The Dubai Supreme Court on Indirect Jurisdiction – A Ray of Clarity after a Long Fog of Uncertainty?

I. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments depend, first and foremost, on whether the foreign court issuing the judgment was competent to hear the dispute (see Béligh Elbalti, “The Jurisdiction of Foreign Courts and the Enforcement of Their Judgments in Tunisia: A Need for Reconsideration”, 8 Journal of Private International Law 2 (2012) 199). This is often referred to as “indirect jurisdiction,” a term generally attributed to the renowned French scholar Bartin. (For more on the life and work of this influential figure, see Samuel Fulli-Lemaire, “Bartin, Etienne”, in J. Basedow et al. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Private International Law – Vol. I (2017) 151.)

Broadly speaking, indirect jurisdiction refers to the jurisdiction of the foreign court in the context of recognizing and enforcing foreign judgments. Concretely, the court being asked to recognize and enforce a foreign judgment evaluates whether the foreign court had proper jurisdiction to hear the dispute. The term “indirect” distinguishes this concept from its legal opposite: direct jurisdiction. Unlike indirect jurisdiction, direct jurisdiction refers to the authority (international jurisdiction) of a domestic court to hear and adjudicate a dispute involving a foreign element (see Ralf Michaels, “Some Fundamental Jurisdictional Conceptions as Applied in Judgment Conventions,” in E. Gottschalk et al. (eds.), Conflict of Laws in a Globalized World (2007) 35).

While indirect jurisdiction is universally admitted in national legislation and international conventions on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments, the standard based on which this requirement is examined vary at best running the gamut from a quite loose standard (usually limited only to the examination of whether the dispute fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the requested court as legally determined in a limitative manner), to a very restrictive one (excluding the indirect jurisdiction of the rendering court every time the jurisdiction of the requested court – usually determined in a very broad manner – is verified). The UAE traditionally belonged to this latter group (for a comparative overview in MENA Arab Jurisdictions, see Béligh Elbalti, “Perspective of Arab Countries,” in M. Weller et al. (eds.), The 2019 HCCH Judgments Convention – Cornerstones, Prospects, Outlook (2023) 187-188; Idem “The Recognition of Foreign Judgments as a Tool of Economic Integration – Views from Middle Eastern and Arab Gulf Countries, in P Sooksripaisarnkit and S R Garimella, China’s One Belt One Road Initiative and Private International Law (2018) 226-229). Indeed, despite the legal reform introduced in 2018 (see infra), UAE courts have continued to adhere to their stringent approach to indirect jurisdiction. However, as the case reported here shows this might no longer be the case. The recent Dubai Supreme Court’s decision in the Appeal No. 339/2023 of 15 August 2024 confirms a latent trend observed in the UAE, particularly in Dubai, thus introducing a significant shift towards the liberalization of the recognition and enforcement requirements. Although some questions remain as to the reach of this case and its consequences, it remains a very important decision and therefore warrants attention.

II. Facts

The summaries of facts in UAE courts’ decisions are sometimes sparse in details. This one particularly lacks the information necessary to fully understand the case.

What can be inferred from the description of facts in the decision is that the dispute involved two Polish parties, a company as a plaintiff (hereafter referred to as “X”) and a seemingly a natural person as a defendant (hereafter referred to as “Y”) who has his “residence [iqamah]” in Dubai.

X was successful in the action it brought against Y in Poland and obtained a judgment ordering the latter to pay a certain amount of money. Later, X sought to enforce the Polish judgment in Dubai.

X’s enforcement petition was first admitted by the Execution Court of Dubai. On appeal, the Dubai Court of Appeal overturned the enforcement order on the ground that the international jurisdiction over the dispute lied with Dubai courts since Y had his “residence” in Dubai. Dissatisfied, X filed an appeal before the Dubai Supreme Court.

Before the Supreme Court, X argued that Y’s residence in the UAE does not prevent actions from being brought against him in his home country, where the “event [waqi’a]” giving rise to the dispute occurred, particularly since both parties hold the same nationality. In addition, X claimed that it was not aware that Y’s residence was in the UAE.

III. The Ruling

The Supreme Court admitted the appeal and overturned the appealed decision with remand.

In its ruling, and after recalling the basic rules on statutory interpretation, the Supreme Court held as follows:

“According to Article 85 paragraph [……] of the Executive Regulation of the Civil Procedure Act (issued by Cabinet Decision No. 57/2018,[i] applicable to the case in question), [……], “enforcement shall not be ordered unless the following is verified: “UAE courts do not have exclusive jurisdiction over the dispute [……], and that the foreign rendering court had jurisdiction according to its own laws.”

