Views

The Data Protection Conflict: The EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016 and India’s Personal Data Protection Bill 2019

By Anubhav Das (National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi) and Aditi Jaiswal (Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow)

The internet brought significant changes in society, leading to a massive collection of data which necessitated legislation to regulate such data collection. The European Union enacted the General Data Protection Regulation, 2016(Hereafter GDPR), replacing the Data Protection Directive, 1995. Meanwhile, India, which currently lacks a separate data protection legislation, is in the process of enacting the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (Hereafter PDP). The PDP has been introduced in the Indian parliament and is currently under the scrutiny of a parliamentary committee. The primary purpose of these legislations is the protection of informational privacy.

Even though GDPR and PDP follow the same set of data protection principles, but, there exists an inevitable conflict between the two. This conflict determines the applicability of the legislation on the data subject. The territorial scope of GDPR and the PDP makes it clear that both overlap each other and this overlap can be used by companies involved in data processing or collection, to circumvent the civil liability arising under the laws. This post analyses the conflict between both the laws and in conclusion, it will suggest a way to overcome such an issue.

Territorial Scope: GDPR and PDP

Article 3 of the GDPR provides for the territorial applicability of the law. The Regulation applies to the processing of personal data by a controller or a processer. According to Article 3(1), any controller or processer that is established in the member state (European Union) shall fall under the scope of the GDPR. In other words, any company which has an office in the European Union shall come within the purview of the GDPR. Article 3(2) states that even if any processer or controller is not established in the European Union, but if they are offering goods or services irrespective of payment or monitoring behaviour in the European Union, then they will also fall under the scope of GDPR.

On the other hand, the PDP provides for the territorial applicability under Section 2. It applies to the processing of personal data by data fiduciary (similar to the controller under GDPR) and data processer (similar to processer under GDPR). Section 2(A) (a) states that if personal data is collected, disclosed, shared or otherwise processed within the territory of India, then it shall fall under the PDP. Section 2(A) (b), makes it applicable to the State, any Indian company, any citizen of India or any person or body of persons incorporated or created under Indian law. Section 2 (A) (c) makes it applicable to data fiduciary or data processor which are not in India but are processing in connection with any business carried on in India, or any systematic activity of offering goods or services to data principals within the territory of India or any activity concerning the profiling of data principle.

The Overlap of Jurisdiction

The internet has provided a way for companies to operate anywhere without the existence of an entity in a particular country. This also includes those companies which deal with data. In the context of Europe and India, a company doesn’t need to have an entity in Europe or India to operate and do business. Thus, an Indian company can easily do business related to data in Europe without any real existence in Europe and vice versa. Consequently, the problem that arises concerning data protection laws is complicated. An Indian company will fall under the purview of the PDP as per Section 2(A) (b) but at the same time if this Indian company also deals with ‘personal data for offering goods or services’ in the European Union, then it will also be regulated by the provisions of the GDPR.

Similarly, a European company ‘collecting data in India’ will fall under the scope of both PDP and GDPR. It is a matter of fact that judicial courts do not have jurisdiction over foreign land. Hence, no monetary damages can be imposed on companies which operate from Europe by using PDP or companies operating from India by using GDPR.

A European company or an Indian company can also claim that there is proper compliance with GDPR or PDP, respectively. In the context of Europe and India, a company only needs to follow the data protection law of the land from where it operates even though such an act violates data protection law of the other jurisdiction. This is possible as GDPR and PDP differ from each other on every key and essential aspect such as the very meaning of personal data.

The Difference and its Implications

The primary purpose of GDPR and PDP is the protection of personal data. But, the definition of personal data differs when GDPR is compared with PDP. The reason why such a description is essential is that a substantial part of both laws is based on the processing of personal data. This includes fair consent, purpose limitation, storage limitation, rights of data principle etc. Such aspects, when read with the territorial scope of both the laws, outlines the applicability of its provisions. The table below shows the difference in the definition of personal data.

| GDPR | PDP | |

|

Personal data is data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable, having regard to any characteristic, trait, attribute or any other feature of the identity of such natural person, whether online or offline, or any combination of such features with any additional information, and shall include any inference drawn from such data for profiling.

|

Note – Underlined are the parts which show that it is not present in the other law.

