Views

Pilar Jiménez Blanco on Cross-Border Matrimonial Property Regimes

Written by Pilar Jiménez Blanco about her book:

Pilar Jiménez Blanco, Regímenes económicos matrimoniales transfronterizos [Un estudio del Reglamento (UE) nº 2016/1103], Tirant lo Blanch, 2021, 407 p., ISBN 978-84-1355-876-9

The Regulation (EU) No 2016/1103 is the reference Regulation in matters of cross-border matrimonial property regimes. This book carries out an exhaustive analysis of the Regulation, overcoming its complexity and technical difficulties.

The book is divided in two parts. The first is related to the applicable law, including the legal matrimonial regime and the matrimonial property agreement and the scope of the applicable law. The second part is related to litigation, including the rules of jurisdiction and the system for the recognition of decisions. The study of the jurisdiction rules is ordered according to the type of litigation and the moment in which it arises, depending on whether the marriage is in force or has been dissolved by divorce or death. Three guiding principles of the Regulation are identified: 1) The need of coordination with the EU Regulations on family matters (divorce and maintenance) and succession. This coordination can be achieved through the choice of law by the spouses to ensure the application of the same law to divorce, to the liquidation of the matrimonial regime, to maintenance and even to agreements as to succession. In addition, a broad interpretation of “maintenance” that includes figures such as compensatory pension (known, for example, in Spanish law) allows that one of the spouses objects to the application of the law of the habitual residence of the creditor and the law of another State has a closer connection with the marriage, based on art. 5 of the 2007 Hague Protocol. In such a case, the governing law of the matrimonial property regime could be considered as the closest law.

In the field of international jurisdiction, the coordination between EU Regulations is intended to be ensured with exclusive jurisdiction by ancillary linked to succession proceedings or linked to matrimonial proceedings pending before the courts of other Member States. Although the ancillary jurisdiction of the proceedings on the matrimonial property regime with respect to maintenance claims is not foreseen, the possibility of accumulation of these claims is possible through a choice of court to the competent court to matrimonial matters.

2) The unitary treatment of the matrimonial property regime. The general rule is that only one law is applicable and only one court is competent to matrimonial property regimes, regardless of the location of the assets. The exceptions derived from the registry rules of the real estate situation and the effect to third parties are analysed.

3) The legal certainty and predictability. The general criterion is the immutability and stability of the matrimonial property regime, so that the connections are fixed at the beginning of married life and mobile conflict does not operate, as a rule. The changes allowed will always be without opposition from any spouse and safe from the rights of third parties. The commitment to legal certainty and predictability of the matrimonial property regime governing law prevails over the proximity current relationship of the spouses with another State law.

Related to applicable law, the following contents can be highlighted:

-The importance of choosing the governing law of the matrimonial property regime. The choice of law has undoubted advantages for the spouses to coordinate the law applicable to the matrimonial property regime with the competent courts and with the governing law of related issues related to divorce, maintenance and succession law. The choice of law is especially recommended if matrimonial property agreements are granted in case of spouses’ different nationalities and different habitual residence, since it avoids uncertainty in determining the law of the closest connection established in art. 26.1.c). Of particular importance is the question of form and consent in the choice of law, given the ambiguity of the Regulation on the need for this consent to be express.

-The interest in conclude matrimonial property agreements and, specially, the prenuptial agreements. Its initial validity requires checking the content of each agreement to verify which is the applicable law and which is included within the scope of the Regulation (EU) No 2016/1103. The enforceability of these agreements poses problems when new unforeseeable circumstances have appeared for the spouses, which will require an assessment of the effectiveness of the agreements in a global manner – not fragmented according to each agreement – to verify the minimum necessary protection of each spouse.

