Views

Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

News

II Jean Monnet Network – BRIDGE Seminar “Migration and Citizenship in the European Union and Latin America”

by Aline Beltrame de Moura, Professor at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, in Brazil

On November 9, 2021, at 4 pm (BR time – GMT -03:00), the Faculty of Law of the Federal University of Santa Catarina will hold a virtual conference, called II Jean Monnet Network Seminar – BRIDGE “Migration and Citizenship in the European Union and Latin America”.

Participants in the event include the Member of the European Parliament, Margarida Marques; the Deputy Head of the European Union Delegation in Brazil, Ana Beatriz Martins; the Regional Policy and Coordination Officer of the International Organization for Migration (IOM – South America), Ezequiel Texidó; the Deputy Representative of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Brazil, Federico Martinez; the Immigration Legal Adviser of Unión Sindical Obrera in Spain, Max Adam Romero; and former employee of Argentina’s Dirección de Migraciones and professor at the Universidad Abierta Interamericana, Emiliano Bursese.

In addition to the Seminar, the event will also feature the presentation of sixteen articles selected through Call for Papers. The two best articles will be awarded the value of EUR 250 each. The Workshop presentations will take place on November 9 from 8:40 am to 12:00 pm (BR time – GMT -03:00), in a virtual mode.

The conference is part of the Jean Monnet Network project called “Building Rights and Developing Knowledge between European Union and Latin America – BRIDGE”, which is part of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil); the Faculty of Law of the University of Lisbon; the University of Seville (Spain); the University of Milan (Italy); the National Autonomous University (Mexico); the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina) and the University of Rosario (Colombia).

The seminar will be held in Portuguese and Spanish. Registration is free and must be made through the link https://www.even3.com.br/2seminariobridge

Check out the full schedule at: https://eurolatinstudies.com/laces/announcement/view/85

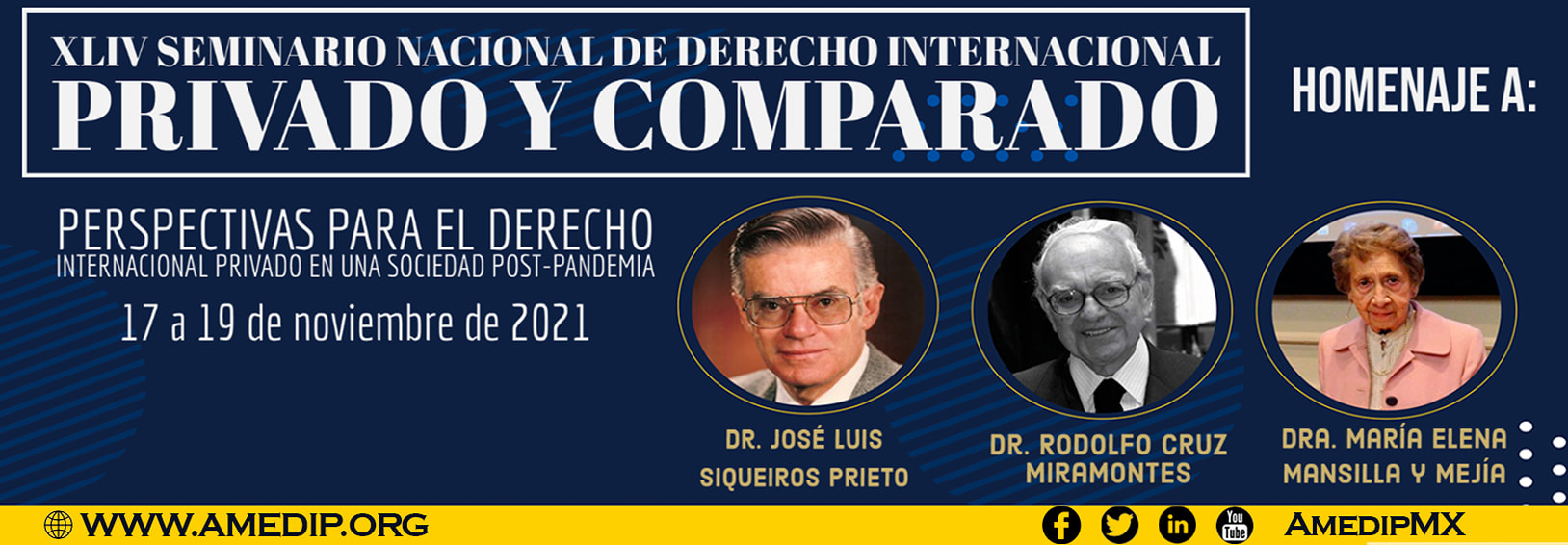

AMEDIP: The programme of the XLIV Seminar is now available

The programme of the XLIV Seminar of the Mexican Academy of Private International and Comparative Law (AMEDIP) is now available here. As previously announced, the XLIV Seminar will take place online from 17 to 19 November 2021.