Both GDPR and PDP refer to personal data as information/data relating to identified/identifiable natural person. At the same time, the nuances of what constitutes an identifiable natural person differ significantly as both use different terminology which creates a diversion in the meaning of the personal data.

Deviation 1 – PDP provides for words such as ‘any other feature of identity, a combination of such feature with other information, any inference drawn for profiling’, in the meaning of an identifiable natural person. These terms can be interpreted more liberally and will probably be explained by courts in India and shall have an evolving meaning. GDPR, on the other hand, provides for specific terms like ‘physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, social identity’. Hence, European Courts will have to interpret personal data by mandatorily considering such terms, making it’s scope narrower when compared to PDP in this context.

Deviation 2 – Terms such as ‘identification number’ and ‘location data’ is mentioned explicitly in GDPR and not in PDP, making PDP narrower in scope here.

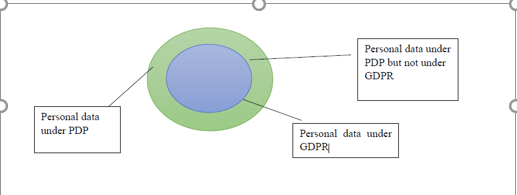

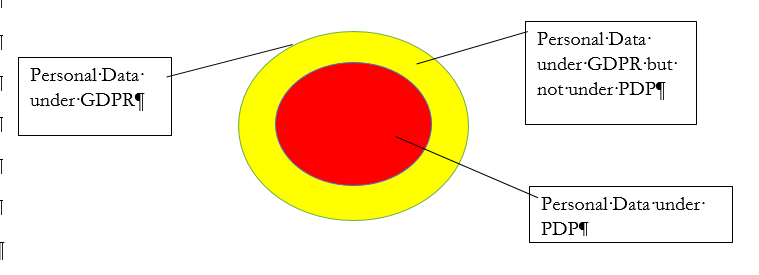

This above discussion can be easily understood with the help of the following figure –

Deviation 1 – The green circle represents inference in PDP. The blue circle represents inference in GDPR. The green stripe represents personal data which is covered in PDP and not covered in GDPR.

Deviation 2 – The yellow circle represents personal data in GDPR. The red circle represents personal data in PDP. The yellow stripe represents personal data which is covered in GDPR and not covered in PDP.

In the figure above, in Deviation 1, the green strip represents that personal data, which when processed by a company shall not fall under the scope of GDPR even though it shall be under the scope of the PDP. Such a difference implies that companies falling under the territorial ambit of both the laws, can follow one and circumvent the other.

A European company can process personal data represented in the green strip from India, and for that, it doesn’t need to comply with GDPR as that data is not personal data under GDPR. Now even though, there is a violation of the provisions under PDP the company can escape liability as Indian courts do not have jurisdiction in Europe, and European Courts cannot adjudge the matter as it falls outside the material scope of GDPR. The vice versa will happen if the case of deviation two is considered.

The consequence of such inconsistencies will be faced by data subjects who won’t be able to claim damages provided under their respective data protection law. One of the ways to ensure that damages can be claimed is by harmonising the data protection laws which can only be done by international cooperation.

The Need For International Cooperation in Data Protection

The existence of such issues in the framework of GDPR and PDP is not because of the extraterritorial application. Advocating against the extraterritorial application to resolve the problem of overlap in the jurisdiction of data protection laws would only give rise to more infringement of informational privacy of data subjects by foreign companies. This, in turn, will be detrimental for the very purpose for which data protection legislation is enacted.

The requirement at present is to harmonise the key definitions such as personal data in the data protection legislation. This will ensure that a right of action lies in both GDPR and PDP. Even if a foreign company cannot be dragged to the national court, harmonisation will at least ensure that a data subject has a right to seek damages in the international court.

