The Data Protection Conflict: The EU General Data Protection Regulation 2016 and India’s Personal Data Protection Bill 2019

By Anubhav Das (National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi) and Aditi Jaiswal (Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow)

The internet brought significant changes in society, leading to a massive collection of data which necessitated legislation to regulate such data collection. The European Union enacted the General Data Protection Regulation, 2016(Hereafter GDPR), replacing the Data Protection Directive, 1995. Meanwhile, India, which currently lacks a separate data protection legislation, is in the process of enacting the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (Hereafter PDP). The PDP has been introduced in the Indian parliament and is currently under the scrutiny of a parliamentary committee. The primary purpose of these legislations is the protection of informational privacy.

Even though GDPR and PDP follow the same set of data protection principles, but, there exists an inevitable conflict between the two. This conflict determines the applicability of the legislation on the data subject. The territorial scope of GDPR and the PDP makes it clear that both overlap each other and this overlap can be used by companies involved in data processing or collection, to circumvent the civil liability arising under the laws. This post analyses the conflict between both the laws and in conclusion, it will suggest a way to overcome such an issue.

Territorial Scope: GDPR and PDP

Article 3 of the GDPR provides for the territorial applicability of the law. The Regulation applies to the processing of personal data by a controller or a processer. According to Article 3(1), any controller or processer that is established in the member state (European Union) shall fall under the scope of the GDPR. In other words, any company which has an office in the European Union shall come within the purview of the GDPR. Article 3(2) states that even if any processer or controller is not established in the European Union, but if they are offering goods or services irrespective of payment or monitoring behaviour in the European Union, then they will also fall under the scope of GDPR.

On the other hand, the PDP provides for the territorial applicability under Section 2. It applies to the processing of personal data by data fiduciary (similar to the controller under GDPR) and data processer (similar to processer under GDPR). Section 2(A) (a) states that if personal data is collected, disclosed, shared or otherwise processed within the territory of India, then it shall fall under the PDP. Section 2(A) (b), makes it applicable to the State, any Indian company, any citizen of India or any person or body of persons incorporated or created under Indian law. Section 2 (A) (c) makes it applicable to data fiduciary or data processor which are not in India but are processing in connection with any business carried on in India, or any systematic activity of offering goods or services to data principals within the territory of India or any activity concerning the profiling of data principle.

The Overlap of Jurisdiction

The internet has provided a way for companies to operate anywhere without the existence of an entity in a particular country. This also includes those companies which deal with data. In the context of Europe and India, a company doesn’t need to have an entity in Europe or India to operate and do business. Thus, an Indian company can easily do business related to data in Europe without any real existence in Europe and vice versa. Consequently, the problem that arises concerning data protection laws is complicated. An Indian company will fall under the purview of the PDP as per Section 2(A) (b) but at the same time if this Indian company also deals with ‘personal data for offering goods or services’ in the European Union, then it will also be regulated by the provisions of the GDPR.

Similarly, a European company ‘collecting data in India’ will fall under the scope of both PDP and GDPR. It is a matter of fact that judicial courts do not have jurisdiction over foreign land. Hence, no monetary damages can be imposed on companies which operate from Europe by using PDP or companies operating from India by using GDPR.

A European company or an Indian company can also claim that there is proper compliance with GDPR or PDP, respectively. In the context of Europe and India, a company only needs to follow the data protection law of the land from where it operates even though such an act violates data protection law of the other jurisdiction. This is possible as GDPR and PDP differ from each other on every key and essential aspect such as the very meaning of personal data.

The Difference and its Implications

The primary purpose of GDPR and PDP is the protection of personal data. But, the definition of personal data differs when GDPR is compared with PDP. The reason why such a description is essential is that a substantial part of both laws is based on the processing of personal data. This includes fair consent, purpose limitation, storage limitation, rights of data principle etc. Such aspects, when read with the territorial scope of both the laws, outlines the applicability of its provisions. The table below shows the difference in the definition of personal data.

| GDPR | PDP | |

|

Personal data is data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable, having regard to any characteristic, trait, attribute or any other feature of the identity of such natural person, whether online or offline, or any combination of such features with any additional information, and shall include any inference drawn from such data for profiling.

|

Note – Underlined are the parts which show that it is not present in the other law.

Both GDPR and PDP refer to personal data as information/data relating to identified/identifiable natural person. At the same time, the nuances of what constitutes an identifiable natural person differ significantly as both use different terminology which creates a diversion in the meaning of the personal data.

