforced without further order.[15] Thirdly, there was an identity of parties as Ying Chen was the defendant in both the civil mediation decisions and the enforcement proceedings.[16] Fourthly, the judgement was for a fixed, liquidated sum as the civil mediation decisions provided a fixed amount for principal and interest.[17]

In relation to the defendant’s notice of motion, the plaintiff argued that the question for the court was whether the civil mediation decisions fell within the meaning of ‘judgement’ in the UCPR, that is, according to New South Wales law, not Chinese law (as the defendant submitted).[18] On this question, there was no controversy.[19] While the UCPR does not define ‘judgement’, the elements of a ‘judgement’ are well settled according to Australian common law and Chinese law expert evidence supports the view that civil mediation decisions have those essential elements required by Australian law.[20]

Under common law, a judgement is an order of Court which gives rise to res judicata and takes effect through the authority of the court.[21] The plaintiff relied on Chinese law expert evidence which indicated that a civil mediation decision possesses those characteristics, namely by establishing res judicata and having mandatory enforceability and coercive authority.[22] The expert evidence noted that a civil mediation decision is a type of consent judgement resulting from mediation which becomes effective once all parties have acknowledged receipt by affixing their signature to the Certificate of Service.[23] The Certificate of Service in respect of the civil mediation decisions in this case had been signed by the legal representatives of the parties on the day that the civil mediation decisions were made.[24] While a civil mediation decision is distinct to a civil judgement,[25] a civil mediation decision nonetheless has the same binding force as a legally effective civil judgement and can be enforced in the same manner.[26]

The expert evidence further noted that Mainland China civil mediation decisions have been recognised and enforced as foreign judgements in the Courts of British Columbia, Hong Kong and New Zealand.[27] The factors which characterise a ‘judgement’ under those jurisdictions are the same factors which characterise a ‘judgement’ under Australian law.[28]This supports the view that the same recognition should be afforded under the laws of New South Wales.[29]Accordingly, the plaintiff submitted the a civil mediation decision possesses all the necessary characteristics of a ‘judgement’ under Australian law such that service could be effected without leave under schedule 6(m).[30]

IV Resolution

Harrison AsJ noted that the judgements of Chinese courts may be enforceable at common law and found that all four requirements was satisfied in this case.[31] There was jurisdiction in the international sense as the defendant’s authorised legal representative appeared before the People’s Court on her behalf, the parties had agreed to mediation, the representatives of the parties came to an agreement during the mediation, and this was recorded in a transcript.[32] The parties’ representatives further signed the transcript and a civil mediation decision had been issued by the people’s courts.[33] Moreover, the civil mediation decision was final and binding as it had been signed by the parties.[34] The third and fourth requirements were also clearly satisfied in this case.[35]

In relation to the central question of whether the civil mediation decisions constituted ‘judgements’ in the relevant sense, Harrison AsJ found in favour of the plaintiff.[36] Harrison AsJ first noted that this question should not be decided on the arbitrary basis of which of the many possible translations should be preferred.[37] Moreover, the evidence of the enforcement of civil mediation decisions as judgements in the jurisdictions of British Columbia, Hong Kong and New Zealand was helpful, though also not determinative.[38]

Rather, this question must be determined by reference to whether civil mediation decisions constituted judgements under Australian law as opposed to Chinese law, accepting the plaintiff’s submission.[39] The civil mediation decisions were enforceable against the defendant immediately according to their terms in China without the need for further order or judgement of the People’s Court.[40] The parties could not vary or cancel the civil mediation decisions without the permission of the Jimo District Court.[41] The civil mediation decisions also had the same legal effects as a civil judgement.[42] Therefore, Harrison AsJ concluded that the civil mediation decisions were judgements for the purposes of Australian law as they established res judicata and were mandatorily enforceable and had coercive authority.[43] It then followed that the civil mediation decisions fell within the scope of UCPR schedule 6(m) and did not require leave to be served.[44]

V Orders

In light of the analysis above, Harrison AsJ held that the Chinese civil mediation decisions were enforceable and dismissed the defendant’s motion.[45] Costs were further awarded in favour of the plaintiff.[46]

Author: Hao Yang Joshua Mok, LLB Student at the University of Sydney Law School

Supervised by Associate Professor Jeanne Huang, Sydney Law School

References:

[1] Bank of China Limited v Chen [2002] NSWSC 749, [1], [16].

[2] Ibid [8]; citing Bao v Qu; Tian (No 2) [2020] NSWSC 588, [23]-[29].

[3] Ibid [8].

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid [9] – [11].

[7] Ibid [6].

[8] Ibid [57].

[9] Ibid [59], [84].

[10] Ibid [61].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid [25].

[13] Ibid [18].

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid [20].

[16] Ibid [22].

[17] Ibid [24].

[18] Ibid [27].

[19] Ibid [28].

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid [37].

[22] Ibid [38].

[23] Ibid [39].

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid [41].