-The singularities of the scope of application of the governing matrimonial property regime law. The issues included in the governing law require prior consultation with said law to identify any specialty in the matrimonial property regime relations between the spouses or in relation to third parties. This has consequences related to special capacity rules to conclude matrimonial property agreements, limitations to dispose of certain assets, limitations for contracts between spouses or with respect to third parties or the relationship between the matrimonial property regimes and the civil liability of the spouses. Of particular importance is the regime of the family home, which is analysed from the perspective of the limitations for its disposal and from the perspective of the rules of assignment of use to one of the spouses.

-The balance between the protection of spouses and the protection of third parties. From art. 28 of the Regulation, derives the recommendation for the spouses to register their matrimonial property regime, whenever possible, in the registry of their residence and in the property registry of the real estate situation. The recommendation for third parties is to consult the matrimonial property regime in the registries of their residence and real estate. As an alternative, it is recommended to choose – as the governing law of the contract – the same law that governs the matrimonial property regime.

– The effects on the registries law. Although the registration of rights falls outside the scope of the Regulation, for the purposes of guaranteeing correct publicity in the registry of the matrimonial property regimes of foreign spouses, it would be advisable to eventually adapt the registry law of the Member States to the Regulation (EU) No 2016/1103. A solution consistent with the Regulation would be to allow the matrimonial property regime registry access when the first habitual residence of the couple is established in that State.

Related to jurisdiction, the following contents can be highlighted:

-The keys of the rules of jurisdiction. The rules of jurisdiction only regulate international jurisdiction, respecting the organization of jurisdiction among the “courts” within each State. It will be the procedural rules of the Member States that determine the type of intervening authority (judicial or notarial), as well as the territorial and functional jurisdiction.

The rules of jurisdiction are classified into two groups: 1) litigation with a marriage in force, referred to in the general forums of arts. 6 et seq.); 2) litigation in case of dissolution of the marriage, due to death or marital crisis. These are subject to two types of rules: if the link (spatial, temporal and material) with the divorce or succession court is fulfilled, this court has exclusive jurisdiction, in accordance with arts. 4 and 5; failing that, it goes back to the general forums of the Regulation.

Jurisdiction related to succession proceedings (based on art. 4) poses a problem of lack of proximity of the court with the surviving spouse, especially when the criterion of jurisdiction for the succession established by Regulation (EU) No 650/2012 has little connection with that State. This will be the case especially when the jurisdiction for succession is based on the location of an asset in that State (art. 10.2) or on the forum necessitatis (art. 11).

Jurisdiction related to matrimonial proceedings (based on art. 5) poses some problems such as the one derived from a lack of temporary fixation of the incidental nature. The problem is to determine how long this court has jurisdiction.

-The interest of the choice of court. The choice of court is especially useful to reinforce the choice of law. Submission may also be convenient, especially to the State of the celebration, for marriages that are at risk of not being recognized in any Member State by virtue of art. 9 (for example, same-sex marriages).

The inclusion of a submission in a prenuptial agreement or in a matrimonial property agreement does not avoid the uncertainty of the competent court. There is a clear preference for the concentration of the jurisdiction of arts. 4 and 5 apart from the pact of submission made between the spouses. In any case, the choice of court can be operative if the proceedings on the matrimonial issue has been raised before courts with the minimum connection referred to in art. 5.2.

Problems arise due to the dependence of the jurisdiction on the applicable law established in art. 22 of the Regulation, since it requires anticipating the determination of the law applicable to the matrimonial property regime in order to control international jurisdiction.

Related to recognition, the following contents can be highlighted:

-The delimitation between court decision and authentic instrument does not depend on the intervening authority – judicial or notarial –, but on the exercise of the jurisdictional function, which implies the exercise of a decision-making activity by the intervening authority. This allows notarial divorces to be included and notoriety acts of the matrimonial property regime to be excluded.

The recognition system follows the classic model of the European Regulations, taking as a reference the Regulation (EU) No 650/2012 on succession. Therefore, the need for exequatur to enforceability of court decisions is maintained.

