Views

A Boost in the Number of European Small Claims Procedures before Spanish Courts: A Collateral Effect of the Massive Number of Applications for European Payment Orders?

Carlos Santaló Goris, Researcher at the Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Luxembourg, offers an analysis of the Spanish statistics on the European Small Claims Procedure.

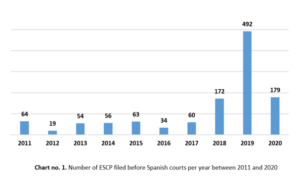

Until 2017, the annual number of European Small Claims Proceedings (“ESCP”) in Spain was relatively small, with an average of 50 ESCPs per year. With some exceptions, this minimal use of the ESCP fits the general trend across Europe (Deloitte Report). However, from 2017 to 2018 the number of ESCPs in Spain increased 286,6%. Against the 60 ESCPs issued in 2017, 172 were issued in 2020. In 2019, the number of ESCPs continued climbing to 492 ESCPs. This trend reversed in 2020, when there were just 179 ESCPs.

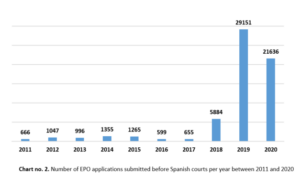

The use of the Regulation establishing the European Payment Order (“EPO Regulation”) experienced a similar fluctuation between 2018 and 2020. Since its entry into force, the EPO Regulation was significantly more prevalent among Spanish creditors than the ESCP Regulation. Between 2011 to 2020, there were an average of 940 EPO applications per year. Nonetheless, from 2017 to 2019, the number of EPO applications increased 4.451%: just in 2019, 29,151 EPOs were issued in Spain. In 2020, the number of EPOs decreased to 21,636. the massive boost in EPO applications results from creditors’ attempts to circumvent EU consumer protection standards under the Spanish domestic payment order.

From Banco Español de Crédito to Bondora

After the CJEU judgment C-618/10, Banco Español de Crédito, the Spanish legislator amended the Spanish Code of Civil Procedure to impose on courts a mandatory review of the fairness of the contractual terms in a request for a domestic payment order. Creditors noticed that they could circumvent such control through the EPO. Unlike the Spanish payment order, the EPO is a non-documentary type payment order. For an EPO, standard form creditors only have to indicate “the cause of the action, including a description of the circumstances invoked as the basis of the claim” as well as “a description of evidence supporting the claim” (Article 7(2) EPO Regulation). Moreover, the Spanish legislation implementing the EPO states that courts have to reject any other documentation beyond the EPO application standard form. Creditors realized that in this manner there was no possible way for the court to examine the fairness of the contratual terms in EPOs against consumers. Consequently, the number of EPO applications between 2017 and 2019 increased remarkably.

In some cases, a claim’s cross-border dimension was even fabricated to access the EPO Regulation. The EPO, like the ESCP, is only applicable in cross-border claims, which means that “at least one of the parties is domiciled or habitually resident in a Member State other than the Member State of the court seised”(Article 3 EPO Regulation). Against this background, creditors assigned the debt to a creditor abroad (in many cases, vulture funds and companies specialized in debt recovery) in order to transform a purely internal claim into a cross-border one.

The abnormal increase in the number of EPOs did not go unnoticed among Spanish judges. Three Spanish courts decided to submit preliminary references to the CJEU, asking, precisely, whether it is possible to examine the fairness of the contractual terms in an EPO application requested against a consumer. Two of these preliminary references led to the judgment Joined Cases C?453/18 and C?494/18, Bondora, where the CJEU replied positively, acknowledging that courts can examine the fairness of the contractual terms (on this judgment, see this previous post). The judgment was rendered in December 2019. In 2020, the number of EPOs started to decrease. It appears that after Bondora the EPO became less attractive to creditors.

The connection between the EPO and the ESCP Regulation

At this point one needs to ask how the increase in the use of the EPO Regulation has had an impact on the use of the ESCP Regulation. The answer is likely found in the 2015 joint reform of the EPO and ESCP Regulations (Regulation (EU) 2015/2421). Among other changes, this reform introduced an amendment in the EPO Regulation which allows, once the creditor lodges a statement of opposition against an EPO, for an automatic continuation of proceedings under the ESCP (Article 17(1)(a) EPO Regulation). For this to happen, creditors simply need to state their intention by making use of a code in the EPO application standard form. It appears that, in Spain, many of those creditors who applied for an EPO in order to circumvent consumer protection standards under the domestic payment order found in the ESCP a subsdiary proceeding if debtors opposed the EPO.

