Views

UK Supreme Court in Okpabi v Royal Dutch Shell (2021 UKSC 3): Jurisdiction, duty of care, and the new German “Lieferkettengesetz”

by Professor Dr Eva-Maria Kieninger, Chair for German and European Private Law and Private International Law, University of Würzburg, Germany

The Supreme Court’s decision in Okpabi v Royal Dutch Shell (2021 UKSC 3) concerns the preliminary question whether English courts have jurisdiction over a joint claim brought by two Nigerian communities against Royal Dutch Shell (RSD), a UK parent company, as anchor defendant, and a Nigerian oil company (SPDC) in which RSD held 30 % of the shares. The jurisdictional decision depended (among other issues that still need to be resolved) on a question of substantive law: Was it “reasonably arguable” that RSD owed a common law duty of care to the Nigerian inhabitants whose health and property was damaged by the operations of the subsidiary in Nigeria?

In the lower instance, the Court of Appeal had not clearly differentiated between jurisdiction over the parent company and the Nigerian sub and had treated the “arguable case”-requirement as a prerequisite both for jurisdiction over the Nigerian sub (under English autonomous law) and for jurisdiction over RSD, although clearly, under Art. 4 (1) Brussels Ia Reg., there can be no such additional requirement pursuant to the CJEU’s jurisprudence in Owusu. In Vedanta, a case with large similarities to the present one, Lord Briggs, handing down the judgment for the Supreme Court, had unhesitatingly acknowledged the unlimited jurisdiction of the courts at the domicile of the defendant company under the Brussels Regulation. In Okpabi, Lord Hamblen, with whom the other Justices concurred, did not come back to this issue. However, given that from a UK point of view, the Brussels model will soon become practically obsolete (unless the UK will still be able to join the Lugano Convention), this may be a pardonable omission. It is to be expected that the English courts will return to the traditional common law restrictions on jurisdiction such as the “arguable case”-criterion and “forum non conveniens”.

Although the Supreme Court’s decision relates to jurisdiction, its importance lies in the potential consequences for a parent company’s liability on the level of substantive law: The Supreme Court affirms its previous considerations in Vedanta (2019) and rejects the majority opinion of the CoA which in 2018 still flatly ruled out the possibility of RDS owing a duty of care towards the Nigerian inhabitants. Following the appellants’ submissions, Lord Hamblen minutely sets out where the approach of the CoA deviated from Vedanta and therefore “erred in law”. The majority in the CoA started from the assumption that a duty of care can only arise where the parent company effectively “controls” the material operations of the sub, and furthermore, that the issuance of group wide policies or standards could never in itself give rise to a duty of care. These propositions have now been clearly rejected by the Supreme Court as not being a reliable limiting principle (para 145). In the present judgment, the SC affirms its view that “control” is not in itself a meaningful test, since in practice, it can take many different forms: Lord Hamblen cites with approval Lord Briggs’s statement in Vedanta, that “there is no limit to the models of management and control which may be put in place within a multinational group of companies” (para 150). He equally approves of Lord Briggs’s considerations according to which “the parent may incur the relevant responsibility to third parties if, in published materials, it holds itself out as exercising that degree of supervision and control of its subsidiaries, even if in fact it does not do so. In such circumstances its very omission may constitute the abdication of a responsibility which it has publicly undertaken” (para 148).

Whether or not the English courts will ultimately find a duty of care to have existed in either or both of the Vedanta and Okpabi sets of facts remains to be seen when the law suits have been moved to the trial of the substantive issues. Much will depend on the degree of influence that was either really exercised on the sub or publicly pretended to be exercised.

On the same day on which the SC’s judgment was given (12 February 2021), the German Federal Government publicly announced the key features of a future piece of legislation on corporate social resonsibility in supply chains (Sorgfaltspflichtengesetz) that is soon to be enacted. The government wants to pass legislation before the summer break and the general elections in September 2021, not the least because three years ago, it promised binding legislation if voluntary self-regulation according to the National Action Plan should fail. Yet, contrary to claims from civil society (see foremost the German “Initiative Lieferkettengesetz”) the government no longer plans to sanction infringements by tortious liability towards victims. Given the applicability of the law at the place where the damage occurred under Art. 4 (1) Rome II Regulation, and the fact that the UK Supreme Court in Vedanta and Okpabi held the law of Sambia and Nigeria to be identical with that of England, this could have the surprising effect that the German act, which the government proudly announced as being the strictest and most far-reaching supply chain legislation in Europe and the world (!!), would risk to fall behind the law in anglophone Africa or on the Indian sub-continent. This example demonstrates that an addition to the Rome II Regulation, as proposed by the European Parliament, which would give victims of human rights’ violations a choice between the law at the place of injury and that at the place of action, is in fact badly needed.