The aspect discussed in this article is regarding two jurisdictions. However, consider, for instance, the complications that could arise when more than two jurisdictions are involved. To illustrate, an Indian Company having an office in Canada and that office is doing business in data from the European Union. In such cases, the best way to ensure data protection rights is by harmonisation, and this can only be achieved with the help of international cooperation. Thus, data protection in the age of internet needs multilateral international agreements.

Conclusion

The international regime of data protection is complicated in today’s world. There is no proper international agreement which governs the data protection legislation across the globe, which resulted in a difference in the critical terms of data protection when GDPR and PDP are compared. This, in – turn can be used by corporates to get away with liability. So, the aim must be not to let anyone violate the data protection principles by using this inconsistency and get away with it. To deal with this and safeguard the privacy of data subject, international cooperation in data protection is essential.

A Dangerous Chimera: Anti-Suit Injunctions Based on a “Right to be Sued” at the Place of Domicile under the Brussels Ia Regulation?

This post introduces my case note titled ‘A Dangerous Chimera: Anti-Suit Injunctions Based on a “Right to be Sued” at the Place of Domicile under the Brussels Ia Regulation?’ which appeared in the July 2020 issue of the Law Quarterly Review at page 379. An open access version of the case note is available here.

In Gray v Hurley [2019] EWCA Civ 2222, the Court of Appeal (Patten LJ, Hickinbottom LJ and Peter Jackson LJ), handed down the judgment on the claimant’s appeal in Gray v Hurley [2019] EWHC 1972 (QB). The appellant appealed against the refusal of an anti-suit injunction.

The appellant (Ms Gray) and respondent (Mr Hurley) had been in a relationship. They acquired property in various jurisdictions using the appellant’s money, but held it in either the respondent’s name or in corporate names. The relationship ended and a dispute commenced over ownership of some of the assets and properties. The appellant was domiciled in England; the respondent lived in New Zealand after the relationship ended and was no longer domiciled in England. He initiated proceedings there for a division of the property acquired by the couple during the relationship. The appellant issued proceedings in England seeking a declaration that she was entitled absolutely to the assets. She also applied for an anti-suit injunction to restrain the defendant from continuing with proceedings in the courts of New Zealand. Lavender J held that England was the appropriate forum for the trial of the appellant’s claims but that the respondent’s New Zealand claim could not be determined in England. He rejected her argument that Article 4(1) of the Brussels Ia Regulation obliged him to grant an anti-suit injunction to prevent the respondent from litigating against her in a non-EU state.

The appellant argued that Samengo-Turner v J&H Marsh & McLennan (Services) Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 723, [2007] 2 All E.R. (Comm) 813 and Petter v EMC Europe Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 828, [2015] C.P. Rep. 47 were binding authority that Article 4(1) provided her with a right not to be sued outside England, where she was domiciled, obliging the court to give effect to that right by granting an anti-suit injunction.

The Court of Appeal considered that the issue was not acte claire and sent a preliminary reference to the CJEU (pursuant to Article 267 TFEU) asking whether Article 4(1) of the Brussels Ia Regulation provided someone domiciled in England with a right not to be sued outside England so as to oblige the courts to give effect to that right by granting an anti-suit injunction.

The case note examines the Court of Appeal’s decision in Gray v Hurley [2019] EWCA Civ 2222. It offers a pervasive critique of the argument that the general rule of jurisdiction under the Brussels Ia Regulation gives rise to a substantive right to be sued only in England and that this right is capable of enforcement by an anti-suit injunction. It is argued that the previous decisions of the Court of Appeal in Samengo-Turner v J&H Marsh & McLennan (Services) Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 723 and Petter v EMC Europe Ltd [2015] EWCA Civ 828 were themselves wrongly decided. In light of this, it will be even more difficult to justify the broader application of a similar result in the present case.