“This clearly indicates that the legislator did not allow enforcement orders to be granted [……] unless UAE courts do not have exclusive jurisdiction over the dispute in which the foreign judgment to be declared enforceable was rendered. Therefore, in case of concurrent jurisdiction between UAE courts and the foreign rendering court, and both courts are competent to hear the dispute, this does not, by itself, prevent the granting of the enforcement order. This marks a departure from the previous approach prior to the aforementioned Executive Regulation, where, under the provisions of Article 235 of Federal Act on Civil Procedure No. 11/1992,[ii] it was sufficient to refuse the enforcement of a foreign judgment if the UAE courts were found to have jurisdiction over the dispute—even if their jurisdiction was not exclusive. [This continued to be the case until] the legislator intervened to address the issue of the jurisdiction that is exclusive to UAE courts [as the requested State] and concurrent jurisdiction that shared the foreign rendering court whose judgment is sought to be enforced [in UAE]. [Indeed,] the abovementioned 2018 Executive Regulation resolved this issue by clarifying that what prevents from declaring a foreign judgment enforceable is [the fact that] UAE courts are conferred exclusive jurisdiction over the dispute in which the foreign judgment was rendered. This was reaffirmed in [……] in [the new] Article 222 of the Civil Procedure Law issued by Federal Decree-Law No. 42 of 2022,[iii] which maintained this requirement [without modification].

[…] the appealed decision departed from this point view, and overturned the order declaring the foreign judgment in question enforceable on the ground that Y resides UAE, which grants jurisdiction to Dubai courts over the dispute […], despite the fact that [this] basis [of jurisdiction] referred to by the appealed decision [i.e. – the defendant’s residence in the UAE] does not grant exclusive jurisdiction to UAE courts to the exclusion of the foreign rendering court’s jurisdiction. Therefore, the ruling misapplied the law and should be overturned.” (underline added)

IV. Analyses

The conclusion of the Dubai Supreme Court must be approved. The decision provides indeed a welcome, and a much-awaited clarification regarding what can be considered one of the most controversial requirements in the UAE enforcement system. In a previous post, I mentioned indirect jurisdiction as one of the common grounds based on which UAE courts have often refused to recognize an enforce foreign judgments in addition to reciprocity and public policy.[iv] This is because, as explained elsewhere (Elbalti, op. cit), the UAE has probably one of the most stringent standard to review a foreign court’s indirect jurisdiction.

1. Indirect jurisdiction – Standard of control

The standard for recognizing foreign judgments under UAE law involves three layers of control (former article 235 of the 1992 FACP). First, UAE courts must not have jurisdiction over the case in which the foreign judgment was issued(former article 235(2)(a) first half of the 1992 FACP). Second, the foreign court must have exercised jurisdiction in accordance with its rules of international jurisdiction (former article 235(2)(a) second half of the 1992 FACP). Third, the foreign court’s jurisdiction must align with its domestic law, which includes both subject-matter and territorial jurisdiction, as interpreted by the court (former Article 235(2)(b) of the 1992 FACP).

a) Traditional (stringent) position under the then applicable provisions

The interpretation and application of the first rule have been particularly problematic as UAE courts. The courts have, indeed, often rejected foreign courts’ indirect jurisdiction when UAE jurisdiction can be justified under the expansive UAE rules of direct jurisdiction (former articles 20 to 23 of the 1992 FACP), even when the foreign court is validly competent by its own standards (Dubai Supreme Court, Appeal No. 114/1993 of 26 September 1993 [Hong Kong judgment in a contractual dispute – defendant’s domicile in Dubai]). Further complicating the issue, UAE courts tend to view their jurisdiction as mandatory and routinely nullify agreements that attempt to derogate from it (article 24 of the 1992 FACP, current article 23 of the 2022 FACP. See e.g., Federal Supreme Court, Appeals No. 311 & 325/14 of 20 March 1994; Dubai Supreme Court, Appeals No. 244 & 265/2010 of 9 November 2010; Abu Dhabi Supreme Court, Appeal No. 733/2019 of 20 August 2019).

b) Case law application

While there are rare cases where UAE courts have accepted the indirect jurisdiction of a foreign court, either based on the law of the rendering state (see e.g., Abu Dhabi Supreme Court, Appeal No. 1366/2009 of 13 January 2010) or by determining that their own jurisdiction does not exclude foreign jurisdiction unless the dispute falls under their exclusive authority (see e.g., Abu Dhabi Supreme Court, Appeal No. 36/2007 of 28 November 2007), the majority of cases have adhered to the traditional restrictive view (see e.g., Federal Supreme Court, Appeal No. 60/25 of 11 December 2004; Dubai Supreme Court, Appeal No. 240/2017 of 27 July 2017 ; Abu Dhabi Supreme Court, Appeal No. 106/2016 of 11 May 2016). This holds true even when the foreign court’s jurisdiction is based on a choice of court agreement (see e.g., Dubai Supreme Court, Appeal No. 52/2019 of 18 April 2019). Notably, UAE courts have sometimes favored local interpretations over international conventions governing indirect jurisdiction, even when such conventions were applicable (see e.g., Dubai Supreme Court, Appeal No. 468/2017 of 14 December 2017; Abu Dhabi Supreme Court, Appeal No. 238/2017 of 11 October 2017. But contra, see e.g., Dubai Supreme Court, Appeal No. 87/2009 of 22 December 2009; Federal Supreme Court, Appeal 5/2004 of 26 June 2006).