The obligation to apply the grounds for refusal of recognition with respect to the fundamental rights recognised in the EU Charter and, in particular, in art. 21 thereof on the principle of non-discrimination. This supposes an express incorporation of the European public policy to the normative body of a Regulation. Specially, the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation means the impossibility of using the public policy ground to deny recognition of a decision issued by the courts of another Member State relative to the matrimonial property regime of a marriage between spouses of the same sex.

The study merges the rigorous interpretation of EU rules with practical reality and includes case examples for each problem area. The book is completed with many references on comparative law, which show the different systems for dealing with matters of the matrimonial property regime applied in the Member States. It is, therefore, an essential reference book for judges, notaries, lawyers or any other professional who performs legal advice in matrimonial affairs.

Are the Chapter 2 General Protections in the Australian Consumer Law Mandatory Laws?

Neerav Srivastava, a Ph.D. candidate at Monash University offers an analysis on whether the Chapter 2 general protections in the Australia’s Competition and Consumer Act 2010 are mandatory laws.

Online Australian consumer transactions on multinational platforms have grown rapidly. Online Australian consumers contract typically include exclusive jurisdiction clauses (EJC) and foreign choice of law clauses (FCL). The EJC and FCL, respectively, are often in favour of a US jurisdiction. Particularly when an Australian consumer is involved, the EJC might be void or an Australian court may refuse to enforce it.[1] And the ‘consumer guarantees’ in Chap 3 of the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’) are explicitly ‘mandatory laws’[2] that the contract cannot exclude. It is less clear whether the general protections at Chap 2 of the ACL are non-excludable. Unlike the consumer guarantees, it is not stated that the Chap 2 protections are mandatory. As Davies et al and Douglas[3] rightly point out that may imply they are not mandatory. In ‘Indie Law For Youtubers: Youtube And The Legality Of Demonetisation’ (2021) 42 Adelaide Law Review503, I argue that the Chap 2 protections are mandatory laws.

The Chap 2 protections, which are not limited to consumers, are against:

- misleading or deceptive conduct under s 18

- unconscionable conduct under s 21

- unfair contract terms under s 23

I. PRACTICALLY SIGNIFICANT

If the Chap 2 protections are mandatory laws, that is practically significant. Australian consumers and others can rely on the protections, and multinational platforms need to calibrate their approach accordingly. Australia places a greater emphasis on consumer protection,[4] whereas the US gives primacy to freedom of contract.[5] Part 2 may give a different answer to US law. For example, the YouTube business model is built on advertising revenue generated from content uploaded by YouTubers. Under the YouTube contract, advertising revenue is split between a YouTuber (55%) and YouTube (45%). When a YouTuber does not meet the minimum threshold hours, or YouTube deems content as inappropriate, a YouTuber cannot monetise that content. This is known as demonetisation. On the assumption that the Chap 2 protections apply, the article argues that

- not providing reasons to a Youtuber for demonetisation is unconscionable

- in the US, it has been held that clauses that allow YouTube to unilaterally vary its terms, eg changing its demonetisation policy, are enforceable. Under Chap 2 of the ACL, such a clause is probably void.

If that is correct, it is relevant to Australian YouTubers. It may also affect the tactical landscape globally regarding the demonetisation dispute.

II. WHETHER MANDATORY

As to why the Chap 2 protections are mandatory laws, first, the ACL does not state that they are not mandatory. The Chap 2 protections have been characterised as rights that cannot be excluded.[6]

The objects of the ACL, namely to enhance the welfare of Australians and consumer protection, suggest[7] that Chap 2 is mandatory. A FCL, sometimes combined with an EJC, may alienate Australian consumers, the weaker party, from legal remedies.[8] Allowing this to proliferate would be inconsistent with the ACL’s objects. If Chap 2 is not mandatory, all businesses — Australian and international — could start using FCLs to avoid Chap 2 and render it otiose.