Webb v Webb (PC) – the role of a foreign tax debt in the allocation of matrimonial property

By Maria Hook (University of Otago, New Zealand) and Jack Wass (Stout Street Chambers, New Zealand)

When a couple divorce or separate, and the court is tasked with identifying what property is to be allocated between the parties, calculation of the net pool of assets usually takes into account certain debts. This includes matrimonial debts that that are in the sole name of one spouse, and even certain personal debts, ensuring that the debtor spouse receives credit for that liability in the division of matrimonial property. However, where a spouse owes a liability that may not, in practice, be repaid, deduction of the debt from the pool of the couple’s property may result in the other spouse receiving a lower share of the property than would be fair in the circumstances. For example, a spouse owes a debt to the Inland Revenue that is, in principle, deductible from the value of that spouse’s assets to be allocated between the parties. But the debtor spouse has no intention of repaying the debt and has rendered themselves judgment-proof. In such a case, deduction of the debt from the debtor spouse’s matrimonial property would leave the other spouse sharing the burden of a debt that will not be repaid.

This result is patently unfair, and courts have found a way to avoid it by concluding that, in order to be deductible, the debt must be one that is likely to be paid or recovered (see, eg, Livingstone v Livingstone (1980) 4 MPC 129 (NZHC)). This enquiry can give rise to conflict of laws issues: for example, there may be questions about the enforceability of a foreign judgment debt or the actionability of a foreign claim. Ultimately, the focus of the inquiry should be on the creditor’s practical chances of recovery.

In the relatively recent Cook Islands case of Webb v Webb, the Privy Council ([2020] UKPC 22) considered the relevance of a New Zealand tax debt to matrimonial property proceedings in the Cook Islands. The Board adopted a surprisingly narrow approach to this task. It concluded that the term “debts” only included debts that were enforceable against matrimonial property (which in this case was located in the Cook Islands), and that the debts in question were not so enforceable because they would be barred by the “foreign tax principle”. Lord Wilson dissented on both points.

Background

The parties – Mr and Mrs Webb – lived in the Cook Islands when they separated. Upon separation, Mr Webb returned to New Zealand. Mrs Webb commenced proceedings against Mr Webb in the Cook Islands under the Matrimonial Property Act 1976 (a New Zealand statute incorporated into Cook Islands law), claiming her share of the couple’s matrimonial property that was located in the Cook Islands.

Mr Webb, however, owed a judgment debt of NZ$ 26m to the New Zealand Inland Revenue. He argued that, under s 20(5) of the Act, this debt had to be deducted from any matrimonial property owned by him. Under s 20(5)(b), (unsecured) personal debts had to be deducted from “the value of the matrimonial property owned by” the debtor spouse to the extent that they “exceed the value of any separate property of that spouse”. Given the size of Mr Webb’s debt, the effect of s 20(5)(b) would have been to leave Mrs Webb with nothing. She argued that the debt fell outside of s 20(5)(b) because it was not enforceable in the Cook Islands and Mr Webb was unlikely to pay it voluntarily.

Whether the debt had to be enforceable against the matrimonial property in the Cook Islands

Lord Kitchin, with whom the majority agreed, concluded that s 20(5)(b) only applied to debts that were either enforceable against the matrimonial assets or likely to be paid out of those assets. Debts that were not so enforceable were not to be taken into account when dividing the matrimonial assets (unless the debtor spouse intended to pay them by using those assets in his name). A different interpretation would lead to “manifest injustice”, because if the Inland Revenue “cannot enforce its judgment against those assets, Mr Webb can keep them all for himself” (at [41]). If the Inland Revenue could not execute its judgment against the assets, and Mr Webb did not pay the debt, the reason for applying s 20(5)(b) – which was to protect a debtor spouse’s unsecured creditors – disappeared.

