Views

Red-chip enterprises’ overseas listing: Securities regulation and conflict of laws

Written by Jingru Wang, Wuhan University Institute of International Law

1.Background

Three days after its low-key listing in the US on 30 June 2021, Didi Chuxing (hereinafter “Didi”) was investigated by the Cyberspace Administration of China (hereinafter “CAC”) based on the Chinese National Security Law and Measures for Cybersecurity Review.[1] Didi Chuxing as well as 25 Didi-related APPs were then banned for seriously violating laws around collecting and using personal information,[2] leading to the plummet of Didi’s share. On 16 July 2021, the CAC, along with other six government authorities, began an on-site cybersecurity inspection of Didi.[3] The CAC swiftly issued the draft rules of Measures for Cybersecurity Review and opened for public consultation.[4] It proposed that any company with data of more than one million users must seek the Office of Cybersecurity Review’s approval before listing its shares overseas. It also proposed companies must submit IPO materials to the Office of Cybersecurity Review for review ahead of listing.

It is a touchy subject. Didi Chuxing is a Beijing-based vehicle for hire company. Its core business bases on the accumulation of mass data which include personal and traffic information. The accumulated data not only forms Didi’s unique advantage but also is the focus of supervision. The real concern lays in the possible disclosure of relevant operational and financial information at the request of US securities laws and regulations, which may cause data leakage and threaten national security. Therefore, China is much alert to information-based companies trying to list overseas.

The overseas listing of China-related companies has triggered regulatory conflicts long ago. The Didi event only shows the tip of an iceberg. This note will focus on two issues: (1) China’s supervision of red-chip companies’ overseas listing; (2) the conflicts between the US’s demand for disclosure and China’s refusal against the US’s extraterritorial jurisdiction.

2. Chinese supervision on red-chip companies’ overseas listing

A red-chip company does most of its business in China, while it is incorporated outside mainland China and listed on the foreign stock exchange (such as New York Stock Exchange). Therefore, it is expected to maintain the filing and reporting requirements of the foreign exchange. This makes them an important outlet for foreign investors who wish to participate in the rapid growth of the Chinese economy. When asking Chinese supervision on red-chip companies listed overseas, such as Didi, the foremost question is whether the Chinese regulatory authority’s approval is required for them to launch their shares overseas. It is uneasy to conclude.

One reference is the Chinese Securities Law. Article 238 of the original version of the Chinese Securities Law provides that “domestic enterprises issuing securities overseas directly or indirectly or listing their securities overseas shall obtain approval from the securities regulatory authority of the State Council following the relevant provisions of the State Council.” This provision was amended in 2019. The current version (Art. 224 of the Chinese Securities Law) only requires the domestic enterprises to comply with the relevant provisions of the State Council. The amendment indicated that China has adopted a more flexible approach to addressing overseas listing. Literally, the securities regulatory authority’s approval is no longer a prerequisite for domestic enterprises to issue securities overseas.

When it comes to Didi’s listing in the US, a preliminary question is the applicability of such provision. Art. 224 is applied to “domestic enterprise” only. China adopts the doctrine of incorporation to ascertain company’s nationality.[5] According to Article 191 of the Chinese Company Law, companies established outside China under the provisions of foreign law are regarded as foreign companies. Didi Global Inc. is incorporated in the state of Cayman Islands, and a foreign company under the Chinese law. In analogy, Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., another representative red-chip enterprise, had not obtained and not been required to apply for approval of the Chinese competent authority before its overseas listing in 2014. A Report published by the Chinese State Administration of Foreign Exchange specifically pointed out that “domestic enterprises” were limited to legal persons registered in mainland China, which excluded Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., a Cayman Islands-based company with a Chinese background.[6]

In summary, it is fair to say that preliminary control over red-chip enterprise’s overseas listing leaves a loophole, which is partly due to China’s changing policy. That’s the reason why Didi has not been accused of violating the Chinese Securities Law but was banned for illegal accumulation of personal information, a circumvent strategy to avoid the possible information leakage brought by Didi’s public listing. Theoretically, depends on the interpretation of the aforementioned rules, the Chinese regulatory authority may have the jurisdiction to demand preliminary approval. Based on the current situation, China intends to fill the gap and is more likely to strengthen the control especially in the field concerning data security.

