Traveling Judges and International Commercial Courts

Written by Alyssa S. King and Pamela K. Bookman

International commercial courts—domestic courts, chambers, and divisions dedicated to commercial or international commercial disputes such as the Netherlands Commercial Court and the never-implemented Brussels International Business Court—are the topic of much discussion these days. The NCC is a division of the Dutch courts with Dutch judges. The BIBC proposal, however, envisioned judges who were mostly “part-timers” who may include specialists from outside Belgium. While the BIBC experiment did not pass Parliament, other commercial courts around the world have proliferated, and some hire judges from outside their jurisdictions.

In a new paper forthcoming in the American Journal of International Law, we set out to determine how many members of the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts hire such “traveling judges,” who they are, why they are hired, and why they serve.

Based on new empirical data and interviews with over 25 judges and court personnel, we find that traveling judges are found on commercially focused courts around the world. We identified nine jurisdictions with such courts, in Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Qatar, Kazakhstan, and the Caribbean (the Cayman Islands and the BVI), and The Gambia. These courts are designed to accommodate foreign litigants and transnational litigation—and inevitably, conflicts of laws.

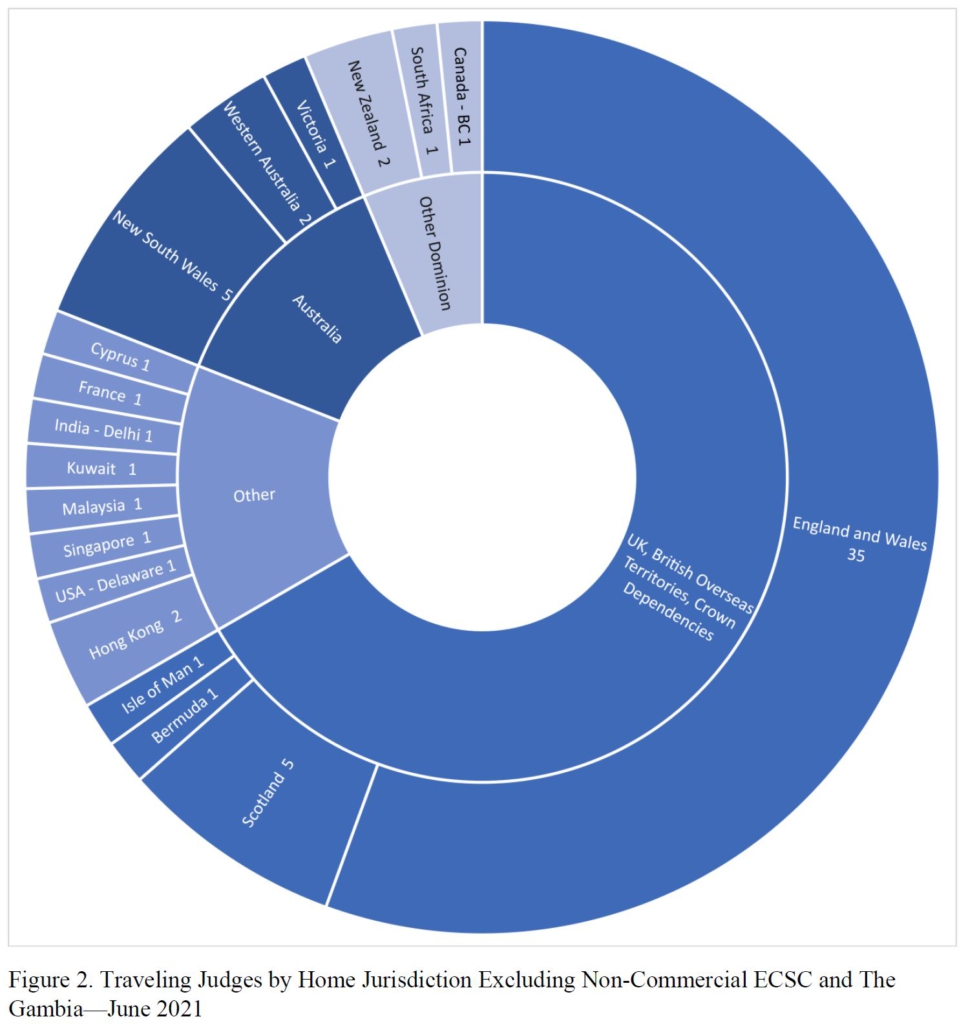

One may assume that these judges largely resemble arbitrators (as was likely intended for the BIBC). But whereas studies show arbitrators are mostly white, male lawyers from “developed” countries that may be based in the common law or civil law tradition, traveling judges are even more likely to be white and male, vastly more likely to have prior judicial experience and common-law legal training, and are overwhelmingly from the UK and its former dominion colonies. In the subset of commercially focused courts in our study, just over half of the traveling judges were from England and Wales specifically. Nearly two-thirds had at least one law degree from a UK university.

Below is a chart showing the home jurisdiction of the judges in our study. This includes traveling judges sitting on the BVI commercial division, Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal, Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) Courts, Qatar International Court, Cayman Islands Financial Services Division, Singapore International Commercial Court, Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Courts, and Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) Courts as of June 2021.

A look at traveling judges’ backgrounds suggests that traveling judges might be a phenomenon limited to common-law countries, but only half of hiring jurisdictions are in common law states. Almost all hiring jurisdictions, however, are common law jurisdictions. Moreover, almost all are or aspire to be market-dominant small jurisdictions (MDSJ). For example, the DIFC Courts are located in a common law jurisdiction within a non-common-law state that has been identified as a MDSJ.