During this seminar, AMEDIP will pay tribute to the late Mexican professors José Luis Siqueiros Prieto, Rodolfo Cruz Miramontes and María Elena Mansilla y Mejía. Professors Siqueiros Prieto and Mansilla y Mejía were deeply involved in the negotiations – at different stages – of the HCCH Judgments Project and the HCCH 2005 Choice of Court Convention, among other international and regional Conventions.

Among the topics to be discussed are the impact of the pandemic on international family law, legal aspects surrounding vaccines, human rights and private international law, international contracts, arbitration and other selected topics. Speakers come from several Latin American States and a few from Europe: Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, the Netherlands, Peru, Spain and Uruguay.

Participation is free of charge. The language of the seminar will be Spanish.

The meeting will be held via Zoom. The access details are the following:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/5554563931?pwd=WE9uemJpeWpXQUo1elRPVjRMV0tvdz09

Meeting ID: 555 456 3931

Password: 00000

For more information, see AMEDIP’s website and its Facebook page

Lex & Forum: Third issue – A special on the limits of private autonomy in the EU

The third issue of the Lex & Forum is dedicated to the topic of the limits of private autonomy in the EU. The preface was prepared by Professor Emeritus and President of the International Hellenic University Athanassios Kaissis. The central topic of the present issue (Focus) is further elaborated by the contributions of Professor Spyros Tsantinis on the importance of private autonomy in European and international procedural law, and of Dr. Konstantinos Voulgarakis on the protection mechanisms in the case of choice of court agreements. Furthermore, Dr. Stefanos Karameros is analyzing the extension of the choice of court agreements in case of privies in law or privies in blood, after the Kauno Miesto decision.

The third issue of the Lex & Forum is dedicated to the topic of the limits of private autonomy in the EU. The preface was prepared by Professor Emeritus and President of the International Hellenic University Athanassios Kaissis. The central topic of the present issue (Focus) is further elaborated by the contributions of Professor Spyros Tsantinis on the importance of private autonomy in European and international procedural law, and of Dr. Konstantinos Voulgarakis on the protection mechanisms in the case of choice of court agreements. Furthermore, Dr. Stefanos Karameros is analyzing the extension of the choice of court agreements in case of privies in law or privies in blood, after the Kauno Miesto decision.

The Focus of this issue is further enriched by the contributions of Judge Dimitrios Titsias on private autonomy in family law, and of Judge Antonios Vathrakokoilis on the choice of applicable law by the diseased according to the EU Regulation No 650/2012. The Focus also contains the analysis of Professor Komninos Komnios on the execution of judgments on investment arbitration within the EU after the Achmea case and the examination of Dr. Nikolaos Zaprianos on the applicable law in online consumer disputes.

The Focus is further enriched by selected case law and, amongst others, the judgment No 362/2020 of the Herakleion Court of First Instance on the subjection of hotel contract cases under the exclusive jurisdiction of immovable property, with a case note by Anastasia Kalantzi, the judgment No 13.2.2020, n. 3561 by the Italian Cassazione Civile (S.U.), on the relationship between the provisions of the Montreal Convention and a prorogation agreement in case of airplane transport, with a case note by Judge Ioannis Valmantonis, and the case 3 Ob 127-20b of the Oberster Gerichtshof on the scenario of parallel non-exclusive prorogation and arbitration clauses, with a case note by Dr. Ioannis Revolidis. Finally, the Focus is concluded by Dr. Apostolos Anthimos’s case note on the Greek Supreme Court (Areios Pagos) judgment No 767/2019, regarding the execution of an American judgment that lost its validity domestically.

The scientific topics of the present issue consist of the contribution of Professor Paris Arvanitakis on the issue of asymmetrical choice of court agreements.

Lex&Forum is renewing its appointment with its readers in the upcoming issue, dedicated to the latest updates concerning the Hague Convention for the unification of private international law, especially after the EU’s succession.