3. The conflict between the US’s demand for audit and China’s refusal against the US’s extraterritorial jurisdiction

Another problem is the conflict of supervision. In 2002, the US promulgated the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, under which the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (hereinafter “PCAOB”) was established to oversee the audit of public companies. Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, wherever its place of registration is, a public accounting firm preparing or issuing, or participating in the preparation or issuance of, any audit report concerning any issuer, shall register in the PCAOB and accept the periodic inspection.[7] The PCAOB is empowered to investigate, penalize and sanction the accounting firm and individual that violate the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the rules of the PCAOB, the provisions of the securities laws relating to the preparation and issuance of audit reports and the obligations and liabilities of accountants. Opposed to this provision (although not intentionally), Article 177 of the Chinese Securities Law forbids foreign securities regulatory authorities directly taking evidence in China. It further stipulates that no organization or individual may arbitrarily provide documents and materials relating to securities business activities to overseas parties without the consent of the securities regulatory authority of the State Council and the relevant State Council departments. Therefore, the conflict appears as the US requests an audit while China refused the jurisdiction of PCAOB over Chinese accountant companies.

It is suspected that despite the PCAOB’s inofficial characteristic, information (including the sensitive one) gathered by the PCAOB may be made available to government agencies, which may threaten the national security of China.[8] Consequently, China prevents the PCAOB’s inspection and some of Chinese public accounting firm’s application for registration in the PCAOB has been suspended.[9] In 2013, the PCAOB signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Chinese securities regulators that would enable the PCAOB under certain circumstances to obtain audit work papers of China-based audit firms. However, the Memorandum seems to be insufficient to satisfy the PCAOB’s requirement for supervision. The PCAOB complained that “we remain concerned about our lack of access in China and will continue to pursue available options to support the interests of investors and the public interest through the preparation of informative, accurate, and independent audit reports.”[10] After the exposure of Luckin Coffee’s accounting fraud scandal, the US promulgated the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act in 2020. This act requires certain issuers of securities to establish that they are not owned or controlled by a foreign government. Specifically, an issuer must make this certification if the PCAOB is unable to audit specified reports because the issuer has retained a foreign public accounting firm not subject to inspection by the PCAOB. If the PCAOB is unable to inspect the issuer’s public accounting firm for three consecutive years, the issuer’s securities are banned from trade on a national exchange or through other methods.

China has made “national security” its core interest and is very prudent in opening audit for foreign supervisors. From the perspective of the US, however, it is necessary to strengthen financial supervision over the public listing. As a result, Chinese enterprises have to make a choice between disappointing the PCAOB and undertaking domestic penalties. Under dual pressure of China and the US, sometimes Chinese companies involuntarily resort to delisting. This may not be a result China or the US long to see. In this situation, cooperation is a better way out.

4. Conclusion

China’s upgrading of its cybersecurity review regulation is not aimed at burning down the whole house. Overseas listing serves China’s interest by opening up channels for Chinese companies to raise funds from the international capital market, and thus contribute to the Chinese economy. The current event may be read as a sign that China is making provisions to strengthen supervision on red-chip companies’ overseas listing. It was suggested that the regulatory authority may establish a classified negative list. Enterprises concerning restricted matters must obtain the consent of the competent authority and securities regulatory authority before listing.[11] It is not bad news for foreign investors because the listed companies will undertake more stringent screening, which helps to build up an orderly securities market.

[1] http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-07/02/c_1626811521011934.htm

[2] http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-07/04/c_1627016782176163.htm; http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-07/09/c_1627415870012872.htm.

[3] http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-07/16/c_1628023601191804.htm.

