Views

Choice of law rules and statutory interpretation in the Ruby Princess Case in Australia

Written by Seung Chan Rhee and Alan Zheng

Suppose a company sells tickets for cruises to/from Australia. The passengers hail from Australia, and other countries. The contracts contain an exclusive foreign jurisdiction clause nominating a non-Australian jurisdiction. The company is incorporated in Bermuda. Cruises are only temporarily in Australian territorial waters.

German Federal Court of Justice: Article 26 Brussels Ia Regulation Applies to Non-EU Defendants

By Moses Wiepen, Legal Trainee at the Higher Regional Court of Hamm, Germany

In its decision of 21 July 2023 (V ZR 112/22), the German Federal Court of Justice confirmed that Art. 26 Brussels Ia Regulation applies regardless of the defendant’s domicile. The case in question involved an art collector filing suit against a Canadian trust that manages the estate of a Jew who was persecuted by the German Nazi regime. The defendant published a wanted notice in an online Lost Art database for a painting that the plaintiff bought in 1999. The plaintiff considers this as a violation of his property right.

This week begins the Special Commission on the 1980 Child Abduction Convention and the 1996 Child Protection Convention

Written by Mayela Celis

The eighth meeting of the Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the 1980 Child Abduction Convention and the 1996 Child Protection Convention will be held from 10 to 17 October 2023 in The Hague, the Netherlands. For more information, click here.

One of the key documents prepared for the meeting is the Global Report – Statistical study of applications made in 2021 under the 1980 Child Abduction Convention, where crucial information has been gathered about the application of this Convention during the year 2021. However, these figures were perhaps affected by the Covid-19 pandemic as indicated in the Addendum of the document (see paragraphs 157-167, pp. 33-34). Because it refers to a time period in the midst of lockdowns and travel restrictions, it is not unrealistic to say that the figures of the year 2021 should be taken with a grain of salt. For example, the overall return rate was the lowest ever recorded at 39% (it was 45% in 2015). The percentage of the combined sole and multiple reasons for judicial refusals in 2021 was 46% as regards the grave risk exception (it was 25% in 2015). The overall average time taken to reach a final outcome from the receipt of the application by the Central Authority in 2021 was 207 days (it was 164 days in 2015). While statistics are always useful to understand a social phenomenon, one may only wonder why a statistical study was conducted with regard to applications during such an unusual year – apart from the fact that a Special Commission meeting is taking place and needs recent statistics -, as it will unlikely reflect realistic trends (but it can certainly satisfy a curious mind).

News

PIL conference in Ljubljana, 18 September 2025

University of Ljubljana is organising Private International Law Conference with sessions in Slovenian and English. The conference, which will take place in Ljubljana (Slovenia) on 18 September 2025, will gather reknown academics and practitioners who will address current topics in European and international PIL.

The programme is available by clicking here: PIL-Ljubljana2025 and for more infromation you are welcome to contact the organisers at: ipp.pf@pf.uni-lj.si.