An isolated Spanish phenomenon?

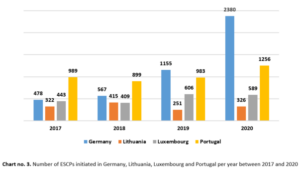

Statistics in Spain show that, at least in this Member State, the connection between the EPO and ESCP Regulations functions and gives more visibility to the ESCP. The lack of awareness about the ESCP Regulation was one of the issues that the Commission aimed to tackle with the 2015 reform. One might wonder if a similar increase in the use of the ESCP could be appreciated in other Member States. Available public statistics in Portugal, Lithuania, and Luxembourg do not reveal any significant change in the use of the ESCP after 2017, the year the amendment entered into force. In Lithuania, the number of ESCPs even decreased from 2018 to 2019.

Conversely, in Germany, statistics reveal a steady growth over those years. Against the 478 ESCPs issued in Germany in 2017, 2380 ESCP were issued in 2020, standing for an increase of 498%. Perhaps, after an unsuccessful start, the ESCP Regulation is finally bearing fruit.

ECJ, judgment of 10 February 2022, Case 522/20 – OE ./. VY, on the validity of the connecting factor „nationality“ in the Brussels IIbis Regulation (2201/2003) in light of Article 18 TFEU.

Today, in the case of OE ./. VY, C-522/20 (no Opinion was delivered in these proceedings), the ECJ decided on a fundamental point: whether nationality as a (supplemental) connecting factor for jurisdiction according to Article 3 lit. a indent 6 of the Brussels IIbis Regulation (2201/2003) concerning jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and the matters of parental responsibility is in conformity with the principal prohibition of discrimination against nationality in the primary law of the European Union (Art. 18 TFEU).

Article 18 TFEU reads: “Within the scope of application of the Treaties, and without prejudice to any special provisions contained therein, any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited. …”.

Art. 3 lit. a Brussels IIbis Regulation reads: “In matters relating to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment, jurisdiction shall lie with with the courts of the Member State:”; indent 5 reads: “in whose territory the applicant is habitually resident if he or she resided there for at least a year immediately before the application was made, or”, according to indent 6: “the applicant is habitually resident if he or she resided there for at least six months immediately before the application was made and is either a national of the Member State in question …”.

The case emerged from a request in proceedings between OE and his wife, VY, concerning an application for dissolution of their marriage brought before the Austrian courts (paras. 9 et seq.):

“On 9 November 2011, OE, an Italian national, and VY, a German national, were married in Dublin (Ireland). According to the information provided by the referring court, OE left the habitual residence the couple shared in Ireland in May 2018 and has lived in Austria since August 2019. On 28 February 2020, that is, after residing in Austria for more than six months, OE applied to the Bezirksgericht Döbling (District Court, Döbling, Austria) for the dissolution of his marriage with VY. OE submits that a national of a Member State other than the State of the forum is entitled to invoke the jurisdiction of the courts of that latter State under the sixth indent of Article 3(1)(a) of Regulation No 2201/2003, on the basis of observance of the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of nationality, after having resided in the territory of that latter State for only six months immediately before making the application for divorce, which is tantamount to disregarding the application of the fifth indent of that provision, which requires a period of residence of at least a year immediately before the application for divorce is made. By order of 20 April 2020, the Bezirksgericht Döbling (District Court, Döbling) dismissed OE’s application, taking the view that it lacked jurisdiction to hear it. According to that court, the distinction made on the basis of nationality in the fifth and sixth indents of Article 3(1)(a) of Regulation No 2201/2003 is intended to prevent the applicant from forum shopping. By order of 29 June 2020, the Landesgericht für Zivilrechtssachen Wien (Regional Court for Civil Matters, Vienna, Austria), hearing the case on appeal, upheld the order of the Bezirksgericht Döbling (District Court, Döbling). OE brought an appeal on a point of law against that order before the referring court, the Oberster Gerichtshof (Supreme Court, Austria).”

The Court reiterated, inter alia, that (paras. 18 et seq.) the principle of non-discrimination and equal treatment require that comparable situations must not be treated differently and different situations must not be treated in the same way, “unless such treatment is objectively justified”, further that the comparability of different situations must be assessed having regard to all the elements which characterise them, and thirdly that the (EU) legislature has a broad discretion in this respect. “Thus, only if a measure adopted in this field is manifestly inappropriate in relation to the objectives which the competent institutions are seeking to pursue can the lawfulness of such a measure be affected”.