[4] Notice of Cyberspace Administration of China on Seeking Public Comments on the Cybersecurity Review Measures (Draft Revision for Comment), available at: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-07/10/c_1627503724456684.htm

[5] The real seat theory is recommended by commentators, but not accepted by law. Lengjing, Going beyond audit disputes: What is the solution to the crisis of China Concept Stocks?, Strategies, Volume 1, 2021, p. 193.

[6] 2014 Cross-border capital flow monitoring report of the People’s Republic of China, available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/site1/20150216/43231424054959763.pdf

[7] Sarbanes-Oxley Act, §102(a), §104 (a) & (b).

[8] Sarbanes-Oxley Act, §105 (b)(5)(B).

[9] https://pcaobus.org/Registration/Firms/Documents/Applicants.pdf

[10] China-Related Access Challenges, available at: https://pcaobus.org/oversight/international/china-related-access-challenges.

[11] https://opinion.caixin.com/2021-07-09/101737896.html.

The Latest Development on Anti-suit Injunction Wielded by Chinese Courts to Restrain Foreign Parallel Proceedings

(This post is provided by Zeyu Huang, who is an associate attorney of Hui Zhong Law Firm based in Shenzhen. Mr. Huang obtained his LLB degree from the Remin University of China Law School. He is also a PhD candidate & LLM at the Faculty of Law in University of Macau. The author may be contacted at the e-mail address: huangzeyu@huizhonglaw.com)

When confronted with international parallel proceedings due to the existence of a competent foreign court having adjudicative jurisdiction, the seized foreign court located in common law jurisdictions seems to see it as no offence to Chinese courts by granting anti-suit injunctions to restrain Chinese proceedings. This is because the common law court believes that “An order of this kind [anti-suit injunction] is made in personam against a party subject to the court’s jurisdiction by way of requiring compliance with agreed terms. It does not purport to have direct effect on the proceedings in the PRC. This court respects such proceedings as a matter of judicial comity”. [1] However, the fact that the anti-suit injunction is not directly targeted at people’s courts in the PRC does not prevent Chinese judges from believing that it is inappropriate for foreign courts to issue an anti-suit injunction restraining Chinese proceedings. Instead, they would likely view such interim order as something that purports to indirectly deprive the party of the right of having access to Chinese court and would unavoidably impact Chinese proceedings.

The attitude of Chinese courts towards the anti-suit injunction – a fine-tuning tool to curb parallel proceedings – has changed in recent years. In fact, they have progressively become open-minded to resorting to anti-suit injunctions or other similar orders that are issued to prevent parties from continuing foreign proceedings in parallel. Following that, the real question is whether and how anti-suit injunction is compatible with Chinese law. Some argued that Article 100 of the PRC CPL provides a legal basis for granting injunctions having similar effects with anti-suit injunction at common law. [2] It provides that:

“The people’s court may upon the request of one party to issue a ruling to preserve the other party’s assets or compel the other party to perform certain act or refrain from doing certain act, in cases where the execution of the judgment would face difficulties, or the party would suffer other damages due to the acts of the other party or for other reasons. If necessary, the people’s court also could make a ruling of such preservative measures without one party’s application.” [3]

Accordingly, Chinese people’s court may make a ruling to limit one party from pursuing parallel foreign proceedings if such action may render the enforcement of Chinese judgment difficult or cause other possible damages to the other party.

In maritime disputes, Chinese maritime courts are also empowered by special legislation to issue maritime injunctions having anti-suit or anti-anti-suit effects. Article 51 of the PRC Maritime Special Procedure Law provides that the maritime court may upon the application of a maritime claimant issue a maritime injunction to compel the respondent to do or not to do certain acts in order to protect the claimant’s lawful rights and interests from being infringed. [4] The maritime injunction is not constrained by the jurisdiction agreement or arbitration agreement as agreed upon between the parties in relation to the maritime claim. [5] In order to obtain a maritime injunction, three requirements shall be satisfied – firstly, the applicant has a specific maritime claim; secondly, there is a need to rectify the respondent’s act which violates the law or breaches the contract; thirdly, a situation of emergency exists in which the damages would be caused or increased if the maritime injunction is not issued immediately. [6] Like the provision of the PRC CPL, the maritime injunction issued by the Chinese maritime court is mainly directed to mitigate the damages caused by the party’s behaviour to the other parties’ relevant rights and interests.

