The general course in private international law delivered at the Hague Academy of International Law by Louis d’Avout during the 2022 Summer Session was published in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series (1 032 pages). Louis d’Avout is Professor at Université Paris Panthéon-Assas. In addition to his numerous scholarly works, readers of this blog may recall that his special course on “L’entreprise et les conflits internationaux de lois” was also published in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series in 2019. The general course is title « La cohérence mondiale du droit » (“The Global Coherence of Law”). The publication of a general course in private international law—particularly in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series—deserves the attention of the readers of this blog. The aim of this review is, modestly, to offer a glimpse into this important work so readers who are sufficiently francophone may be encouraged to read it directly, while those who are not are offered a brief overview of the author’s approach.

The general course in private international law delivered at the Hague Academy of International Law by Louis d’Avout during the 2022 Summer Session was published in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series (1 032 pages). Louis d’Avout is Professor at Université Paris Panthéon-Assas. In addition to his numerous scholarly works, readers of this blog may recall that his special course on “L’entreprise et les conflits internationaux de lois” was also published in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series in 2019. The general course is title « La cohérence mondiale du droit » (“The Global Coherence of Law”). The publication of a general course in private international law—particularly in the Academy’s Pocket Books Series—deserves the attention of the readers of this blog. The aim of this review is, modestly, to offer a glimpse into this important work so readers who are sufficiently francophone may be encouraged to read it directly, while those who are not are offered a brief overview of the author’s approach.

Two caveats. First, translations, and inevitable related inaccuracies, are mine. Second, it should be stated at the outset that a work of such scope is not easily summarized: the demonstration, subtle and original, is based on detailed and nuanced analyses and is supported by an impressive bibliographical apparatus, of remarkable diversity. One may note in that respect the author’s relentless effort to draw on a very large number of courses delivered at the Academy of International Law, both in private and in public international law. It is unfortunately impossible to reflect such wealth in the present review other than in a very selective manner.

The course’s program

The program of the course as encapsulated in the title is ambitious. The idea of “coherence” in law, and especially in private international law (PIL), is particularly evocative. On the one hand, it evokes the often recalled need to preserve the coherence of the forum’s legal order in the face of the disturbance that foreign norms may generate. On the other hand, it also conveys the traditional objective pursued by conflict of laws: the international harmony of solutions. The use of the term “global” (mondiale) gives this search for coherence a particular breadth: it does not concern merely the legal treatment of international or transnational private relationships—the traditional object of private international law—but rather the articulation of legal regimes (State and non-State, domestic and international, public and private) whose still largely disordered coexistence is one of the defining features of our time. As will be seen, the perspective adopted in the course is normative, oriented toward the pursuit of global legal coherence. This search must be understood in a double sense: to uncover coherence where it exists, and to restore it where it does not. At a first level, coherence refers to the rationality and predictability of legal regimes, as well as to their effectiveness. Such coherence (or at least the aspiration to it) is regarded by the author as consubstantial with law itself.

The context in which this search for coherence unfolds is marked by a triple dynamic. On the one hand, increased individual mobility and technological change have diminished the relevance of geographical distance, and even of the crossing of borders. On the other hand, and correlatively, new forms of inter-State cooperation or coordination have emerged. Added to this is the development of non-State and/or transnational legal regimes. These factors give rise to collisions between legal regimes, confronting individuals and enterprises alike. The author proposes to draw on the technical and conceptual wealth of private international law in order to bring coherence to this normative disorder. After all, PIL has a (multi-)millennial experience in resolving conflicts of norms.

Two points are central to the author’s approach. First, the search for coherence must be conducted at the supra-State level. The State level is still relevant for reasoning about conflicts of norms and their resolution, but with a view to a “framework extended to global society” (p. 29). Second, although the search for coherence benefits individuals, it does not necessarily entail a subjective right of individuals to the transnational coherence of law, that is, a right to enjoy a single legal status notwithstanding the crossing of borders and the diversity of legal systems (p. 41).

Starting point and definitions

After a brief historical overview presented in six evocative tableaux, the author examines the merits of three intellectual representations of the discipline, all of which share a connection with general international law: State-centrism, inter-Statism, and the allocation of jurisdiction. The author’s approach is structured by this concern with the relationship between private and public international law. In so doing, he deliberately continues a doctrinal current that has become rather minority in contemporary PIL scholarship (at least in France). In any event, private international law brings together mechanisms for opening State legal orders and articulating them with one another (p. 111).

