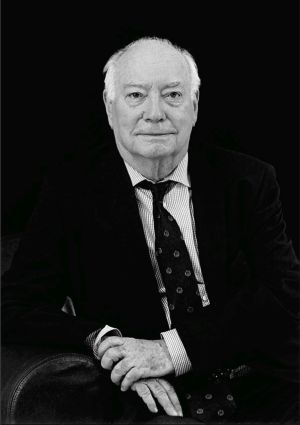

In Memoriam Erik Jayme (1934-2024)

With great sadness did we receive notice that Erik Jayme passed away on 1 May 2024, shortly before his 90th birthday on 8 June. Everyone in the CoL and PIL world is familiar with and is probably admiring his outstanding and often path-breaking work as a global scholar. Those who met him in person were certainly overwhelmed by his humour and humanity, by his talent to approach people and engage them into conversations about the law, art and culture. Anyone who had the privilege of attending lectures of his will remember his profound and often surprising and unconventional views, paths and turns through the subject matter, often combined with a subtle and entertaining irony.

Erik Jayme was born in Montréal, as the son of a German Huguenot of French origin and a Norwegian. The parents had married in Detroit before a protestant priest. What else if not a profound interest in cross-border relations, different cultures and languages as well as bridging cultural differences and, ultimately, Private International Law could have been the result? “There was no other way“, as he put it once. His father, Georg, born on 10 April 1899 in Ober-Modau in South Hesse of Germany, passed away on 1 January 1979 in Darmstadt, later became a professor of what today would probably be called chemical engineering, with great success, on cellulose production technologies at the University of Darmstadt. His passion for collecting Expressionist and 19th century art undoubtedly served as an inspiration for Erik to later devote himself to art, art history and finally art law. During his youth, as Erik mentioned once, he would use his (exceptionally broad) knowledge on art and any aspect of culture that crossed his mind to draw his tennis partners into sophisticated and demanding conversations on the court. Perhaps not least with a view to his father’s expectations, Erik decided to study law at the University of Munich, but added courses in art history to his curriculum. He liked to recall, how he approached the world-famous art historian, Hans Sedlmayr, to ask him whether he might allow him to attend his seminars, despite being (“unfortunately“) a law student. Sedlmayr replied that Spinoza had been wise to be grinding optical lenses to earn a living, and in light of a similar wisdom that the applicant showed, he was accepted.

In 1961, at the age of 27, Erik Jayme delivered his doctoral thesis on „Spannungen bei der Anwendung italienischen Familienrechts durch deutsche Gerichte“ (“Tension in the application of Italian family law by German courts“).[1] While clerking at the court of Darmstadt, Erik Jayme published his first article in this field, inspired by a case in which he was involved. International family and succession law as well as questions of citizenship became a focus of his academic research and publications for decades, including his Habilitation in 1971 on „Die Familie im Recht der unerlaubten Handlungen” (“The Family in Tort Law“),[2] in particular with a view to relations connected with Italy. This may show early traces of what became more apparent later: More than others, Erik Jayme took the liberty to make use of law, legal research and academia to build his own way of life (that should definitely include Italy), inspired by seemingly singularities in a concrete case that would be seen as a sign for something greater and thus transformed into theories and concepts, enriched by a dialogue with concepts from other fields such as art history. Is this way of producing creativity also the source of what later rocked the private international law of South America: the « diálogo das fontes como método »?[3] His research on Pasquale Stanislao Mancini,[4] later combined with studies on Anton Mittermaier,[5] Giuseppe Pisanelli [6] and Emerico Amari [7] as well as on Antonio Canova [8] were received as leading works on conceptual developments in the fields of choice of law, international civil procedural law, comparative law as well as international art and cultural property law, and over time, Erik Jayme became one of the world leading and most influential scholars in the field. The substantial contribution Erik Jayme provided to the work of The Hague Academy of International law, was perfectly summarized in Teun Struycken’s « Hommage à Erik Jayme » delivered in 2016 on behalf of the Academy’s Curatorium:[9]

« Vous n’avez cessé de souligner que les systèmes de droit ne s’isolent pas de la société humaine, mais s‘y imbriquent. Ils sont même des expressions de la culture des sociétés. La culture s’exprime aussi et surtout dans les beaux arts. »