Deviation 1 – PDP provides for words such as ‘any other feature of identity, a combination of such feature with other information, any inference drawn for profiling’, in the meaning of an identifiable natural person. These terms can be interpreted more liberally and will probably be explained by courts in India and shall have an evolving meaning. GDPR, on the other hand, provides for specific terms like ‘physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, social identity’. Hence, European Courts will have to interpret personal data by mandatorily considering such terms, making it’s scope narrower when compared to PDP in this context.

Deviation 2 – Terms such as ‘identification number’ and ‘location data’ is mentioned explicitly in GDPR and not in PDP, making PDP narrower in scope here.

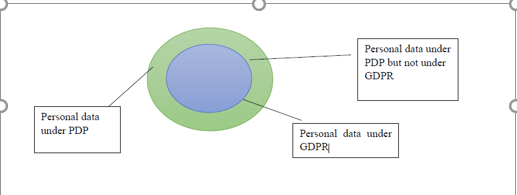

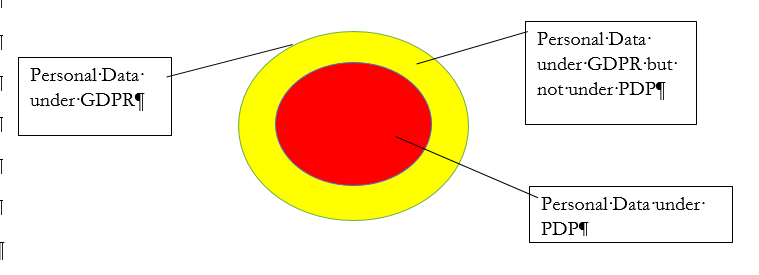

This above discussion can be easily understood with the help of the following figure –

Deviation 1 – The green circle represents inference in PDP. The blue circle represents inference in GDPR. The green stripe represents personal data which is covered in PDP and not covered in GDPR.

Deviation 2 – The yellow circle represents personal data in GDPR. The red circle represents personal data in PDP. The yellow stripe represents personal data which is covered in GDPR and not covered in PDP.

In the figure above, in Deviation 1, the green strip represents that personal data, which when processed by a company shall not fall under the scope of GDPR even though it shall be under the scope of the PDP. Such a difference implies that companies falling under the territorial ambit of both the laws, can follow one and circumvent the other.

A European company can process personal data represented in the green strip from India, and for that, it doesn’t need to comply with GDPR as that data is not personal data under GDPR. Now even though, there is a violation of the provisions under PDP the company can escape liability as Indian courts do not have jurisdiction in Europe, and European Courts cannot adjudge the matter as it falls outside the material scope of GDPR. The vice versa will happen if the case of deviation two is considered.

The consequence of such inconsistencies will be faced by data subjects who won’t be able to claim damages provided under their respective data protection law. One of the ways to ensure that damages can be claimed is by harmonising the data protection laws which can only be done by international cooperation.

The Need For International Cooperation in Data Protection

The existence of such issues in the framework of GDPR and PDP is not because of the extraterritorial application. Advocating against the extraterritorial application to resolve the problem of overlap in the jurisdiction of data protection laws would only give rise to more infringement of informational privacy of data subjects by foreign companies. This, in turn, will be detrimental for the very purpose for which data protection legislation is enacted.

The requirement at present is to harmonise the key definitions such as personal data in the data protection legislation. This will ensure that a right of action lies in both GDPR and PDP. Even if a foreign company cannot be dragged to the national court, harmonisation will at least ensure that a data subject has a right to seek damages in the international court.

The aspect discussed in this article is regarding two jurisdictions. However, consider, for instance, the complications that could arise when more than two jurisdictions are involved. To illustrate, an Indian Company having an office in Canada and that office is doing business in data from the European Union. In such cases, the best way to ensure data protection rights is by harmonisation, and this can only be achieved with the help of international cooperation. Thus, data protection in the age of internet needs multilateral international agreements.

Conclusion

The international regime of data protection is complicated in today’s world. There is no proper international agreement which governs the data protection legislation across the globe, which resulted in a difference in the critical terms of data protection when GDPR and PDP are compared. This, in – turn can be used by corporates to get away with liability. So, the aim must be not to let anyone violate the data protection principles by using this inconsistency and get away with it. To deal with this and safeguard the privacy of data subject, international cooperation in data protection is essential.