Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Conflict of Laws

by Tobias Lutzi, University of Cologne

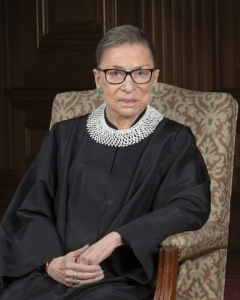

Since the sad news of her passing, lawyers all around the world have mourned the loss of one of the most iconic and influential members of the legal profession and a true champion of gender equality. Through her work as a scholar and a justice, just as much as through her personal struggles and achievements, Ruth Bader Ginsburg has inspired generations of lawyers.

On top of being a global icon of women’s rights and a highly influential voice on a wide range of issues, Ginsburg has also expressed her views on questions relating to the interaction between different legal systems, both within the US and internationally, on several occasions. In fact, two of her early law-review articles focus entirely on two perennial problems of private international law.

On top of being a global icon of women’s rights and a highly influential voice on a wide range of issues, Ginsburg has also expressed her views on questions relating to the interaction between different legal systems, both within the US and internationally, on several occasions. In fact, two of her early law-review articles focus entirely on two perennial problems of private international law.

Accordingly, readers of this blog may enjoy to go through some of her writings in this area, both judicial and extra-judicial, in an attempt to pay tribute to her work.

Jurisdiction

In one of Ginsburg’s earliest publications, The Competent Court in Private International Law: Some Observations on Current Views in the United States (20 (1965) Rutgers Law Review 89), she retraces the approach to the adjudication of persons outside the forum state in US law by reference to both the common law and continental European approaches. She argues that

[t]he law in the United States has […] moved closer to the continental approach to the extent that a relationship between the defendant or the particular litigation and the forum, rather than personal service, may function as the basis of the court’s adjudicatory authority.

Ginsburg points out, though, that each approach includes ‘exorbitant’ bases of judicial competence, which ‘provide for adjudication resulting in a personal judgment in cases in which there may be no connection of substance between the litigation and the forum state.’

Bases of judicial competence found in the internal laws of certain continental states, but generally considered undesirable in the international sphere, include competence founded exclusively on the nationality of the plaintiff – for example, Article 14 of the French Civil Code – and competence (to render a personal judgment) based on the mere presence of an asset of the defendant when the claim has no connection with that asset-a basis found in the procedural codes of Germany, Austria, and the Scandinavian countries. Equally undesirable in the view of continental jurists is the traditional Anglo-American rule that personal service within the territory of the forum confers adjudicatory authority upon a court even in the case of a defendant having no contact with the forum other than transience

The ‘most promising currently feasible remedy’ for improper use of these ‘internationally undesirable’ bases of jurisdiction, she argues, is the doctrine of forum non conveniens.

At the least, a plaintiff who chooses such a forum should be required to show some reasonable justification for his institution of the action in the forum state rather than in a state with which the defendant or the res, act or event in suit is more significantly connected.

Applicable Law

As a Supreme Court justice, Ginsburg also had numerous opportunities to rule on conflicts between federal and state law.

In Honda Motor Co v Oberg (512 U.S. 415 (1994)), for instance, Ginsburg dissented from the Court’s decision that an amendment to the Oregon Constitution that prevented review of a punitive-damage award violated the Due Process Clause of the federal Constitution, referring to other protections against excessive punitive-damage awards in Oregon law. In BMW of North America, Inc v Gore (517 US 559 (1996)), she dissented from another decision reviewing an allegedly excessive punitive-damages award and argued that the Court should ‘resist unnecessary intrusion into an area dominantly of state concern.’

According to Paul Schiff Berman (who provided a much more complete account of Ginsburg’s relevant writings than this post can offer in Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Interaction of Legal Systems (in Dodson (ed), The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (CUP 2015) 151)), her ‘willingness to defer to state prerogatives in interpreting state law […] may surprise those who focus on Justice Ginsburg’s Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence in gender-related cases.’