Against this background the Court held (paras 25 et seq.) that, first, Article 3 meets “the need for rules that address the specific requirements of conflicts relating to the dissolution of matrimonial ties”, secondly that while the first to fourth indents of Article 3(1)(a) of Regulation expressly refer to the habitual residence of the spouses and of the respondent as criteria, the fifth and sixth indents of Article 3(1)(a) permit the application of the jurisdiction rules of the forum actoris, and thirdly that “it is apparent from the Court’s case-law that the rules on jurisdiction laid down in Article 3 of Regulation No 2201/2003, including those laid down in the fifth and sixth indents of paragraph 1(a) of that article, seek to ensure a balance between, on the one hand, the mobility of individuals within the European Union, in particular by protecting the rights of the spouse who, after the marriage has broken down, has left the Member State where the couple had their shared residence and, on the other hand, legal certainty, in particular that of the other spouse, by ensuring that there is a real link between the applicant and the Member State whose courts have jurisdiction to give a ruling on the dissolution of the matrimonial ties concerned (see, to that effect, judgments of 13 October 2016, Mikolajczyk, C-294/15, EU:C:2016:772, paragraphs 33, 49 and 50, and of 25 November 2021, IB (Habitual residence of a spouse – Divorce), C-289/20, EU:C:2021:955, paragraphs 35, 44 and 56).“ And the fact that typically there is such a real link if there is nationality sufficed to justify distinguishing between indent 5 and indent 6, all the more as this cannot be a surprise to the other spouse.

Therefore the Court came to the conclusion:

“The principle of non-discrimination on grounds of nationality, enshrined in Article 18 TFEU, must be interpreted as not precluding a situation in which the jurisdiction of the courts of the Member State in the territory of which the habitual residence of the applicant is located, as provided for in the sixth indent of Article 3(1)(a) of Council Regulation (EC) No 2201/2003 of 27 November 2003 concerning jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and the matters of parental responsibility, repealing Regulation (EC) No 1347/2000, is subject to the applicant being resident for a minimum period immediately before making his or her application which is six months shorter than that provided for in the fifth indent of Article 3(1)(a) of that regulation on the ground that the person concerned is a national of that Member State.”

The most important take away seems to be that PIL legislation using nationality as a supplemental connnecting factor is still in conformity with Article 18 TFEU as long as it appears “not manifestly inappropriate” (para. 36). Therefore, and reconnecting to older case law (para. 39), legislation is still valid “with regard to a criterion based on the nationality of the person concerned, … although in borderline cases occasional problems must arise from the introduction of any general and abstract system of rules” so that “there are no grounds for taking exception to the fact that the EU legislature has resorted to categorisation, provided that it is not in essence discriminatory having regard to the objective which it pursues (see, by analogy, judgments of 16 October 1980, Hochstrass v Court of Justice, 147/79, EU:C:1980:238, paragraph 14, and of 15 April 2010, Gualtieri v Commission, C-485/08 P, EU:C:2010:188, paragraph 81).”

A Reform of French Law Inspired by an Inaccurate Interpretation of the EAPO Regulation?

Carlos Santaló Goris, Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Luxembourg, offers an analysis on the recently approved reform of the French Manual on Tax Procedures (“Livre des procédures fiscales”) influenced by Regulation No 655/2014, establishing a European Account Preservation Order (“EAPO Regulation”). The EAPO Regulation and other EU civil procedural instruments are the object of study in the ongoing EFFORTS project, with the financial support of the European Commission.

FICOBA (“Fichier national des comptes bancaires et assimilés”) is the French national register containing information about all the bank accounts in France. French bailiffs (“huissiers”) can rely on FICOBA to to facilitate the enforcement of an enforceable title or upon a request for information in the context of an EAPO proceeding (Article L151 A of the French Manual on Tax Procedures). In January 2021, the Paris Court of Appeal found discriminatory the fact that creditors could obtain FICOBA information in the context of an EAPO proceeding but not in the context of the equivalent French domestic provisional attachment order, the “saisie conservatoire” (for a more extended analysis of the judgment, see here). While an enforceable title is not a necessary precondition to access FICOBA in the context of an EAPO, under French domestic law it is. Against this background, the French court found that creditors who could apply for an EAPO were in a more advantageous position than those who could not. Consequently, it decided to extend access to FICOBA to creditors without an enforceable title who apply for a saisie conservatoire.