Indeed, the law would take a wrong turn if the present case is allowed to build on the aberrational foundations of the developing law on anti-suit injunctions based on rights derived from the Brussels Ia Regulation. Essentially, a chimerical remedy based on a fictitious right would not only infringe comity but would also deny the respondent access to justice in the only available forum. The note also anticipates the CJEU’s potential findings in this case.

An open access version of the case note is available here.

Uber Arbitration Clause Unconscionable

In 2017 drivers working under contract for Uber in Ontario launched a class action. They alleged that under Ontario law they were employees entitled to various benefits Uber was not providing. In response, Uber sought to stay the proceedings on the basis of an arbitration clause in the standard-form contract with each driver. Under its terms a driver is required to resolve any dispute with Uber through mediation and arbitration in the Netherlands. The mediation and arbitration process requires up-front administrative and filing fees of US$14,500. In response, the drivers argued that the arbitration clause was unenforceable.

The Supreme Court of Canada has held in Uber Technologies Inc. v. Heller, 2020 SCC 16 that the arbitration clause is unenforceable, paving the way for the class action to proceed in Ontario. A majority of seven judges held the clause was unconscionable. One judge held that unconscionability was not the proper framework for analysis but that the clause was contrary to public policy. One judge, in dissent, upheld the clause.

A threshold dispute was whether the motion to stay the proceedings was under the Arbitration Act, 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 17 or the International Commercial Arbitration Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 2, Sch. 5. Eight judges held that as the dispute was fundamentally about labour and employment, the ICAA did not apply and the AA was the relevant statute (see paras. 18-28, 104). While s. 7(1) of the AA directs the court to stay proceedings in the face of an agreement to arbitration, s. 7(2) is an exception that applies, inter alia, if the arbitration agreement is “invalid”. That was accordingly the framework for the analysis. In dissent Justice Cote held that the ICAA was the applicable statute as the relationship was international and commercial in nature (paras. 210-18).

The majority (a decision written by Abella and Rowe JJ) offered two reasons for not leaving the issue of the validity of the clause to the arbitrator. First, although the issue involved a mixed question of law and fact, the question could be resolved by the court on only a “superficial review” of the record (para. 37). Second, the court was required to consider “whether there is a real prospect, in the circumstances, that the arbitrator may never decide the merits of the jurisdictional challenge” (para. 45). If so, the court is to decide the issue. This is rooted in concerns about access to justice (para. 38). In the majority’s view, the high fees required to commence the arbitration are a “brick wall” on any pathway to resolution of the drivers’ claims.

The majority then engaged in a detailed discussion of the doctrine of unconscionability. It requires both “an inequality of bargaining power and a resulting improvident bargain” (para. 65). On the former, the majority noted the standard form, take-it-or-leave-it nature of the contract and the “significant gulf in sophistication” between the parties (para. 93). On the latter, the majority stressed the high up-front costs and apparent necessity to travel to the Netherlands to raise any dispute (para. 94). In its view, “No reasonable person who had understood and appreciated the implications of the arbitration clause would have agreed to it” (para. 95). As a result, the clause is unconscionable and thus invalid.

Justice Brown instead relied on the public policy of favouring access to justice and precluding an ouster of the jurisdiction of the court. An arbitration clause that has the practical effect of precluding arbitration cannot be accepted (para. 119). Contractual stipulations that prohibit the resolution of disputes according to law, whether by express prohibition or simply by effect, are unenforceable as a matter of public policy (para. 121).

Justice Brown also set out at length his concerns about the majority’s reliance on unconscionability: “the doctrine of unconscionability is ill-suited here. Further, their approach is likely to introduce added uncertainty in the enforcement of contracts, where predictability is paramount” (para. 147). Indeed, he criticized the majority for significantly lowering the hurdle for unconscionability, suggesting that every standard-form contract would, on the majority’s view, meet the first element of an inequality of bargaining power and therefore open up an inquiry into the sufficiency of the bargain (paras. 162-63). Justice Brown concluded that “my colleagues’ approach drastically expands the scope of unconscionability, provides very little guidance for the doctrine’s application, and does all of this in the context of an appeal whose just disposition requires no such change” (para. 174).