Further there is a public dimension to the Chap 2 protections,[9] in that they are subject to regulatory enforcement. It can be ordered that pecuniary penalties be paid to the government and compensation be awarded to non-parties. In this respect, Chap 3 is similar to criminal laws, which are generally understood to have a strict territorial application.[10]

As for policy being ‘particularly’ important where there is an inequality of bargaining power, both ss 21[11] and 23 are specifically directed at redressing inequality.[12]

Regarding the specific provisions:

- Authority on, at least, s 18 suggests that it is mandatory.[13]

- Section 21 on unconscionable conduct has been held to be a mandatory law, although that conclusion was not a detailed judicial consideration.[14] In any event, it is arguable that ‘conduct’ is broader than a contract, and parties cannot exclude ‘conduct’ provisions.[15] Unconscionability is determined by reference to ‘norms’ of Australian society and is, therefore, not an issue exclusively between the parties.[16]

- Whether s 23 on unfair contract terms is a mandatory law is debatable.[17] At common law, the proper law governs all aspects of a contractual obligation, including its validity. The counterargument is that s 23 is a statutory regime that supersedes the common law. As a matter of policy, Australia is one of the few jurisdictions to extend unfair terms protection to small businesses expressly, for example, a YouTuber. An interpretation that s 23 can be disapplied by a FCL would be problematic. A FCL designed to evade the operation of ss 21 or 23 might itself be unconscionable or unfair.[18] If s 23 is not mandatory, Australian consumers may not have the benefit of an important protection. Section 23 also has a public interest element, in that under s 250 the regulator can apply to have a term declared unfair. On balance, it is more likely than not that s 21 is a mandatory law.

The Chap 2 protections are an integral part of the Australian legal landscape and the market culture. This piece argues that the Chap 2 protections are mandatory laws. Whether or not that is correct, as a matter of policy, they should be.

FOOTNOTES

[1] A possibility implicitly left open by Epic Games Inc v Apple Inc [2021] FCA 338, [17]. See too Knight v Adventure Associates Pty Ltd [1999] NSWSC 861, [32]–[36] (Master Malpass); Quinlan v Safe International Försäkrings AB [2005] FCA 1362, [46] (Nicholson J), Home Ice Cream Pty Ltd v McNabb Technologies LLC [2018] FCA 1033, [19].

[2] ‘laws the respect for which is regarded by a country as so crucial for safeguarding public interests (political, social, or economic organization) that they are applicable to any contract falling within their scope, regardless of the law which might otherwise be applied’. See Adrian Briggs, The Conflict of Laws (Oxford University Press, 3rd ed, 2013) 248.

[3] M Davies et al, Nygh’s Conflict of Laws in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 10th ed, 2019) 492 [19.48], Michael Douglas, ‘Choice of Law in the Age of Statutes: A Defence of Statutory Interpretation After Valve’ in Michael Douglas et al (eds), Commercial Issues in Private International Law: A Common Law Perspective (Hart Publishing, 2019) 201, 226-7.

[4] Richard Garnett, ‘Arbitration of Cross-Border Consumer Transactions in Australia: A Way Forward?’ (2017) 39(4) Sydney Law Review 569, 570, 599.

[5] Sweet v Google Inc (ND Cal, Case No 17-cv-03953-EMC, 7 March 2018).

[6] Home Ice Cream Pty Ltd v McNabb Technologies LLC [2018] FCA 1033, [19].

[7] M Davies et al, Nygh’s Conflict of Laws in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 10th ed, 2019) 470–2 [19.10].

[8] See, eg, Océano Grupo Editorial SA v Murciano Quintero (C-240/98) [2000] ECR I-4963.

[9] Epic Games Inc v Apple Inc (2021) 392 ALR 66, 72 [23] (Middleton, Jagot and Moshinsky JJ).

[10] John Goldring, ‘Globalisation and Consumer Protection Laws’ (2008) 8(1) Macquarie Law Journal 79, 87-8

[11] Historically, the essence of unconscionability is the exploitation of a weaker party. Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt (2019) 267 CLR 1, 36 [81] (Gageler J) (‘ASIC v Kobelt’).

[12] M Davies et al, Nygh’s Conflict of Laws in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 10th ed, 2019) 470–2 [19.10], 492 [19.48].