In Huatai P&C Insurance Corp Ltd Shenzhen Branch v Clipper Chartering SA, the Maritime Court of Wuhan City granted the maritime injunction upon the claimant’s application to oblige the respondent to immediately withdraw the anti-suit injunction granted by the High Court of the Hong Kong SAR to restrain the Mainland proceedings. [7] The Hong Kong anti-suit injunction was successfully sought by the respondent on the grounds of the existence of a valid arbitration agreement. [8] However, the respondent did not challenge the jurisdiction of the Mainland maritime court over the dispute arising from the contract of carriage of goods by sea. Therefore, the Maritime Court of Wuhan City held that the respondent had submitted to its jurisdiction. As a result, the application launched by the respondent to the High Court of the Hong Kong SAR for the anti-suit injunction to restrain the Mainland Chinese proceedings had infringed the legitimate rights and interests of the claimant. In accordance with Article 51 of the PRC Maritime Special Procedure Law, a Chinese maritime injunction was granted to order the respondent domiciled in Greece to withdraw the Hong Kong anti-suit injunction (HCCT28/2017). [9] As the maritime injunction in the Huatai Property case was a Mainland Chinese ruling issued directly against the anti-suit injunction granted by a Hong Kong court, it is fair to say that if necessary Chinese people’s court does not hesitate to issue a compulsory injunction “which orders a party not to seek injunction relief in another forum in relation to proceedings in the issuing forum”. [10] This kind of compulsory injunction is also called ‘anti-anti-suit injunction’ or ‘defensive anti-suit injunction’. [11]

When it comes to civil and commercial matters, including preserving intellectual property rights, the people’s court in Mainland China is also prepared to issue procedural orders or rulings to prevent the parties from pursuing foreign proceedings, similar to anti-suit injunctions or anti-anti-suit injunction in common law world. In Guangdong OPPO Mobile Telecommunications Corp Ltd and its Shenzhen Branch v Sharp Corporation and ScienBiziP Japan Corporation, the plaintiff OPPO made an application to the seized Chinese court for a ruling to preserve actions or inactions.[12] Before and after the application, the defendant Sharp had brought tort claims arising from SEP (standard essential patent) licensing against OPPO by commencing several parallel proceedings before German courts, a Japanese court and a Taiwanese court. [13] In the face of foreign parallel proceedings, the Intermediate People’s Court of Shenzhen City of Guangdong Province rendered a ruling to restrain the defendant Sharp from pursing any new action or applying for any judicial injunction before a Chinese final judgment was made for the patent dispute. [14] The breach of the ruling would entail a fine of RMB 1 million per day. [15] Almost 7 hours after the Chinese ‘anti-suit injunction’ was issued, a German ‘anti-anti-suit injunction’ was issued against the OPPO. [16] Then, the Shenzhen court conducted a court investigation to the Sharp’s breach of its ruling and clarified the severe legal consequences of the breach. [17] Eventually, Sharp choose to defer to the Chinese ‘anti-suit injunction’ through voluntarily and unconditionally withdrawing the anti-anti-suit injunction granted by the German court. [18] Interestingly enough, Germany, a typical civil law country, and other EU countries have also seemingly taken a U-turn by starting to issue anti-anti-suit injunctions in international litigation in response to anti-suit injunctions made by other foreign courts, especially the US court. [19]