In December 2021, the judgment rendered by the Paris Court of Appeals was transposed into French law. In fact, the French legislator introduced an amendment to the French Manual on Tax Procedures, allowing bailiffs to collect information about the debtors’ bank accounts from FICOBA based on a saisie conservatoire (Art. 58 LOI n° 2021-1729 du 22 décembre 2021 pour la confiance dans l’institution judiciaire).

In is nevertheless noteworthy that the judgment of the Paris Court of Appeal that inspired such reform is based on a misinterpretation of the EAPO Regulation. Access to the EAPO Regulation’s information mechanism is limited to creditors with a title (either enforceable or not enforceable). Creditors without a title are barred from accessing the EAPO’s information mechanism. From the reasoning of the Paris Court of Appeal, it appears that the Court interpreted the EAPO Regulation as granting access to the EAPO’s information mechanism to all creditors, even to those without a title. Such an interpretation would have been in accordance with the EAPO Commission Proposal, which gave all creditors access to the information mechanism regardless of whether they had a title or not. However, the Commission’s open approach was received with scepticism by the Council and some Member States. Notably, France was the most vocal advocate of limiting the possibilities of relying on the EAPO information mechanism. It considered that only creditors with an enforceable title should have access to it. In particular, the French delegation argued that, under French law, only creditors with an enforceable title could access such sensitive data about the debtor. Eventually the European legislator decided to adopt a mid-way solution between the French position and the EAPO Commission Proposal: namely, in accordance with the Regulation creditors are required to have a title, though this does not have to be enforceable.

The following is an interesting paradox. Whereas France tried to adjust the EAPO’s information mechanism to the standards of French law, it was ultimately French law that was amended due to the influence of the EAPO Regulation. An additional paradox is that the imbalance between creditors who can access the EAPO Regulation and those who cannot (as emphasized and criticised by the Paris Court of Appeal) will continue to exist but with the order reversed. Once the French reform enters into force, creditors without a title who apply for a French saisie conservatoire of a bank account will be given access to FICOBA. Conversely, creditors who apply for an EAPO will continue to be required to have a title in order to access FICOBA. Only an amendment of the EAPO Regulation can change this.

The moment for considering a reform of the EAPO Regulation is approaching. In accordance with Article 53 of the EAPO Regulation, the European Commission should have sent to the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee “a report on the application of this Regulation” by 18 January 2022. These reports should serve as a foundation to decide whether amendments to the EAPO Regulation are desirable. Perhaps, as a result of the experience offered with the judgment of the Paris Court of Appeal, the European legislator may consider extending the EAPO’s information mechanism beyond creditors with a title.

News

Dutch Journal of PIL (NIPR) – issue 2024/2

The latest issue of the Dutch Journal on Private International Law (NIPR) has been published.

NIPR 2024 issue 2

EDITORIAL

M.H. ten Wolde / p. 239

Article

C.G. van der Plas, A.F. Veldhuis, B.H.B. Verheul, Automatische erkenning en tenuitvoerlegging van vonnissen in het Europa van nu: de noodzaak van een nieuwe blik op wederzijds vertrouwen na J/H Limited / p. 241-267 Read more

Out now: The Korean Journal of International and Comparative Law, Volume 12 (2024), Issue 1

The following information has been kindly provided by Wilson Lui, PhD Candidate, Melbourne Law School; Part-time Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong.

The latest issue of the Journal is available online and features the following papers delivered at the ILA-Korea’s 60th Anniversary Conference on Private International Law held in Seoul, Korea on 11 June 2024:

Call for Papers: 3rd Asian Private International Law Academy Conference (8th to 9th December 2024)

The following information has kindly been provided by Anselmo Reyes.

The third Asian Private International Law Academy (APILA) Conference will take place in person at Thammasat University in Bangkok, Thailand on Sunday 8 (Day 1) and Monday 9 (Day 2) December 2024. Persons whose abstracts have been selected (see next paragraph) will deliver oral presentations in turn on Days 1 and 2. Each presentation will run for about 10 minutes and be followed by a discussion of about 10 to 15 minutes in which participants will have the opportunity to comment on a presentation. The APILA Conference will be in the form of two days of roundtable discussions in English. The objective of the APILA Conference is to assist presenters to refine prospective research papers with a view to eventual publication. Read more