Views

In 2018, the Dutch Supreme Court found a Spanish judgment applicable in the Netherlands, based on the Hague Convention on the International Protection of Adults. Minor detail: neither the Netherlands nor Spain is a party to this Convention.

Written by Dr. Anneloes Kuiper, Assistant Professor at Utrecht University, the Netherlands

In 2018, the Dutch Supreme Court found a Spanish judgment applicable in the Netherlands, based on the Hague Convention on the International Protection of Adults. Minor detail: neither the Netherlands nor Spain is a party to this Convention.

Applicant in this case filed legal claims before a Dutch court of first instance in 2012. In 2013, a Spanish Court put Applicant under ‘tutela’ and appointed her son (and applicant in appeal) as her ‘tutor’. Defendants claimed that, from that moment on, Applicant was incompetent to (further) appeal the case and that the tutor was not (timely) authorized by the Dutch courts to act on Applicant’s behalf. One of the questions before the Supreme Court was whether the decision by the Spanish Court must be acknowledged in the Netherlands.

In its judgment, the Dutch Supreme Court points out that the Convention was signed, but not ratified by the Netherlands. Nevertheless, article 10:115 in the Dutch Civil Code is (already) reserved for the application of the Convention. Furthermore, the Secretary of the Department of Justice has explained that the reasons for not ratifying the Convention are of a financial nature: execution of the Convention requires time and resources, while encouraging the ‘anticipatory application’ of the HCIPA seems to be working just as well. Because legislator and government seem to support the (anticipatory) application of the Convention, the Supreme Court does as well and, for the same reasons, has no objection to applying the Convention when the State whose ruling is under discussion is not a party to the treaty either (i.e. Spain).

This ‘anticipatory application’ was – although as such unknown in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties – used before in the Netherlands. While in 1986 the Rome Convention was not yet into force, the Dutch Supreme Court applied article 4 Rome Convention in an anticipatory way to determine the applicable law in a French-Dutch purchase-agreement. In this case, the Supreme Court established two criteria for anticipatory application, presuming it concerns a multilateral treaty with the purpose of establishing uniform rules of international private law:

- No essential difference exists between the international treaty rule and the customary law that has been developed under Dutch law;

- the treaty is to be expected to come into force in the near future.

In 2018, the Supreme Court seems to follow these criteria. These criteria have pro’s and con’s, I’ll name one of each. The application of a signed international treaty is off course to be encouraged, and the Vienna Convention states that after signature, no actions should be taken that go against the subject and purpose of the treaty. Problem is, if every State applies a treaty ‘anticipatory’ in a way that is not too much different from its own national law – criterion 1 – the treaty will be applied in as many different ways as there are States party to it. Should it take some time before the treaty comes into force, there won’t be much ‘uniform rules’ left.

The decision ECLI:NL:HR:2018:147 (in Dutch) is available here.

The Netherlands Commercial Court holds its first hearing!

Written by Georgia Antonopoulou and Xandra Kramer, Erasmus University Rotterdam (PhD candidate and PI ERC consolidator project Building EU Civil Justice)

Only six weeks after its establishment, the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC) held its first hearing today, 18 February 2019 (see our previous post on the creation of the NCC). The NCC’s maiden case Elavon Financial Services DAC v. IPS Holding B.V. and others was heard in summary proceedings and concerned an application for court permission to sell pledged shares (see here). The application was filed on 11 February and the NCC set the hearing date one week later, thereby demonstrating its commitment to offer a fast and efficient forum for international commercial disputes.

The parties’ contract entailed a choice of forum clause in favour of the court in Amsterdam. However, according to the new Article 30r (1) of the Dutch Code of Civil Procedure and Article 1.3.1. of the NCC Rules an action may be initiated in the NCC if the Amsterdam District Court has jurisdiction to hear the action and the parties have expressly agreed in writing to litigate in English before the NCC. Lacking an agreement in the initial contract, the parties in Elavon Financial Services DAC v. IPS Holding B.V. subsequently agreed by separate agreement to bring their case before the newly established chamber and thus to litigate in English, bearing the NCC’s much higher, when compared to the regular Dutch courts, fees. Unlike other international commercial courts which during their first years of functioning were ‘fed’ with cases transferred from other domestic courts or chambers, the fact that the parties in the present case directly chose the NCC is a positive sign for the court’s future case flow.