2. The 2018 Reform and its confirmation in 2022

The 2018 reform of the FACP introduced significant changes to the enforcement of foreign judgments, now outlined in the 2018 Executive Regulation (articles 85–88) and later confirmed in the new 2022 FACP (articles 222~225). One of the key modifications was the clarification that UAE courts’ exclusive jurisdiction should only be a factor when the dispute falls under their exclusive authority (Art. 85(2)(a) of the 2018 Executive Regulation; article 222(2)(a) of the new 2022 FACP). While courts initially continued adhering to older interpretations, a shift toward the new rule emerged, as evidenced by a case involving the enforcement of a Singaporean judgment (which I previously reported here in the comments). In this case, Dubai courts upheld the foreign judgment, acknowledging that their jurisdiction, though applicable, was not exclusive (Dubai Court of First Instance, Case No. 968/2020 of 7 April 2021). The Dubai Supreme Court further confirmed this approach by dismissing an appeal that sought to challenge the judgment’s enforcement (Appeal No. 415/2021 of 30 December 2021). This case is among the first to reflect a new, more expansive interpretation of UAE courts’ recognition of foreign judgments, aligning with the intent behind the 2018 reform.

3. Legal implications of the new decision and the way forward

The Dubai Supreme Court’s decision in the case reported here signifies a clear shift in the UAE’s policy toward recognizing and enforcing foreign judgments. This ruling addresses a critical issue within the UAE’s enforcement regime and aligns with broader trends in global legal systems (see Béligh Elbalti, “Spontaneous Harmonization and the Liberalization of the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments” 16 Japanese Yearbook of Private International Law (2014) 273). As such, the significance of this development cannot be underestimated.

However, there is a notable caveat: while the ruling establishes that enforcement will be granted if UAE courts do not have exclusive jurisdiction, the question remains as to which cases fall under the UAE courts’ exclusive jurisdiction. The 2022 FACP does not provide clarity on this matter. One possible exception can be inferred from the 2022 FACP’s regulation of direct jurisdiction which confers broad jurisdiction to UAE courts, “except for actions relating to immovable located abroad” (article 19 of the 2022 FACP). Another exception is provided for in Article 5(2) of the Federal Act on Commercial Agencies,[v] which subjects all disputes regarding commercial agencies in UAE to the jurisdiction of the UAE courts (see e.g., Federal Supreme Appeal No. 318/18 of 12 November 1996).

Finally, one can question the relevance of the three-layer control of the indirect jurisdiction of foreign courts, particularly regarding the assessment of whether the foreign court had jurisdiction based on its own rules of both domestic and international jurisdiction. It seems rather peculiar that a UAE judge would be considered more knowledgeable or better equipped to determine that these rules were misapplied by a foreign judge, who is presumably well-versed in the legal framework of their own jurisdiction. This raises concerns about the efficiency and fairness of such a control mechanism, as it could lead to inconsistent or overly stringent standards in evaluating foreign judgments. These requirements are thus called to be abolished.

———————————————

[i] The 2018 Executive Regulation Implementing the 1992 Federal Act on Civil Procedure (Cabinet decision No. 57/2018 of 9 December 2018, as subsequently amended notably by the Cabinet Decision No.75/2021 of 30 August 2021; hereafter referred to as “2018 Executive Regulation”.)

[ii] The 1992 Federal Act on Civil Procedure (Federal Law No. 11/1992 of 24 February 1992, hereafter “1992 FACP”).

[iii] The 2022 Federal Act on Civil Procedure (Federal Legislative Decree No. 42/2022 of 30 October 2022). The Act abolished and replaced the 2018 Executive Regulation and the 1992 FACP (hereafter “2022 FACP”).

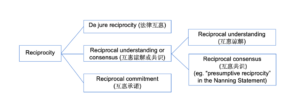

[iv] However, since then, there have been subsequent developments regarding reciprocity that warrant attention as reported here.

[v] Federal Law No. 3/2022 of 13 December 2022 regulating Commercial Agencies, which repealed and replaced the former Federal Law No. 18/1982 of 11 August 1981.