[26] Ibid [42].

[27] Ibid [49].

[28] Ibid [50].

[29] Ibid [51].

[30] Ibid [52].

[31] Ibid [83], [90].

[32] Ibid [86].

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid [87].

[35] Ibid [88]-[89].

[36] Ibid [105].

[37] Ibid [91]-[92].

[38] Ibid [93].

[39] Ibid [96].

[40] Ibid [103].

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid [105].

[44] Ibid [106].

[45] Ibid [107]-[108].

[46] Ibid [109]-[112].

Golan v. Saada – a case on the HCCH Child Abduction Convention: the Opinion of the US Supreme Court is now available

Written by Mayela Celis, UNED

Yesterday (15 June 2022) the US Supreme Court rendered its Opinion in the case of Golan v. Saada regarding the HCCH Child Abduction Convention. The decision was written by Justice Sotomayor, click here. For our previous analysis of the case, click here.

This case dealt with the following question: whether upon finding that return to the country of habitual residence places a child at grave risk, a district court is required to consider ameliorative measures that would facilitate the return of the child notwithstanding the grave risk finding. (our emphasis)

In a nutshell, the US Supreme Court answered this question in the negative. The syllabus of the judgment says: “A court is not categorically required to examine all possible ameliorative measures [also known as undertakings] before denying a Hague Convention petition for return of a child to a foreign country once the court has found that return would expose the child to a grave risk of harm.” The Court has also wisely concluded that “Nothing in the Convention’s text either forbids or requires consideration of ameliorative measures in exercising this discretion” (however, this is different in the European Union context where a EU regulation complements the Child Abduction Convention).

While admittedly not everyone will be satisfied with this Opinion, it is a good and well-thought through decision that will make a great impact on how child abduction cases are decided in the USA; and more broadly, on the way we perceive what the ultimate goal of the treaty is and how to strike a right balance between the different interests at stake and the need to act expeditiously.

In particular, the Court stresses that the Convention “does not pursue return exclusively or at all costs”. And while the Court does not make a human rights analysis, it could be argued that this Opinion is in perfect harmony with the current approaches taken in human rights law.

In my view, this is a good decision and is in line with our detailed analysis of the case in our previous post. In contrast to other decisions (see recent post from Matthias Lehmann), for Child Abduction – and human rights law in general – this is definitely good news from Capitol Hill.

Below I include a few excerpts of the decision (our emphasis, we omit footnotes):

“In addition, the court’s consideration of ameliorative measures must be guided by the legal principles and other requirements set forth in the Convention and ICARA. The Second Circuit’s rule, by instructing district courts to order return “if at all possible,” improperly elevated return above the Convention’s other objectives. Blondin I, 189 F. 3d, at 248. The Convention does not pursue return exclusively or at all costs. Rather, the Convention “is designed to protect the interests of children and their parents,” Lozano, 572 U. S., at 19 (ALITO , J., concurring), and children’s interests may point against return in some circumstances. Courts must remain conscious of this purpose, as well as the Convention’s other objectives and requirements, which constrain courts’ discretion to consider ameliorative measures

in at least three ways.

“First, any consideration of ameliorative measures must prioritize the child’s physical and psychological safety. The Convention explicitly recognizes that the child’s interest in avoiding physical or psychological harm, in addition to other interests, “may overcome the return remedy.” Id., at 16 (majority opinion) (cataloging interests). A court may therefore decline to consider imposing ameliorative measures where it is clear that they would not work because the risk is so grave. Sexual abuse of a child is one example of an intolerable situation. See 51 Fed. Reg. 10510. Other physical or psychological abuse, serious neglect, and domestic violence in the home may also constitute an obvious grave risk to the child’s safety that could not readily be ameliorated. A court may also decline to consider imposing ameliorative measures where it reasonably expects that they will not be followed. See, e.g., Walsh v. Walsh, 221 F. 3d 204, 221 (CA1 2000) (providing example of parent with history of violating court orders).

“Second, consideration of ameliorative measures should abide by the Convention’s requirement that courts addressing return petitions do not usurp the role of the court that will adjudicate the underlying custody dispute. The Convention and ICARA prohibit courts from resolving any underlying custody dispute in adjudicating a return petition. See Art. 16, Treaty Doc., at 10; 22 U. S. C. §9001(b)(4). Accordingly, a court ordering ameliorative measures in making a return determination should limit those measures in time and scope to conditions that would permit safe return, without purporting to decide subsequent custody matters or weighing in on permanent arrangements.