As we have reported on this blog before, the NCC is a specialized chamber of the Amsterdam District Court, established on 1 January 2019. It has jurisdiction in international civil and commercial disputes, on the basis of a choice of court agreement. The entire proceedings are in English, including the pronouncement of the judgment. Judges have been selected from the Netherlands on the basis of their extensive experience with international commercial cases and English language skills. The Netherlands Commercial Court of Appeal (NCCA) complements the NCC on appeal. Information on the NCC, a presentation of the court and the Rules of Procedure are available on the website of the Dutch judiciary. It advertises the court well, referring to “the reputation of the Dutch judiciary, which is ranked among the most efficient, reliable and transparent worldwide. And the Netherlands – and Amsterdam in particular – are a prime location for business, and a gateway to Europe.” Since a number of years, the Dutch civil justice system has been ranked no. 1 in the WJP Rule of Law Index.

In part triggered by the uncertainties of Brexit and the impact this may have on the enforcement of English judgments in Europe in particular, more and more EU Member States have established or are about to establish international commercial courts with a view to accommodating and attracting high-value commercial disputes (see also our previous posts here and here). Notable similar initiatives in Europe are the ‘Frankfurt Justice Initiative’ (for previous posts see here and here) and the Brussels International Business Court (see here). While international commercial courts are mushrooming in Europe, a proposal for a European Commercial Court has also come to the fore so as to effectively compete with similar courts outside Europe (see here and here).

The complexity of the post Brexit era for English LLPs and foreign legal professionals in EU Member States: a French perspective

Written by Sophie Hunter, University of London (SOAS)

In light of the turmoil in the UK Parliament since the start of 2019, the only certain thing about Brexit is that everything is uncertain. The Law Society of England and Wales has warned that “if the UK’s relationship with the rest of the EU were to change as the result of significant renegotiations, or the UK choosing to give up its membership, the effects would be felt throughout the legal profession.” As a result of Brexit, British firms and professionals will no longer be subject to European directives anymore. This foreshadows a great deal of complexity. Since British legal entities occupy a central place within the European legal market, stakes are high for both British and European lawyers. A quick overview of the challenges faced by English LLPs in France and the Paris Bar demonstrates a high level of complexity that, is not and, should be considered more carefully by politicians. Read more

News

PhD Studentship in Private International Law at University College London

Written by Ugljesa Grusic, Associate Professor at University College London, Faculty of Laws

Dr Ugljesa Grusic and Prof Alex Mills are pleased to announce that, alongside the UCL Faculty of Laws Research Scholarships which are open to all research areas, this year we have an additional scholarship specifically for doctoral research in private international law. The scholarship covers the cost of tuition fees (home status fees) and provides a maintenance stipend per annum for full time study at the standard UKRI rate. The annual stipend for 2023/24 (as a guide) was £20,622. The recipient of the scholarship will be expected to contribute to teaching private international law in the Faculty for up to 6 hours per week on average, and this work is remunerated in addition to the stipend received for the scholarship.