Speaking of art and cultural property law: It seems to be the year of 1990 when Erik Jayme published for the first time a piece in this field, namely a short conference report on what has now become an eternal question: „Internationaler Kulturgüterschutz: lex originis oder lex rei sitae“ (“Protection of international cultural property: lex originis or lex rei sitae“).[10] In 1991, his seminal work on „Kunstwerk und Nation: Zuordnungsprobleme im internationalen Kulturgüterschutz“ (“Artwork and nation: Problems of attribution in the international protection of cultural property“)[11] appeared as a report for the historical-philosophical branch of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences where he traced back the notion of a “home“ (« une patrie » ) of an artwork to Antonio Canova‘s activities as the Vatican’s diplomate at the Congress of Vienna where Canova, a sculptural artist by the way, succeeded in bringing home the cultural treasures taken by Napoléon Bonaparte from Rome to Paris (into the newly built Louvre) back to Rome (into the newly built Museo Chiaramonti), despite the formal legalisation of this taking in the Treaty of Tolentino of 1797. “This is where the notion of a lex originis was born”. Still in 1991, the Institut de Droit International concluded under the leadership of Erik Jayme, in its Resolution of Basel « La vente internationale d’objets d’arts sous l’angle de la protection du patrimoine culturel » in its Art. 2: « Le transfert de la propriété des objets d’art – appartenant au patrimoine culturel du pays d’origine du bien – est soumis à la loi de ce pays » . Much later, in 2005, when I had the privilege of travelling with him to the Vanderbilt Law School and the Harvard Law School for presentations of ours on „Global claims for art“, he further developed his vision of a work of art as quasi-persons who should be conceived as having their own cultural identity,[12] to be located at the place where the artwork is most intensely inspiring the public and thus is “living“. From there it was only a small step to calling for a guardian ad litem for an artwork, just as for a child, in legal proceedings. When Erik Jayme was introduced to the audiences in Vanderbilt and Harvard, the academic hosts would usually present him, in all their admiration, as “a true Renaissance man“. I would believe that he felt more affiliated to the 19th century, but this might not necessarily exclude the perception of him as a “Renaissance man“ from a transatlantic perspective, all the more as there seems to be no suitable term in English for the German „Universalgelehrter“ (literally: “universal scholar”).

This is just a very small fraction of Erik Jayme’s amazingly wide-ranging, rich and influential scholarly life and of his extraordinarily inspiring personality. Many others may and should add their own perspectives, perhaps even on this blog. We will all miss him, but he will live on in our memories!

[1] Jayme, Spannungen bei der Anwendung italienischen Familienrechts durch deutsche Gerichte, Gieseking 1961 (LCCN 65048319).

[2] Jayme, Die Familie im Recht der unerlaubten Handlungen, Metzner 1971 (LCCN 72599373).

[3] Jayme, « Identité culturelle et intégration: le droit international privé postmoderne », Recueil des Cours 251 (1995), 259 (Recueil des cours en ligne).

[4] See e.g. Jayme, Pasquale Stanislao Mancini : internationales Privatrecht zwischen Risorgimento und praktischer Jurisprudenz, Gremer 1990 (LCCN 81116205).

[5] Jayme, „Italienische Zustände“, in: Moritz/Schroeder (eds.), Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier (1787-1867) – Ein Heidelberger Professor zwischen nationaler Politik und globalem Rechtsdenken“, Regionalkultur 2009, pp. 29 et seq.

[6] See e.g. Jayme, « Giuseppe Pisanelli fondatore della scienza del diritto processuale civile internazionale », in: Cristina Vano (eds.), Giuseppe Pisanelli – Scienza del processo – cultura delle leggi e avvocatura tra periferiae nazione, Neapel 2005, pp. 111 e seguenti (LCCN 2006369541).

[7] See e.g. Jayme, « Emerico Amari: L’attualità del suo pensiero nel diritto comparato con particolare riguardo alla teoria del progresso », in: Fabrizio Simon (ed.), L’Identità culturale della Sicilia risorgimentale, Atti del convegno per il bicentenario della nascita di Emerico Amari e di Francesco Ferrara, in Storia e Politica – Rivista quadrimestrale III, N.°2/2011, pp. 60 e seguenti.

[8] See e.g. Jayme, Antonio Canova (1757-1822) als Künstler und Diplomat: Zur Rückkehr von Teilen der Bibliotheca Palantina nach Heidelberg in den Jahren 1815 und 1816, Heidelberg 1994 (LCCN 95207445).

[9] V.M. Struycken, « Hommage à Erik Jayme », Session du Curatorium du 15 janvier 2016 à Paris (disponible ici: https://www.hagueacademy.nl/2016/02/hommage-a-dr-erik-jayme/?lang=fr).

[10] Jayme, „Internationaler Kulturgüterschutz: lex originis oder lex rei sitae“, IPRax 1990, 347.

[11] Jayme, Kunstwerk und Nation: Zuordnungsprobleme im internationalen Kulturgüterschutz, C. Winter 1991.

[12] See e.g. Jayme, “Gobalization in Art Law: Clash of Interests and International Tendencies”, Vand. J. Int. L. 38 (2005), 927, 938 et seq.

Thank you, Matthias, for a wonderful glimpse into all that Erik Jayme meant to so many of us. He will be missed by those who were privileged to know him personally.

As a Portuguese, I was overwhelmed by his knowledge of our law and its historical development. It suffices to say that he, not a Portuguese, or a Brazilian, for example, is credited as the proponent of a «Lusophone legal family» as a category in comparative law. But even more striking was the way he grasped cultural particularities of different nations united (or separated) by the same language, allowing him to be the pivot of so many bonds between Portuguese-speaking scholars, especially from Brazil and Portugal, namely through the German-Lusophone Lawyers Association he has founded and directed for many years, and of which he was to his last day an honorary President.

For all those who deal with conflict of laws, Erik Jayme’s life and work are a lesson of profound humanity, openness, empathy with others, and creativity.