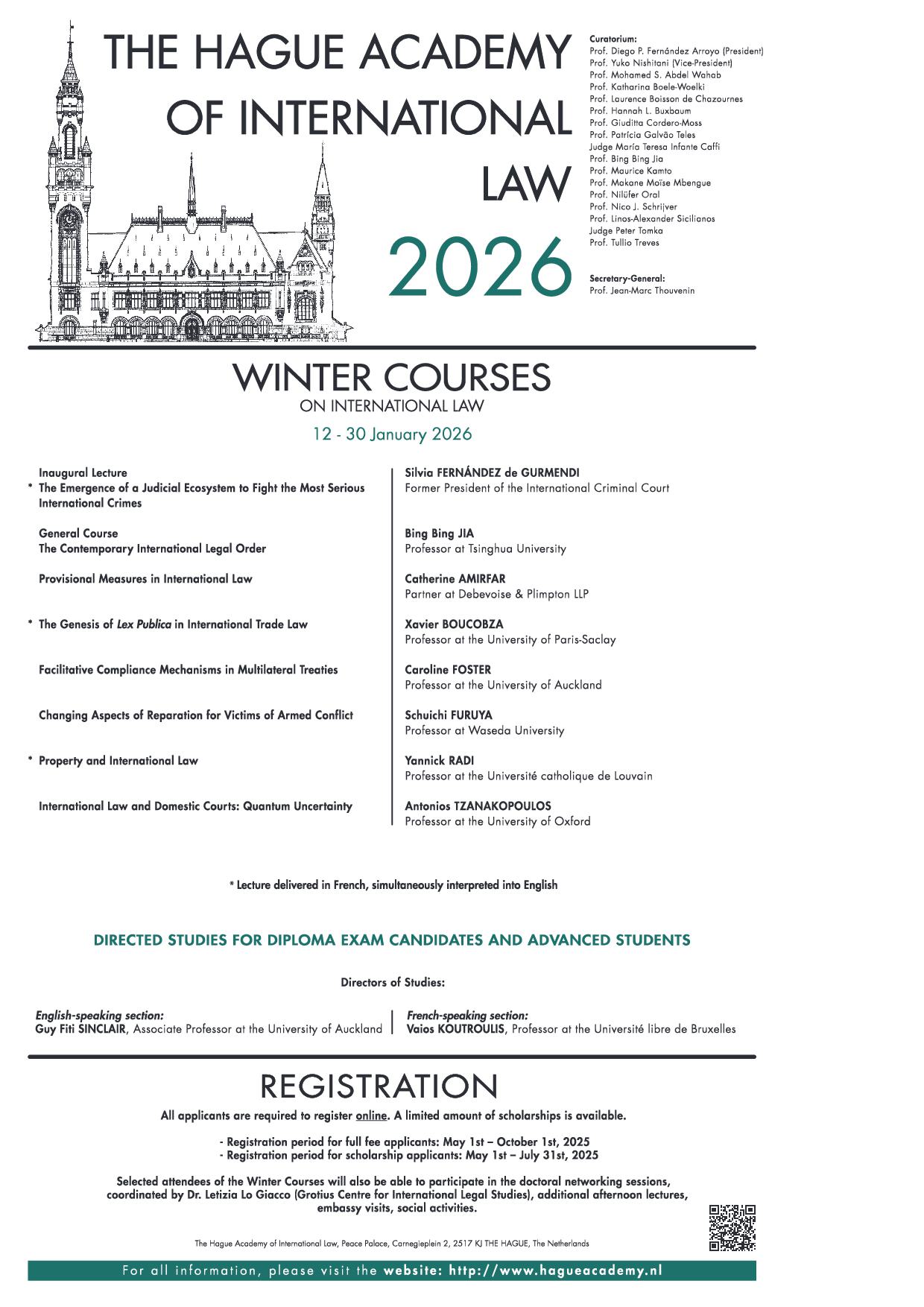

Registration Open Soon: The Hague Academy of International Law’s Winter Courses 2026

Recently, the Hague Academy of International Law published the 2026 programme of its renowned Winter Courses in International Law (12-30 January 2026). Unlike the Summer Courses, this program presents lectures on both Public and Private International Law and therefore provides for a particularly holistic academic experience. Once again, the Academy has spared no effort in inviting legal scholars from around the world to The Hague, including speakers from countries as diverse as Argentina, Belgium, China, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, offering its audience a truly global perspective on the topic. Read more

1st Issue of Journal of Private International Law for 2025

The first issue of the Journal of Private International Law for 2025 was published today. It contains the following articles:

Pietro Franzina, Cristina González Beilfuss, Jan von Hein, Katja Karjalainen & Thalia Kruger, “Cross-border protection of adults: what could the EU do better?†”

On 31 May 2023 the European Commission published two proposals on the protection of adults. The first proposal is for a Council Decision to authorise Member States to become or remain parties to the Hague Adults Convention “in the interest of the European Union.” The second is a proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council which would supplement (and depart from, in some respects) the Convention’s rules. The aim of the proposals is to ensure that the protection of adults is maintained in cross-border cases, and that their right to individual autonomy, including the freedom to make their own choices as regards their person and property is respected when they move from one State to another or, more generally, when their interests are at stake in two or more jurisdictions. This paper analyses these EU proposals, in particular as regards the Regulation, and suggests potential improvements.