Lord Kitchin considered that this conclusion found support in Government of India v Taylor, where Viscount Simonds (at 508) had explained that the meaning of “liabilities” in s 302 of the Companies Act 1948 excluded obligations that were not enforceable in the English courts. The result in that case was that a foreign government could not prove in the liquidation of an English company in respect of tax owed by that company (at [42]).

In Webb, the judgment debt in question was a personal debt incurred by Mr Webb. However, Lord Kitchin seemed to suggest that the outcome would have been no different if the debt had been a debt incurred in the course of the relationship under s 20(5)(a) (at [46]). The word “debts” had the same meaning in s 20(5)(a) and (b), as referring to debts which are enforceable against the matrimonial property or which the debtor spouse intends to pay.

Lord Wilson did not agree with the Board’s interpretation. He considered that it put a gloss on the word “debts” (at [118]), and that it had “the curious and inconvenient consequence of requiring a court … to determine … whether the debt is enforceable against specified assets” (at [120]). Rather, a debt was a liability that was “likely to be satisfied by the debtor-spouse” or that was “actionable with a real prospect of recovery on the part of the creditor” (citing Fisher on Matrimonial Property (2nd ed, 1984) at para 15.6) – regardless of whether recovery would be against matrimonial or other assets (at [123]).

Applying this interpretation to the tax liability in question, Lord Wilson concluded that the liability was clearly actionable (because it had already been the subject of proceedings) and that the Inland Revenue did have a real prospect of recovery in New Zealand (at [126]-[127]). Mr Webb was living in New Zealand and was presumably generating income there, and the Commissioner had applied for the appointment of receivers of his property. This was sufficient to conclude that the debt was enforceable in New Zealand, “including on a practical level” (at [131]). The facts were different from the case of Livingstone v Livingstone (1980) 4 MPC 129, where the New Zealand Court had concluded that a Canadian tax debt could “for practical purposes” be disregarded because the debtor had already left the country at the time the demand was issued, he had no intention of returning and he had removed his assets from the jurisdiction. In such a case, if the debtor spouse were permitted to deduct the foreign tax debt without ever actually repaying it, they could take the benefit of the entire pool of matrimonial assets and thus undermine the policy and operation of the whole regime.

In our view, Lord Wilson’s interpretation is to be preferred. The relevant question should be whether the debt is one that will be practically recoverable (whether in the forum or overseas). A debt may still be practically recoverable even if it is not enforceable against the matrimonial assets and is unlikely to be paid out of those assets. It is true that, in many cases under s 25(1)(b), the chances of recovery would be slim if the matrimonial assets are out of reach and the debtor spouse has no intention of paying the debt voluntarily (which seemed to be the case for Mr Webb: at [62]). By definition, personal debts are only relevant “to the extent that they exceed the value of any separate property of that spouse”, so in practice their recoverability would depend on future or matrimonial assets. Lord Wilson’s assessment of the evidence – as allowing a finding that there was a real likelihood that Mr Webb would have to repay the debt in New Zealand – is open to question on that basis. But that doesn’t mean that the debts must be enforceable against the matrimonial assets. While this interpretation would lead to fairer outcomes under s 25(1)(b) – because it avoids the situation of the debtor spouse not having to share their matrimonial assets even though the debt is recoverable elsewhere – it could lead to strange results under s 25(1)(a), which provides for the deduction of matrimonial debts that are owed by a spouse individually. It would be unfair, under s 25(1)(a), if such debts were not deductible from the value of matrimonial property owned by the spouse by virtue of being unenforceable against that property, in circumstances where the debts are enforceable against the spouse’s personal property.

The Board’s reliance on Government of India v Taylor [1955] AC 491 (HL) in this context is unhelpful. The question before the House of Lords was whether a creditor could claim in a liquidation for a debt that would not be enforceable in the English courts (regardless of whether the debt would be enforceable over certain – or any – assets). Under the Matrimonial Property Act, on the other hand, the court is not directly engaged in satisfying the claims of creditors, so the debt need not be an obligation enforceable in the forum court. Neither need it be an obligation enforceable against matrimonial property, wherever located. It simply needs to be practically recoverable.