In some other IP cases involving Chinese tech giants, Chinese courts appear to feel more and more comfortable with granting compulsory rulings having the same legal effects of anti-suit injunction and anti-anti-suit injunction. For example, in another seminal case publicized by the SPC in 2020, Huawei Technologies Corp Ltd (“Huawei”) applied to the Court for a ruling to prevent the respondent Conversant Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. (“Conversant”) from further seeking enforcement of the judgment rendered by the Dusseldorf Regional Court in Germany. [20] Before the application, a pair of parallel proceedings existed, concurrently pending before the SPC as the second-instance court and the Dusseldorf Regional Court. On the same date of application, the German regional court delivered a judgement in favour of Conversant. Within 48 hours after receiving the Huawei’s application for an anti-suit injunction, the SPC granted the injunction to prohibit Conversant from applying for enforcement of the German judgment; if Conversant failed to comply with the injunction, a fine (RMB 1 million per day) would be imposed, accumulating day by day since the date of breach. [21] Conversant applied for a reconsideration of the anti-suit injunction, and it was however rejected by the SPC eventually. [22] The SPC’s anti-suit injunction against the German regional court’s decision compelled both parties to go back to the negotiating table, and the dispute between the two parties striving for global parallel proceedings was finally resolved by reaching a settlement agreement. [23]

The SPC’s injunction in Huawei v. Conversant is commended as the very first action preservation ruling having the “anti-suit injunction” nature in the field of intellectual property rights litigation in China, which has prematurely established the Chinese approach to anti-suit injunction in judicial practice. [24] It is believed by the Court to be an effective tool to curb parallel proceedings concurrent in various jurisdictions across the globe. [25] We still wait to see Chinese court’s future approach in other civil and commercial matters to anti-suit injunction or anti-anti-suit injunction issued by itself as well as those granted by foreign courts.

———-

1. See Impala Warehousing and Logistics (Shanghai) Co Ltd v Wanxiang Resources (Singapore) Pte Ltd [2015] EWHC 811, para.144.

2. See Liang Zhao, ‘Party Autonomy in Choice of Court and Jurisdiction Over Foreign-Related Commercial and Maritime Disputes in China’ (2019) 15 Journal of Private International Law 541, at 565.

3. See Article 100, para.1 of the PRC CPL (2017).

4. See Article 51 of the PRC Special Maritime Procedure Law (1999).

5. See Article 53 of the PRC Special Maritime Procedure Law (1999).

6. See Article 56 of the PRC Special Maritime Procedure Law (1999).

7. See Huatai Property & Casualty Insurance Co Ltd Shenzhen Branch v Clipper Chartering SA (2017) E 72 Xing Bao No.3 of the Maritime Court of Wuhan City.

8. See HCCT 28/2017 of the High Court of the Hong Kong SAR.

9. See (2017) E 72 Xing Bao No.3.

10. See Andrew S. Bell, Forum Shopping and Venue in Transnational Litigation (Oxford University Press 2003), at 196.

11. See ibid.

12. See (2020) Yue 03 Min Chu No.689-1.

13. See ibid.

14. See ibid.

15. See ibid.

16. See ibid.

17. See ibid.

18. See ibid.

19. See Greta Niehaus, ‘First Anti-Anti-Suit Injunction in Germany: The Costs for International Arbitration’ Kluwer Arbitration Blog, 28 February 2021.

20. See Huawei Technologies Corp Ltd and Others v Conversant Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. (2019) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No.732, No.733, No.734-I.

21. See ibid.

22. See Conversant Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. v Huawei Technologies Corp Ltd and Others, (2019) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No.732, No.733, No.734-II.

23. See Case No.2 of the “10 Seminal Intellectual Property Right Cases before Chinese Courts”, Fa Ban [2021] No.146, the General Office of the Supreme People’s Court.

24. See ibid.

25. See ibid.

A Conflict of Laws Companion – Adrian Briggs Retires from Oxford

By Tobias Lutzi, University of Cologne

There should be few readers of this blog, and few conflict-of-laws experts in general, to whom Adrian Briggs will not be a household name. In fact, it might be impossible to find anyone working in the field who has not either read some of his academic writings (or Lord Goff’s seminal speech in The Spiliada [1986] UKHL 10, which directly credits them) or had the privilege of attending one of his classes in Oxford or one of the other places he has visited over the years.