“Third, any consideration of ameliorative measures must accord with the Convention’s requirement that courts “act expeditiously in proceedings for the return of children.” Art. 11, Treaty Doc., at 9. Timely resolution of return petitions is important in part because return is a “provisional” remedy to enable final custody determinations to proceed. Monasky, 589 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 3) (internal quotation marks omitted). The Convention also prioritizes expeditious determinations as being in the best interests of the child because “[e]xpedition will help minimize the extent to which uncertainty adds to the challenges confronting both parents and child.” Chafin v. Chafin, 568 U. S. 165, 180 (2013). A requirement to “examine the full range of options that might make possible the safe return of a child,” Blondin II, 238 F. 3d, at 163, n. 11, is in tension with this focus on expeditious resolution. In this case, for example, it took the District Court nine months to comply with the Second Circuit’s directive on remand. Remember, the Convention requires courts to resolve return petitions “us[ing] the most expeditious procedures available,” Art. 2, Treaty Doc., at 7, and to provide parties that request it with an explanation if proceedings extend longer than six weeks, Art. 11, id., at 9. Courts should structure return proceedings with these instructions in mind. Consideration of ameliorative measures should not cause undue delay in resolution of return petitions.

“To summarize, although nothing in the Convention prohibits a district court from considering ameliorative measures, and such consideration often may be appropriate, a district court reasonably may decline to consider ameliorative measures that have not been raised by the parties, are unworkable, draw the court into determinations properly resolved in custodial proceedings, or risk overly prolonging return proceedings. The court may also find the grave risk so unequivocal, or the potential harm so severe, that ameliorative measures would be inappropriate. Ultimately, a district court must exercise its discretion to consider ameliorative measures in a manner consistent with its general obligation to address the parties’ substantive arguments and its specific obligations under the Convention. A district court’s compliance with these requirements is subject to review under an ordinary abuse-of-discretion standard.”

News

Out Now: New open Access book on Children in Migration and International Family Law (Springer, 2024) by Stefan Arnold & Bettina Heiderhoff

Stefan Arnold (Institute of International Business Law, Chair for Private Law, Philosophy of Law, and Private International Law, University of Münster, Münster, Germany) and Bettina Heiderhoff (Institute for German and International Family Law, Chair for Private International Law, International Civil Procedure Law and German Private Law, University of Münster, Münster, Germany) have recently published an edited book on Children in Migration and International Family Law (Springer, 2024).

The book is an open access title, so it is freely available to all. In the editors’ words, the book aims “to shed light on the often overlooked legal difficulties at the interface between international family law and migration law” (p. 3) with focus placed “on the principle of the best interests of the child and how this principle can be more effectively applied.” (p.4)

The book’s blurb reads as follows:

This open access book offers readers a better understanding of the legal situation of children and families migrating to the EU. Shedding light on the legal, practical, and political difficulties at the intersection of international family law and migration law, it demonstrates that enhanced coordination between these policy areas is crucial to improving the legal situation of families on the move. It not only raises awareness of these “interface” issues and the need for stakeholders in migration law and international family law to collaborate closely, but also identifies deficits in the statutory framework and suggests possible remedies in the form of interpretation and regulatory measures.

This open access book offers readers a better understanding of the legal situation of children and families migrating to the EU. Shedding light on the legal, practical, and political difficulties at the intersection of international family law and migration law, it demonstrates that enhanced coordination between these policy areas is crucial to improving the legal situation of families on the move. It not only raises awareness of these “interface” issues and the need for stakeholders in migration law and international family law to collaborate closely, but also identifies deficits in the statutory framework and suggests possible remedies in the form of interpretation and regulatory measures.

The book is part of the EU co-financed FAMIMOVE project and includes contributions from international experts, who cover topics such as guardianship, early marriage, age assessment, and kafala from a truly European perspective. The authors’ approach involves a rigorous analysis of the relevant statutory framework, case law, and academic literature, with particular attention given to the best interest of the child in all its facets. The book examines how this principle can be more effectively applied and suggests ways to foster a more fruitful understanding of its regulatory potential.

Given its scope and focus, the book will be of interest to researchers, scholars, and practitioners of Private International Law, Family Law, and Migration Law. It makes a valuable contribution to these fields, particularly at their often-overlooked intersections.

The content of the chapters is succinctly summarized in the introductory chapter of the book, authored by the editors (“Children in Migration and International Family Law: An Introduction,” pp. 11–16). This summary is referenced here as a sort of abstract for each chapter. Read more

XVII Conference of the ASADIP: A More Intelligent and Less Artificial Private International Law

ASADIP: A More Intelligent and Less Artificial Private International Law

By Juan Ignacio Stampalija

The XVII Conference of the American Association of Private International Law (ASADIP) was held on September 25-27. Under the title ‘A More Intelligent and Less Artificial Private International Law,’ the main regional experts, as well as international guests, met at Universidad Austral of Argentina to discuss the main challenges of current private international law. Read more

English-language Master Program at Humboldt University Berlin

Humboldt University Berlin is launching an English-language LL.M. program!

The program will start in October 2025 and aims to attract graduates from all over the world with strong foundational knowledge in their respective legal system and at least one year of professional experience. Applications for the program will be possible from 1 to 31 March 2025.

More information is available on this flyer and online.

For any questions, please contact int.rewi@hu-berlin.de.