[13] Home Ice Cream Pty Ltd v McNabb Technologies LLC [2018] FCA 1033, [19].

[14] Epic Games Inc v Apple Inc [2021] FCA 338, [19] (Perram J). On appeal, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia exercised its discretion afresh and refused the stay: Epic Games Inc v Apple Inc (2021) 392 ALR 66. That said, Perram J’s conclusion that s 21 was a mandatory law was not challenged on appeal.

[15] Analogical support for a ‘conduct’ analysis can be found from cases on s 18 like Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation [No 3] (2016) 337 ALR 647 (Edelman J, at first instance). In Valve it was reiterated that the test for s 18 was objective. See 689 [212]–[213]. A contractual term might neutralise the misleading or deceptive conduct, but it cannot be contracted out of. See Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1, 17 [37] (Stone J, Moore J agreeing at 4 [1], Mansfield J agreeing at 11 [17]); Downey v Carlson Hotels Asia Pacific Pty Ltd [2005] QCA 199, 29–30 [83] (Keane JA, Williams JA agreeing at [1], Atkinson J agreeing at [145]).

[16] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) [No 2] [2017] FCA 709, [60]–[62] (Beach J).

[17] M Davies et al, Nygh’s Conflict of Laws in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 10th ed, 2019) 463 [19.1], 492 [19.48].

[18] M Davies et al, Nygh’s Conflict of Laws in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 10th ed, 2019) 470–2 [19.10]. While a consumer might be able to challenge a proper law of contract clause on the grounds of unconscionability, it would be harder for a commercial party to do so.

A Boost in the Number of European Small Claims Procedures before Spanish Courts: A Collateral Effect of the Massive Number of Applications for European Payment Orders?

Carlos Santaló Goris, Researcher at the Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Luxembourg, offers an analysis of the Spanish statistics on the European Small Claims Procedure.

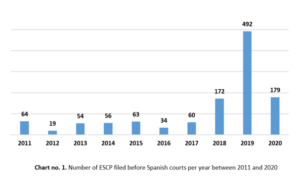

Until 2017, the annual number of European Small Claims Proceedings (“ESCP”) in Spain was relatively small, with an average of 50 ESCPs per year. With some exceptions, this minimal use of the ESCP fits the general trend across Europe (Deloitte Report). However, from 2017 to 2018 the number of ESCPs in Spain increased 286,6%. Against the 60 ESCPs issued in 2017, 172 were issued in 2020. In 2019, the number of ESCPs continued climbing to 492 ESCPs. This trend reversed in 2020, when there were just 179 ESCPs.

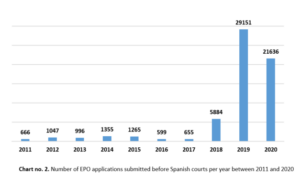

The use of the Regulation establishing the European Payment Order (“EPO Regulation”) experienced a similar fluctuation between 2018 and 2020. Since its entry into force, the EPO Regulation was significantly more prevalent among Spanish creditors than the ESCP Regulation. Between 2011 to 2020, there were an average of 940 EPO applications per year. Nonetheless, from 2017 to 2019, the number of EPO applications increased 4.451%: just in 2019, 29,151 EPOs were issued in Spain. In 2020, the number of EPOs decreased to 21,636. the massive boost in EPO applications results from creditors’ attempts to circumvent EU consumer protection standards under the Spanish domestic payment order.

From Banco Español de Crédito to Bondora

After the CJEU judgment C-618/10, Banco Español de Crédito, the Spanish legislator amended the Spanish Code of Civil Procedure to impose on courts a mandatory review of the fairness of the contractual terms in a request for a domestic payment order. Creditors noticed that they could circumvent such control through the EPO. Unlike the Spanish payment order, the EPO is a non-documentary type payment order. For an EPO, standard form creditors only have to indicate “the cause of the action, including a description of the circumstances invoked as the basis of the claim” as well as “a description of evidence supporting the claim” (Article 7(2) EPO Regulation). Moreover, the Spanish legislation implementing the EPO states that courts have to reject any other documentation beyond the EPO application standard form. Creditors realized that in this manner there was no possible way for the court to examine the fairness of the contratual terms in EPOs against consumers. Consequently, the number of EPO applications between 2017 and 2019 increased remarkably.