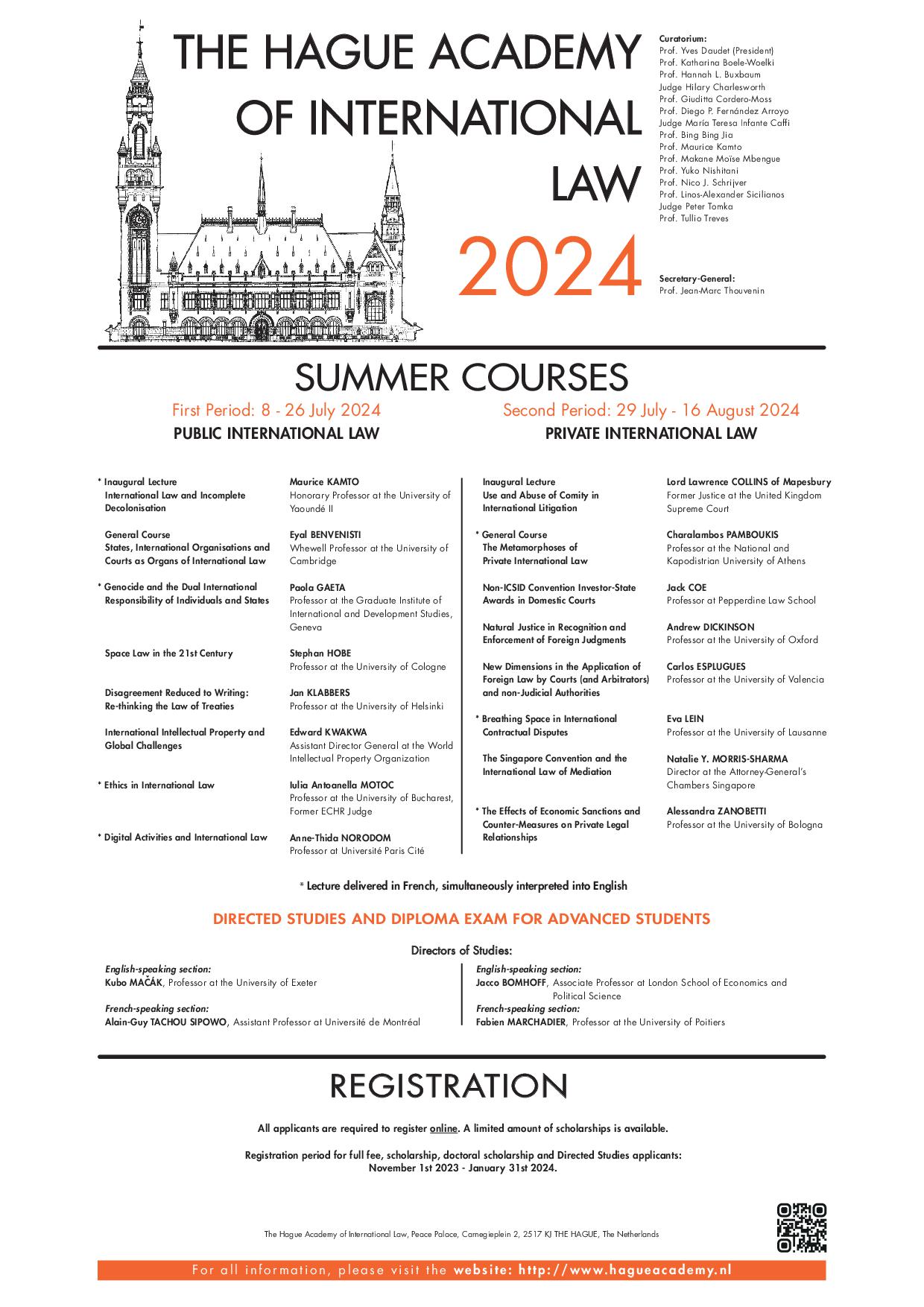

Out Now: Programme of the Hague Academy of International Law’s Summer Courses 2024

Asian Private International Law Academy Conference 2023 on 9 and 10 December

The Asian Private International Law Academy (APILA) will be holding its second conference at Doshisha University, Kyoto, on 9 and 10 December 2023. The keynote addresses will be delivered by Professor Emerita Linda Silberman on 9 December and Professor Gerald Goldstein on 10 December. The first day of the conference will comprise presentation and discussion of works-in-progress. The conference will devote most of 10 December to discussion and finalisation of the Asian Principles on Private International Law (APPIL) on three topics: (1) recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments, (2) direct jurisdiction, and (3) general choice of law rules. Persons interested in attending or wishing further information should email reyes.anselmo@gmail.com to that effect. Please note that, while APILA can assist attendees by issuing letters of invitations in support of Japanese visa applications, APILA’s available funding is limited. In the normal course of events, APILA regrets that it will not be able to provide funding for travel and accommodation expenses.