Adrian Briggs has taught Conflict of Laws in Oxford for more than 40 years, continuing the University’s great tradition in the field that started with Albert Venn Dicey at the end of the 19th century and had been upheld by Geoffrey Cheshire, John Morris, and Francis Reynolds* among others. His writings include four editions of The Conflict of Laws (one of the most read, and most readable, textbooks in the field), six editions of Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments and his magnus opus Private International Law in English Courts, a perfect snapshot of the law as it stood in 2014, shortly before the UK decided to turn back the clock. His scholarship has been cited by courts across the world. Still, Adrian Briggs has managed to maintain a busy barrister practice in London (including well-known cases such as Case C-68/93 Fiona Shevill, Rubin v Eurofinance [2012] UKSC 46, and The Alexandros T [2013] UKSC 70) while also remaining an active member of the academic community regularly contributing not only to parliamentary committees but also, on occasion, to the academic discussion on this blog.

Adrian Briggs has taught Conflict of Laws in Oxford for more than 40 years, continuing the University’s great tradition in the field that started with Albert Venn Dicey at the end of the 19th century and had been upheld by Geoffrey Cheshire, John Morris, and Francis Reynolds* among others. His writings include four editions of The Conflict of Laws (one of the most read, and most readable, textbooks in the field), six editions of Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments and his magnus opus Private International Law in English Courts, a perfect snapshot of the law as it stood in 2014, shortly before the UK decided to turn back the clock. His scholarship has been cited by courts across the world. Still, Adrian Briggs has managed to maintain a busy barrister practice in London (including well-known cases such as Case C-68/93 Fiona Shevill, Rubin v Eurofinance [2012] UKSC 46, and The Alexandros T [2013] UKSC 70) while also remaining an active member of the academic community regularly contributing not only to parliamentary committees but also, on occasion, to the academic discussion on this blog.

To honour his impact on the field of Conflict of Laws, two of Adrian’s Oxford colleagues, Andrew Dickinson and Edwin Peel, have put together a book, aptly titled ‘A Conflict of Laws Companion’. It contains contributions from 19 scholars, including four members of the highest courts of their respective countries, virtually all of whom have been taught by (or together with) the honorand at Oxford. The book starts with a foreword by Lord Mance, followed by three short notes on Adrian Briggs as a Lecturer at Leeds University (where he only taught for about a year), as a scholar at Oxford, and as a fellow at St Edmund Hall. Afterwards, the authors of the longer academic contributions offer a number of particularly delightful ‘recollections’, describing Adrian Briggs, inter alia, as “the one time wunderkind and occasional enfant terrible of private international law” (Andrew Bell), “the perfect supervisor: unfailingly generous with his time and constructive with his criticism” (Andrew Scott), and “a tutor, colleague and friend” (Andrew Dickinson).

The academic essays that follow are conventionally organised into four categories: ‘Jurisdiction’, ‘Choice of Law’, ‘Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments’, and ‘Conflict of Laws within the Legal System’. They rise to the occasion on at least two accounts. First, they all use an aspect of Adrian Briggs’ academic oeuvre as their starting point. Second, they are of a quality and depths worthy of the honorand (possibly having profited from the prospect of needing to pass his critical eye). While they all are as insightful as inspiring, Ed Peel’s contribution on ‘How Private is Private International Law?’ can be recommended with particular enthusiasm as it picks up Adrian Briggs’ observation (made in several of his writings) that, so far as English law is concerned, “a very large amount of the law on jurisdiction, but also on choice of law, is dependent on the very private law notions of consent and obligation” and critically discusses it from the perspective of contract-law expert. Still, there is not one page of this book that does not make for a stimulating read. It is a great testament to one of the greatest minds in private international law, and a true Conflict of Laws companion to countless students, scholars, colleagues, and friends.