Whether the debt was enforceable against the matrimonial property in the Cook Islands

As we have noted, Lord Wilson argued that there was a real prospect of the debt being paid – the implication being that this was not a case about a foreign tax debt at all. Mr and Mrs Webb were New Zealanders, and Mr Webb had relocated to New Zealand before the proceedings were commenced in 2016 and had stayed there. The practical reality was that unless he found a way to meet his revenue obligations he would be bankrupted again. Lord Kitchin noted Mr Webb’s apparent determination to avoid satisfying his liabilities to the IRD. Nevertheless, there was no suggestion that Mr Webb would leave New Zealand permanently to live in the Cook Islands and there enjoy the benefits of the matrimonial property.

Nevertheless, the majority’s analytical framework required it to consider whether the tax debt was enforceable against the matrimonial property in the Cook Islands. The majority found that for the purpose of the foreign tax principle, the Cook Islands should be treated relative to New Zealand as a foreign sovereign state, despite their close historical and constitutional ties (and found that the statutory mechanism for the enforcement of judgments by lodging a memorial, cognate to the historical mechanism for the enforcement of Commonwealth judgments, did not exclude the foreign tax principle).

It was obvious that bankruptcy was a serious prospect, the IRD having appointed a receiver over Mr Webb’s assets shortly before the hearing before the Board. That begged the question whether the IRD could have recourse to the Cook Islands assets, but on this point the case proceeded in a peculiar way. The Board observed that it had been given no details of the steps that a receiver or the Official Assignee might be able to take to collect Cook Islands assets, going so far as to doubt whether the Official Assignee would even be recognized in the Cook Islands “for the Board was informed that there was no personal bankruptcy in the Cook Islands and the position of Official Assignee does not exist in that jurisdiction.” Section 655(1) of the Cook Islands Act 1915 states that “Bankruptcy in New Zealand shall have the same effect in respect to property situated in the Cook Islands as if that property was situated in New Zealand”, but the Board was not prepared to take any account of it, the provision having been introduced for the first time at the final appeal and there being some doubt about whether it was even in force.

The unfortunate consequence was that the Board gave no detailed consideration to the question of how the foreign tax principle operates in the context of cross-border insolvency, a point of considerable interest and practical significance.

The common law courts have been prepared to recognise (and in appropriate cases, defer to) foreign insolvency procedures for over 250 years, since at least the time of Solomons v Ross (1764) 1 H Bl 131, 126 ER 79 where the Court of Chancery allowed funds to be paid over to the curators of a debtor who had been adjudicated bankrupt in the Netherlands. But the relationship between this principle and the foreign tax principle has never been clear.

The UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency 1997 preserves states’ ability to exclude foreign tax claims from an insolvency proceeding. As to the common law, the New Zealand Law Commission (expressing what may be the best guide to the content of Cook Islands law) observed in 1999 that the policy justification for refusing enforcement of foreign tax judgments may not apply in the same way in the context of cross-border insolvency where the collective interests of debtors are concerned. It noted that a number of countries (including Australia, the Isle of Man and South Africa) had moved past an absolute forbidding of foreign tax claims where such claims form part of the debts of an insolvent debtor subject to an insolvency regime. It thus concluded that “foreign taxation claims may sometimes be admitted to proof in a New Zealand bankruptcy or liquidation.” While the Privy Council had a number of difficult issues to confront, it is perhaps unfortunate that they did not take the opportunity to bring clarity to this important issue.

Territorial Jurisdiction relating to Succession and Administration of Estates under Nigerian Private International Law

Issues relating to succession and administration of estate of a deceased person raise significant issues in Nigerian private international law (or conflict of laws), whether a person dies testate or intestate. In the very recent case of Sarki v Sarki & Ors,[1] the Nigerian Court of Appeal considered the issue of what court had territorial jurisdiction in a matter of succession and administration of estate of a deceased person’s property under Nigerian conflict of laws dealing with inter-state matters. While this comment agrees with the conclusion reached by the Court of Appeal, it submits that the rationale for the Court’s decision on the issue of territorial jurisdiction for succession and administration of estates under Nigerian private international law in inter-state matters is open to question.