In some cases, a claim’s cross-border dimension was even fabricated to access the EPO Regulation. The EPO, like the ESCP, is only applicable in cross-border claims, which means that “at least one of the parties is domiciled or habitually resident in a Member State other than the Member State of the court seised”(Article 3 EPO Regulation). Against this background, creditors assigned the debt to a creditor abroad (in many cases, vulture funds and companies specialized in debt recovery) in order to transform a purely internal claim into a cross-border one.

The abnormal increase in the number of EPOs did not go unnoticed among Spanish judges. Three Spanish courts decided to submit preliminary references to the CJEU, asking, precisely, whether it is possible to examine the fairness of the contractual terms in an EPO application requested against a consumer. Two of these preliminary references led to the judgment Joined Cases C?453/18 and C?494/18, Bondora, where the CJEU replied positively, acknowledging that courts can examine the fairness of the contractual terms (on this judgment, see this previous post). The judgment was rendered in December 2019. In 2020, the number of EPOs started to decrease. It appears that after Bondora the EPO became less attractive to creditors.

The connection between the EPO and the ESCP Regulation

At this point one needs to ask how the increase in the use of the EPO Regulation has had an impact on the use of the ESCP Regulation. The answer is likely found in the 2015 joint reform of the EPO and ESCP Regulations (Regulation (EU) 2015/2421). Among other changes, this reform introduced an amendment in the EPO Regulation which allows, once the creditor lodges a statement of opposition against an EPO, for an automatic continuation of proceedings under the ESCP (Article 17(1)(a) EPO Regulation). For this to happen, creditors simply need to state their intention by making use of a code in the EPO application standard form. It appears that, in Spain, many of those creditors who applied for an EPO in order to circumvent consumer protection standards under the domestic payment order found in the ESCP a subsdiary proceeding if debtors opposed the EPO.

An isolated Spanish phenomenon?

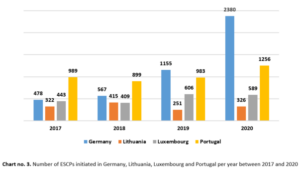

Statistics in Spain show that, at least in this Member State, the connection between the EPO and ESCP Regulations functions and gives more visibility to the ESCP. The lack of awareness about the ESCP Regulation was one of the issues that the Commission aimed to tackle with the 2015 reform. One might wonder if a similar increase in the use of the ESCP could be appreciated in other Member States. Available public statistics in Portugal, Lithuania, and Luxembourg do not reveal any significant change in the use of the ESCP after 2017, the year the amendment entered into force. In Lithuania, the number of ESCPs even decreased from 2018 to 2019.

Conversely, in Germany, statistics reveal a steady growth over those years. Against the 478 ESCPs issued in Germany in 2017, 2380 ESCP were issued in 2020, standing for an increase of 498%. Perhaps, after an unsuccessful start, the ESCP Regulation is finally bearing fruit.

News

Two Positions for Doctoral Students at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany

The Department ‘Law & Anthropology ’ of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany, is offering positions in the Max Planck Research Group ‘Transformations in Private Law: Culture, Climate, and

Technology’ headed by Mareike Schmidt for two doctoral students with projects on Cultural Embeddedness of Private Law.

The full advertisement can be found here.

ZEuP – Zeitschrift für Europäisches Privatrecht 4/2024

A new issue of ZEuP – Zeitschrift für Europäisches Privatrecht is now available and includes contributions on EU private law, comparative law and legal history, legal unification, private international law, and individual European private law regimes. The full table of content can be accessed here.

The following contributions might be of particular interest for the readers of this blog: Read more