The same deference can also be found in some of her writings on the interplay between US law and other legal systems, though. In a speech to the International Academy of Comparative Law, she argued in favour of taking foreign and international experiences into account when interpreting US law and concluded:

Recognizing that forecasts are risky, I nonetheless believe the US Supreme Court will continue to accord “a decent Respect to the Opinions of [Human]kind” as a matter of comity and in a spirit of humility. Comity, because projects vital to our well being […] require trust and cooperation of nations the world over. And humility because, in Justice O’Connor’s words: “Other legal systems continue to innovate, to experiment, and to find . . . solutions to the new legal problems that arise each day, [solutions] from which we can learn and benefit.”

Recognition of Judgments

Going back to another one of Ginsburg’s early publications, in Judgments in Search of Full Faith and Credit: The Last-in-Time Rule for Conflicting Judgments (82 (1969) Harvard Law Review 798), Ginsburg discussed the problem of the hierarchy between conflicting judgments from different states and made a case for ‘the unifying function of the full faith and credit clause’. As to whether anti-suit injunctions should also the clause, she expressed a more nuanced view, though, explaining that

[t]he current state of the law, permitting the injunction to issue but not compelling any deference outside the rendering state, may be the most reasonable compromise […].

The thesis of this article, that the national full faith and credit policy should override the local interest of the enjoining state, would leave to the injunction a limited office. It would operate simply to notify the state in which litigation has been instituted of the enjoining state’s appraisal of forum conveniens. That appraisal, if sound, might induce respect for the injunction as a matter of comity.

Ginsburg had an opportunity to revisit a similar question about thirty years later, when delivering the opinion of the Court in Baker v General Motor Corp (522 US 222 (1998)). Although the Full Faith and Credit Clause was not subject to a public-policy exception (as held by the District Court), an injunction stipulated in settlement of a case in front of a Michigan court could not prevent a Missouri court from hearing a witness in completely unrelated proceedings:

Michigan lacks authority to control courts elsewhere by precluding them, in actions brought by strangers to the Michigan litigation, from determining for themselves what witnesses are competent to testify and what evidence is relevant and admissible in their search for the truth.

This conclusion creates no general exception to the full faith and credit command, and surely does not permit a State to refuse to honor a sister state judgment based on the forum’s choice of law or policy preferences. Rather, we simply recognize that, just as the mechanisms for enforcing a judgment do not travel with the judgment itself for purposes of Full Faith and Credit […] and just as one State’s judgment cannot automatically transfer title to land in another State […] similarly the Michigan decree cannot determine evidentiary issues in a lawsuit brought by parties who were not subject to the jurisdiction of the Michigan court.

According to Berman, this line of reasoning is testimony to Ginsburg’s judicial vision of ‘a system in which courts respect each other’s authority and judgments.’

—

The above selection has been created rather spontaneously and is evidently far from complete; please feel free to use the comment section to highlight other interesting parts of Justice Ginsburg’s work.

This year Justice Ginsburg also delivered the opinion of the US Supreme Court in the case Monasky v. Taglieri 589 U.S. __ (2020) regarding the habitual residence of the child in child abduction matters. A truly great decision.

Among other things, she states:

The understanding that the opinions of our sister signatories to a treaty are due “considerable weight,” this Court has said, has “special force” in Hague Convention cases. Ibid. (quoting El Al Israel Airlines, Ltd. v. Tsui Yuan Tseng, 525 U. S. 155, 176 (1999), in turn quoting Air France, 470 U. S., at 404). The “clear trend” among our treaty partners is to treat the determination of habitual residence as a fact-driven inquiry into the particular circumstances of the case. Balev, [2018] 1 S. C. R., at 423, ¶50, 424 D. L. R. (4th), at 411, ¶50.

Thanks Tobias (and Mayela), this is great. Interestingly, Justice Ginsburg worked very closely with the great Herma Hill Kay in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in the area of sex discrimination.