In Sarki, the claimants/respondents were the parents of the deceased person, while the defendant/appellant was the wife of the deceased person. The defendant/appellant and her late husband were resident in Kano State till the time of his death. The deceased was intestate, childless, and left inter alia immovable properties in some States within Nigeria – Bauchi State, Gombe State, Plateau State, Kano State, Jigawa State and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The deceased’s family purported to distribute his property in accordance with Awak custom (the deceased’s personal law) with an appreciable proportion to the defendant/appellant. The defendant/appellant was apparently not pleased with the distribution and did not cooperate with the deceased’s family, who tried to gain access to the deceased’s properties. The claimants/respondents brought an action against the defendant/appellant before the Gombe State High Court. The claimants/respondents claimed inter alia that under Awak custom, which was the personal law of the deceased person, they are legitimate heirs of his property, who died childless and intestate; a declaration that the distribution made on 22 August 2015 by the deceased’s family in accordance with Awak custom, giving an appreciable sum of the property to the defendant/appellant is fair and just; an order compelling the defendant/appellant to produce and hand over all the original title documents of the landed properties and boxer bus distributed by the deceased family on 22 August 2015; and cost of the action. In response, the defendant/appellant made a statement of defense and counter-claim to the effect that she and the deceased are joint owners of all assets and properties acquired during their marriage; a declaration that the estate of the deceased is subject to rules of inheritance as envisaged by marriage under the Marriage Act[2] and not native law and custom; a declaration that as court appointed Administratrix, she is entitled to administer the estate of the deceased person; an order of injunction restraining the claimants/respondents to any or all of the assets forming part of the estate of the deceased person based on custom and tradition; and costs of the action.

The Gombe State High Court held that the Marriage Act was applicable in distributing the estate of the deceased person and not native law and custom. However, the Court distributed the property evenly between the claimants/respondents and defendant/appellants on the basis that it will be unfair for the claimants/respondents as parents of the deceased not to have access to the deceased’s property. The defendant/appellant successfully appealed this ruling and won on the substantive aspect of the case. The private international law issue was whether the Gombe State High Court had territorial jurisdiction in this case, rather than the Kano State High Court where the defendant/appellant alleged the cause of action arose? The defendant/appellant argued that the cause of action arose exclusively in Kano State because that is where the deceased lived and died, and the defendant/appellant had obtained letters of administration issued by the Kano State High Court. The defendant/appellant lost on this private international law issue.

The Court of Appeal began on the premise that the issue of whether Gombe State or Kano State had jurisdiction was a matter of private international law, and not an issue of that was governed by a States’ civil procedures rules that governs dispute within a judicial division.[3] It also held that it is the plaintiff’s statement of claim that determines jurisdiction.[4] The Court of Appeal then approved its previous decisions that in inter-state matters of a private international law matter, a State High Court is confined to the location of the cause of action.[5] In this connection, the Court of Appeal rejected the argument of counsel for the defendant/appellant and held that the cause of action arose both in Kano and Gombe State – the latter State being the place where the dispute arose with the deceased’s family on the distribution of the deceased’s estate. Thus, both the Kano State High Court and Gombe State High Court could assume jurisdiction over the matter.[6] The Court of Appeal further held that other States such as Kano, Bauchi and Plateau could also assume jurisdiction because letters of administration were granted by the State High Courts of these jurisdictions.[7] In the final analysis, the Court of Appeal held that the claimants/respondents could either institute its action in either Gombe, Kano, Bauchi and Plateau – being the place where the cause of action arose, but procedural economy (which leads to convenience, saving time, saving costs, and obviates the risk of conflicting orders) encouraged the claimants/respondents to concentrate its proceedings in one of these courts – Gombe State High Court in this case.[8] Accordingly, this private international law issue was resolved in favour of the claimants/respondents.

There are three comments that could be made about the Court of Appeal’s judgments. First, it appears the issue of territorial jurisdiction was raised for the first time on appeal. It does not appear that this issue was raised at the lower court. If this is the case, it is submitted that the defendant/appellant should have been deemed to have waived its procedural right on jurisdiction on the basis that it submitted to the jurisdiction of the Gombe State High Court. Matters of procedural jurisdiction can be waived by the parties but not substantive jurisdiction such as jurisdiction mandatorily prescribed by the constitution or enabling statutes in Nigeria.[9] The issue of territorial jurisdiction among various State High Courts was a procedural matter and should have been raised promptly by the defendant/appellant or it would be deemed to have waived its right to do so by submitting to the jurisdiction of the Gombe State High Court.