__

* corrected from an earlier version

News

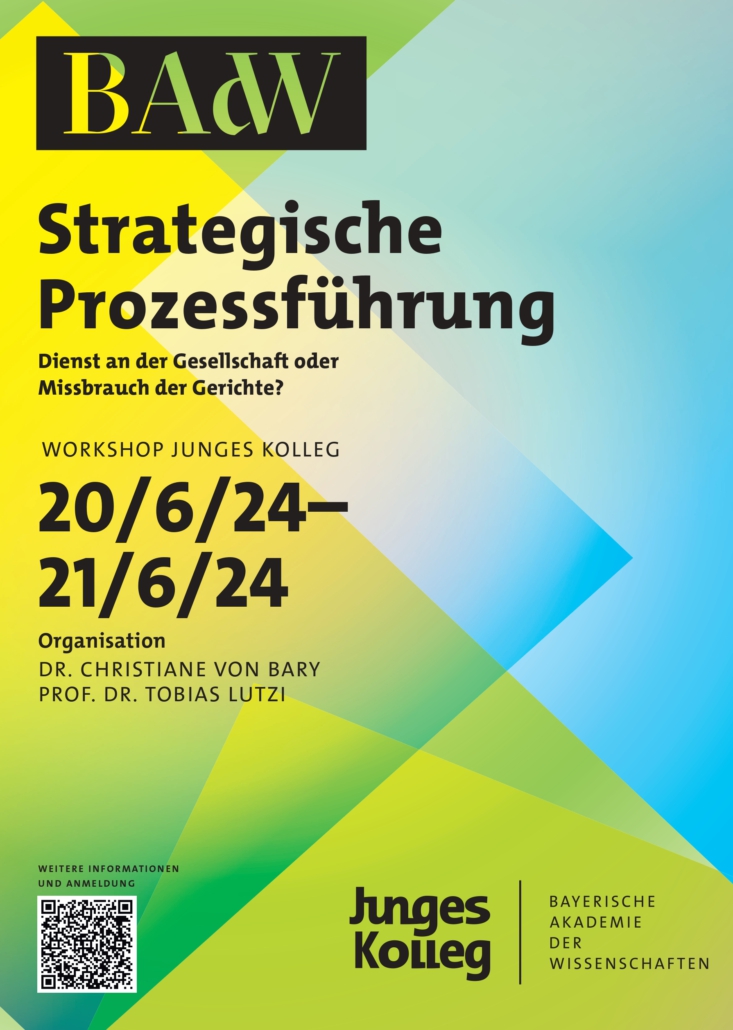

Strategic Litigation – Conference in Munich, 20/21 June 2024

On 20 and 21 June, a conference dedicated to Stratetic Litigation, organized by Christiane von Bary (LMU Munich) and Tobias Lutzi (University of Augsburg), will take place at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Munich, Germany.

The event, which will be held in German and is free of charge for all attendants, aims to tackle a variety of questions raised by a seemingly growing number of lawsuits that pursue aims beyond the dispute between the litigating parties – only some of which appear societally desireable.

The discussants, many of whom have first-hand experience, will address a number of overarching aspects such as the the role of courts in policy-making or the potential of collective-redress mechanisms and legal tech before diving more deeply into two particularly prominent examples: climate-change litigation and SLAPPs.

More information can be found on this flyer.

Please this link to register for the event.

Out now: RabelsZ 88 (2024), Issue 1

The latest issue of RabelsZ has just been released. In addition to the following articles it contains fantastic news (mentioned in an earlier post today): Starting with this issue RabelsZ will be available open access! Enjoy reading:

The latest issue of RabelsZ has just been released. In addition to the following articles it contains fantastic news (mentioned in an earlier post today): Starting with this issue RabelsZ will be available open access! Enjoy reading:

Symeon C. Symeonides, The Torts Chapter of the Third Conflicts Restatement: An Introduction, pp. 7–59, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1628/rabelsz-2024-0001 Read more

Rabels Zeitschrift Open Access

Since the beginning of this year, Rabels Zeitschrift is available in open access. For a long time, the journal has published articles in other languages than German in particular English. The new open access model should make it even more attractive for authors wishing to reach an international audience. And it enables readers from places without a subscription – not only, but also in the Global South – to have access to scholarship. What follows is a translation of the Editorial in Rabels Zeitschrift, Volume 88 (2024) / Issue 1, pp. 1-4: Open Access – was sich mit diesem Heft ändert by Holger Fleischer, Ralf Michaels, Anne Röthel, Christian Eckl, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Translation by Michael Friedman.