In dissent, Justice Cote was critical of the other judges’ willingness, in the circumstances, to resolve the issue rather than refer it to the arbitrator for decision: “In my view, my colleagues’ efforts to avoid the operation of the rule of systematic referral to arbitration reflects the same historical hostility to arbitration which the legislature and this Court have sought to dispel. The simple fact is that the parties in this case have agreed to settle any disputes through arbitration; this Court should not hesitate to give effect to that arrangement. The ease with which my colleagues dispense with the Arbitration Clause on the basis of the thinnest of factual records causes me to fear that the doctrines of unconscionability and public policy are being converted into a form of ad hoc judicial moralism or “palm tree justice” that will sow uncertainty and invite endless litigation over the enforceability of arbitration agreements” (para. 237). Justice Cote also shared many of Justice Brown’s concerns about the majority’s use of unconscionability: “I am concerned that their threshold for a finding of inequality of bargaining power has been set so low as to be practically meaningless in the case of standard form contracts” (para. 257).

The decision is lengthy and several additional issues are canvassed, especially in the reasons of Justice Cote and Justice Brown. The ultimate result, with the drivers not being bound by the arbitration clause, is not that surprising. Perhaps the most significant questions moving forward will be the effect these reasons have on the doctrine of unconscionability more generally.

News

Out now: RabelsZ 88 (2024), Issue 1

The latest issue of RabelsZ has just been released. In addition to the following articles it contains fantastic news (mentioned in an earlier post today): Starting with this issue RabelsZ will be available open access! Enjoy reading:

The latest issue of RabelsZ has just been released. In addition to the following articles it contains fantastic news (mentioned in an earlier post today): Starting with this issue RabelsZ will be available open access! Enjoy reading:

Symeon C. Symeonides, The Torts Chapter of the Third Conflicts Restatement: An Introduction, pp. 7–59, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1628/rabelsz-2024-0001 Read more

Rabels Zeitschrift Open Access

Since the beginning of this year, Rabels Zeitschrift is available in open access. For a long time, the journal has published articles in other languages than German in particular English. The new open access model should make it even more attractive for authors wishing to reach an international audience. And it enables readers from places without a subscription – not only, but also in the Global South – to have access to scholarship. What follows is a translation of the Editorial in Rabels Zeitschrift, Volume 88 (2024) / Issue 1, pp. 1-4: Open Access – was sich mit diesem Heft ändert by Holger Fleischer, Ralf Michaels, Anne Röthel, Christian Eckl, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Translation by Michael Friedman.

HCCH Monthly Update: March 2024

Conventions & Instruments

On 14 March 2024, Angola deposited its instrument of accession to the 1993 Adoption Convention. With the accession of Angola, the 1993 Adoption Convention now has 106 Contracting Parties. More information is available here.

On 14 March 2024, Moldova deposited its instrument of accession to the 2005 Choice of Court Convention. With the accession of Moldova, 33 States and the European Union are bound by the 2005 Choice of Court Convention. More information is available here.

On 21 March 2024, El Salvador deposited its instrument of accession to the 1965 Service Convention and the Dominican Republic deposited its instruments of accession to the 1965 Service Convention and the 2007 Child Support Convention. More information is available here.

Meetings & Events

From 5 to 8 March 2024, the Council on General Affairs and Policy (CGAP) of the HCCH met in The Hague, with over 429 participants joining both in person and online. HCCH Members reviewed progress made to date and agreed on the work programme for the year ahead in terms of normative, non-normative and governance work. More information is available here.

On 22 March 2024, the Permanent Bureau hosted the webinar “HCCH 2005 Choice of Court Convention: Fostering Access to Justice for Cross-Border Commerce in the Asia Pacific Region”.

Publications

On 8 March 2023, the Permanent Bureau announced the publication of the HCCH 2023 Annual Report. More information is available here.

These monthly updates are published by the Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH), providing an overview of the latest developments. More information and materials are available on the HCCH website.