Second, the Court of Appeal appeared to miss the point that there are Nigerian Supreme Court authorities that addressed the issue before it. According to the Supreme Court of Nigeria, in matters of succession and administration of states, the lex situs is given a predominant role for matters of jurisdiction purposes so that a Nigerian court would ordinarily not assume jurisdiction over foreign property, whether in an international or inter-state matter. Nigerian courts, as an exception, apply the rule to the effect that, where the Court has jurisdiction to administer an estate or trust, and the property includes movables or immovables situated in Nigeria and immovables situated abroad, the court has jurisdiction to determine questions of title to the foreign immovables for the purpose of administration. Again Nigerian courts apply this rule both in inter-State and international matters.[10] This rule established by the Nigerian Supreme Court in accordance with the English common law doctrine should have guided the Court of Appeal to hold that since it had jurisdiction over the deceased immovable properties in Gombe State, it also had jurisdiction over other immovable properties constituting the deceased’s estate in other States in Nigeria. The issue of where the cause of action arose was clearly irrelevant.

This brings me to the third and final comment – where the cause of action arose – the issue of territorial jurisdiction. The Nigerian Supreme Court has held in some decided cases that in inter-state matters, a State High Court cannot assume jurisdiction over a matter where the cause of action is exclusively located in another State, irrespective of whether the defendant is resident and willing to submit to the court’s jurisdiction.[11] This current approach by the Supreme Court may have influenced the Court of Appeal to be fixated on the issue of territorial jurisdiction and confining itself to where the cause of action arose. Looking at the bigger picture, the current approach of the Nigerian Supreme Court in relation to matters of action in personam demonstrates a clear misunderstanding of applying common law private international law matters of jurisdiction in inter-state matters.[12] If a defendant is resident in a State and/or willing to submit, it shouldn’t matter where the cause of action arose in inter-state and international matters. Indeed, there is no provision of the Nigerian 1999 Constitution or enabling statute that prohibits a State High Court from establishing extra-territorial jurisdiction in inter-state or international matters, provided the defendant is resident and/or wiling to submit to the Court’s jurisdiction. The current approach of the Nigerian Supreme Court unduly circumscribes the jurisdiction of the State High Courts in inter-state matters, and also risks making Nigerian courts inaccessible in matters of international commercial litigation in matters that occur exclusively outside Nigeria, thereby making the Nigerian court commercially unattractive for litigation, and resulting in injustice.[13] Therefore it is time for the Supreme Court to overrule itself and revert to its earlier approach that held that in inter-state or international matters a Nigerian court can establish jurisdiction, irrespective of where the cause of action arose, provided the defendant is resident and/or submits to the jurisdiction of the Nigerian court.[14]

In my final analysis, I would state that the Court of Appeal in Sarki reached the right conclusion on the issue of private international law, but the rationale for its decision is open to question. Moreover, though this private international law issue was resolved against the defendant/appellant, it substantially won on the substantive issues in the case. If this case goes on appeal to the Supreme Court, it should be an opportunity for the Supreme Court to set the law right again on the concept of jurisdiction in matters of succession and administration and estates, and overrule itself where it held that in inter-state matters, a State High Court is restricted to the place where the cause of action arose, irrespective of whether the defendant is resident and/or willing to submit to its jurisdiction.

[1] (2021) LPELR – 52659 (CA).

[2] Cap 218 LFN 1990.

[3]Sarki (n 1) 13-14.

[4] Ibid 14.

[5] Ibid 14-18, approving Lemit Engineering Ltd v RCC Ltd (2007) LPELR-42550 (CA).

[6] Sarki (n 1) 21.

[7]Ibid 21-3.

[8] Ibid 23-5, approving Onyiaorah v Onyiaorah (2019) LPELR-47092 (CA).

[9] See generally Odua Investment Co Ltd v Talabi ( 1997 ) 10 NWLR (Pt. 523) 1 ; Jikantoro v Alhaji Dantoro ( 2004 ) 5 SC (Pt. II) 1, 21 . This is a point that has been stressed by Abiru JCA in recent cases such as Khalid v Ismail ( 2013 ) LPELR-22325 (CA ); Alhaji Hassan Khalid v Al-Nasim Travels & Tours Ltd ( 2014 ) LPELR-22331 (CA) 23 – 25 ; Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation v Zaria ( 2014 ) LPELR-22362 (CA) 58 – 60; Obasanjo Farms (Nig) Ltd v Muhammad ( 2016 ) LPELR-40199 (CA). See also The Vessel MT. Sea Tiger & Anor v Accord Ship Management (HK) Ltd (2020) 14 NWLR (Pt. 1745) 418.