Traveling judges are a phenomenon rooted not only in the rise of international commercial arbitration, but also in the history of the British colonial judicial service. Today, traveling judges may be said to bring their expertise and knowledge of best practices in international commercial dispute resolution. But traveling judges also offer hiring jurisdictions a method of transplanting well-respected courts, like London’s commercial court, on their shores. In doing so, judges reveal these jurisdictions’ efforts to harness business preferences for English common law into their domestic court systems. They also provide further opportunities for convergence on global civil procedure norms, or at least common law ones. Many courts have adopted some version of the English Civil Procedure Rules, looking for something international lawyers find familiar and reliable. Judges also report learning from each other’s approaches.

Our article suggests that traveling judges are a nearly entirely common law phenomenon—only a handful of judges were from mixed jurisdictions and only one was a civil law judge. Common law courts may be especially amenable to traveling judges. In contrast to judges in continental civil law systems, common law judges are not career bureaucrats. They come to the judiciary late, usually after having built successful litigation practices. Moreover, the sociologist, and judge, Antoine Garapon observes that common law style-judging can be more personalized, with more room for individual authority rather than that of the office. All these differences are a matter of degree, with exceptions that come readily to mind. Still, as a result, common law judges are more likely have reputations independent of the office they serve. That reputation, in turn, is valuable to hiring governments eager to demonstrate their commercial law bona fides.

These efforts to harness English common law contrast with the efforts to build international commercial courts in the Netherlands or Belgium. The NCC advertises itself as an English-language court built on the foundation of the Dutch judiciary’s strong reputation. As such, it has no need for foreign judges or common law experience. The BIBC likely also would not have relied as heavily on retired English judges, both because its designers envisioned more lay adjudicators (not retired judges) and likely a greater civil law influence. In that sense, its roster of judges might have more closely resembled that of the new international commercial court in Bahrain.

The Dutch, Belgian, and Bahraini examples do share something else in common with the network of courts profiled in Traveling Judges, however. Despite their apparent similarities to arbitration, these courts are domestic courts, and they exist in significantly different political environments. The differences between Dutch and Belgian national politics influenced the NCC’s success in being established and the BIBC’s failure. In Belgium, for instance, the BIBC was maligned as a “caviar court” for foreign companies and the Belgian Parliament ultimately decided against the proposal. As one of us recounts in a related article on arbitration-court hybrids, similar arguments were raised in the Dutch Parliament, but they did not win the day. Several courts in our study, such as those established in the special economic zones in the UAE, did not face such constraints. But they may face others, such as how local courts will recognize and cooperate with a new court operating according to a different legal system and in a different language. The new court in Bahrain overcame local obstacles to its establishment, but it may face yet another set of political constraints and pressures as it proceeds to hear its first cases. Wherever traveling judges travel, local politics will affect both hiring jurisdictions’ ability to achieve their goals and traveling judges’ ability to judge in the way they are accustomed.