[10] Ogunro v Ogedengbe (1960) 5 SC 137; Salubi v Nwariaku (2003) 7 NWLR 426.

[11] Capital Bancorp Ltd v Shelter Savings and Loans Ltd (2007) 3 NWLR 148; Dairo v Union Bank of Nigeria Plc (2007) 16 NWLR (Pt 1059) 99; Mailantarki v Tongo & Ors (2017) LPELR-42467; Audu v. APC & Ors (2019) LPELR – 48134.

[12]See generally Abiru JCA in Muhammed v Ajingi (2013) LPELR-20372 (CA) 23 – 25, 25 – 26; CSA Okoli and RF Oppong, Private International Law in Nigeria (1st edition, Hart, Oxford, 2020) 95-103; AO Yekini, “Comparative Choice of Jurisdiction Rules in Cases having a Foreign Element: are there any Lessons for Nigerian Courts?” (2013) 39 Commonwealth Law Bulletin 333; Bamodu O., “In Personam Jurisdiction: An Overlooked Concept in Recent Nigerian Jurisprudence” (2011) 7 Journal of Private International Law 273.

[13] See for example First Bank of Nigeria Plc v Kayode Abraham (2003) 2 NWLR 31 where the Court of Appeal held the lower court did not have jurisdiction because the cause of action arose exclusively outside Nigeria. This decision was however overturned by the Supreme Court in First Bank of Nigeria Plc v Kayode Abraham (2008) 18 NWLR (Pt 1118) 172 on other dubious grounds. For a critique, see CSA Okoli and RF Oppong, Private International Law in Nigeria (1st edition, Hart, Oxford, 2020) 90.

[14] See generally Nigerian Ports Authority v Panalpina World Transport (Nig) Ltd (1973) 1 ALR Comm 146, 172; British Bata Shoe Co v Melikan (1956) SCNLR 321. See also Barzasi v Visinoni (1973) NCLR 373., 381-2.

News

University of Geneva: Executive Training on Civil Aspects of International Child Protection (ICPT) – 2024-2025

The University of Geneva is organising the second edition of the Executive Training on Civil Aspects of International Child Protection (ICPT).

The University of Geneva’s ICPT, offered by the Children’s Rights Academy, is designed to:

- Explore innovative approaches to uphold the fundamental rights of children in transnational situations

- Learn best practices for supporting unaccompanied minors and displaced children seeking asylum

- Collaborate with experts from various fields to create holistic and effective child protection strategies

- Understand the dynamics of how different organisations and stakeholders can work together to protect children

Programme of the 2nd Round 2024 – 2025:

Module 1: Children’s Individual Rights in Transnational Parental Relationships

28 November 2024, 14:15 – 18:15

Module 2: International and Comparative Family Law

19 December 2024, 14:15 – 18:15

Module 3: Vulnerable Migration

27 February 2025, 14:15 – 18:15

Module 4: Practice of Child Protection Stakeholders: Inter-agency Co-operation in Context

10 April 2025, 14:15 – 18:15

This training programme is designed for a diverse audience, including child protection professionals, legislators and lawyers, researchers, students, international organisation staff members, and governmental authorities, among others.

For queries related to the content of the programme, please contact vito.bumbaca@unige.ch.

For more information, please visit the website. To register click here.

The e-mail address is cra-secretariat@unige.ch.

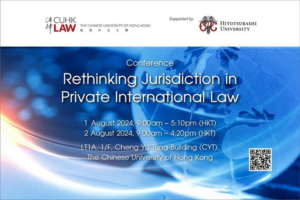

Conference on Rethinking Jurisdiction in Private International Law (1 & 2 August 2024 @ CUHK)

This information is kindly provided by Dr. King Fung (Dicky) Tsang, Associate Professor, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

CUHK LAW will host an international conference on private international law from August 1, 2024, to August 2, 2024.

Theme

The theme of the conference is “Rethinking Jurisdiction in Private International Law.” Jurisdiction is a broad concept in private international law that includes legislative, judicial, and enforcement aspects. Over the past few years, there have been significant developments in the area of jurisdiction across various countries. These developments, while rooted in national law, have extensive cross-border impacts. Additionally, the HCCH Jurisdiction Project has engaged many countries in focusing on jurisdictional issues and seeking to harmonize jurisdictional conflicts. This conference offers a forum for academics and practitioners to rethink and exchange ideas on the evolving new features of “jurisdiction” in the context of private international law.

This conference is supported by Hitotsubashi University.

Speakers, Abstracts and Programme:

The lists of the speakers, abstracts and the programme can be found respectively here, here and here

Venue:

The Conference will be held at the Cheng Yu Tung Building (CYT) which is located in Sha Tin, Hong Kong.

Address:

LT1A, 1/F, Cheng Yu Tung Building (CYT), The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Map)

Transportation:

MTR: Get off at the University Station. CYT Building is just 1-minute walk away from Exit B.

Languages:

The first day will be conducted in English, while the second day will mainly be in Mandarin Chinese. Attendees are welcome to participate in sessions on both days.

Details and registration

Please visit the conference website for more details. If you would like to attend, kindly register here by 31 July 2024, 3:00 pm.

For enquiries, please contact CUHK LAW at law@cuhk.edu.hk.

FACULTY OF LAW

The Chinese University of Hong Kong | Shatin, NT, Hong Kong SAR, China

T: +852 3943 4399 | E: law@cuhk.edu.hk | W: https://www.law.cuhk.edu.hk

Revue Critique de droit international privé – issue 2024/1

Written by Hadrien Pauchard (assistant researcher at Sciences Po Law School)

The first issue of the Revue Critique de droit international privé of 2024 was released a few months ago. It contains 2 articles and several case notes. Once again, the doctrinal part has been made available in English on the editor’s website (for registered users and institutions).

The opening article is authored by Dr. Nicolas Nord (Université de Strasbourg) and tackles the crucial yet often overlooked issue of L’officier d’état civil et le droit étranger. Analyse critique et prospective d’une défaillance française (Civil registrars and foreign law. A critical and prospective analysis of a French failure). Its abstract reads as follows:

In international situations, French civil registrars may frequently be confronted with the application of foreign law. However, by virtue of the General Instruction on Civil Status and other administrative texts, they are under no obligation to establish the content of foreign law and can be satisfied with the sole elements reported by requesting private individuals. This solution certainly has the advantage of simplifying the task of civil registrars, who are not legal professionals. However, it leads to inconsistencies within the French legal system. The article therefore recommends reversing the principle and creating a duty for the French authority in this area. However, the burden should be lightened by facilitating access to the content of foreign law. Concrete proposals are put forward to this end, both internally and through international cooperation.

In the second article, Prof. David Sindres (Université d’Angers) addresses the complex question of the scope of jurisdiction clauses, through the critical discussion of recent case law on whether Le « destinataire réel » des marchandises peut-il se voir opposer la clause attributive de compétence convenue entre le chargeur et le transporteur maritime ? (Can the “actual addressee” of the goods be submitted to the jurisdiction clause agreed between the shipper and the maritime carrier?). The abstract reads as follows:

In two notable decisions, the French Cour de cassation has ruled that the case law of the Court of Justice Tilly Russ/Coreck Maritime is strictly confined to the third-party bearer of a bill of lading or sea waybill, and cannot be applied to the “actual addressee” of the goods. Thus, unlike the third party bearer, the “actual addressee” cannot be submitted to the clause agreed between the shipper and the maritime carrier and inserted in a bill of lading or a sea waybill, even if he has succeeded to the rights and obligations of the shipper under the applicable national law, or has given his consent to the clause under the conditions laid down in article 25 of the Brussels I bis regulation. The distinction thus made by the Cour de cassation with regard to the enforceability against third parties of jurisdiction clauses agreed between shippers and carriers cannot be easily justified. Indeed, it is in no way required by the Tilly Russ and Coreck Maritime rulings and is even difficult to reconcile with them. Furthermore, insofar as it may lead to the non-application of a jurisdiction clause to an actual addressee who has nevertheless consented to it under the conditions of article 25 of the Brussels I bis regulation, it fails to meet the requirements of this text.

The full table of contents is available here.

The second issue of 2024 has been released and will be presented shortly on this blog.

Previous issues of the Revue Critique (from 2010 to 2022) are available on Cairn.