The author then turns to defining “inter-State and transnational coherence of law” (p. 112). He devotes particularly dense pages to this issue, pages which are difficult to summarize but are decisive for the originality of his perspective. He emphasizes institutional and procedural coherence—that is, the institutions, procedures, mechanisms and actors whose work produces coherence. This procedural coherence is fundamental and constitutes a sine qua non condition of a legal system, whereas normative coherence (the consistency and logical character of the solutions produced) is both secondary—since it flows from institutional and procedural work—and closer to an ideal, often imperfectly achieved.

Equally decisive is the author’s conviction as to the necessity of coherence. The “praise of incoherence” (p. 127) is dismissed as stemming from a confusion between normative coherence and institutional coherence: the former, being ideal, may fail to convince, whereas the latter is genuinely necessary for the jurist. In short, coherence and incoherence are opposing poles of a complex reality; the existence of incoherences is not sufficient to discredit the need for coherence. As a result, coherence is both necessary and achievable.

Basically, incoherence arises from the tendency of legal systems—particularly the most sophisticated and robust among them, namely States—to reason in autarchy and to impose their own viewpoint (often in the name of their internal coherence) at the expense of the “global rationality of the law applied”. What makes coherence possible is the openness of legal systems to one another (and thus openness to otherness) and their willingness to cooperate. The international (public) legal order itself is marked by a corresponding tension between unilateralism (each sovereign acting alone) and concertation (sovereigns acting together). Coherence in the international order may follow a horizontal (inter-State) or a vertical (supra-State) model. The vertical, supra-State and overarching (tending toward monism) model allows for a form of universality (a jus commune). By contrast, the horizontal model is characterized by pluralism. The author associates each model with a method of private international law: verticality and monism allow for bilateralism, whereas horizontality (and pluralism) implies unilateralism (p. 169).

The book’s outline and summary

The horizontal/vertical distinction structures the book. The first part is devoted to the study of horizontal interactions: independent “legal spheres” interact with one another, coherence is not guaranteed but may be produced through mutual consideration and interaction. The second part focuses on institutional verticalization, a partial and complementary dynamic (limited to certain sectors or regions of the world), based on the creation and intervention of supra-State bodies capable of producing coherence for the benefit of individuals.

Horizontal interactions between legal systems

The first part of the course is therefore devoted to what the author terms “horizontal” interactions between “independent legal spheres”. In this context, he examines the mechanisms of classical private international law: conflicts of laws and conflicts of jurisdictions or authorities. Here, the “conjunction” of viewpoints (that is, of legal orders) with respect to an international private relationship is, in a sense, voluntary rather than mandatory. It operates through two main sets of mechanisms: first, the attachment of situations to a particular law, court, or authority; and second, cross-border cooperation between authorities (for example, the taking of evidence, the delegation of formalities, or the enforcement of judgments).

The spirit of Relativism

In the first chapter, the author sets out the rudimentary elements of the discipline. These rudiments appear clearly in historical perspective. He explores the tools spontaneously used by courts in order to take account of the foreignness of a person or a situation vis-à-vis the forum. This perspective is original, in particular because it does not merely recount a historical evolution but demonstrates the persistence of these instruments in contemporary PIL. The earliest manifestations of the openness of State legal orders were guided by a concern to achieve equity “formulated from the standpoint of the lex fori”, through recognition of the foreign elements of the situation to be regulated, combined with interpretative techniques applied to the law of the forum to reach a fair outcome. The author emphasizes that these instruments, rudimentary though they may be, are not devoid of subtlety. At their root lies a form of judicial spontaneity oriented toward the pursuit of equity in cross-border relationships.

This pursuit is guided by a spirit of legal relativity: the transnational private relationship is exposed to a diversity “of laws, customs or values” (p. 187), and this diversity must be considered. The author thus shows how foreignness and relativity constitute the foundational elements of what he terms “international civil law”. The foreigner receives particular treatment when the lex fori is applied, and the international or foreign situation calls either for a reception mechanism (and, correlatively, for limits to relativism, notably an international public policy exception subject to modulation), or for a form of spatial limitation of the lex fori (as exemplified by the presumption against extraterritoriality in U.S. law). The author further demonstrates how these instruments continue to be used in contemporary law to manage situations of legal otherness within the domestic legal order itself. States are prompted to limit the undifferentiated and uniform application of their own laws through compromise solutions, often entrusted to the judiciary (see, from this perspective, the discussion of the Molla Sali judgment of the European Court of Human Rights, p. 218). The identity of individuals may likewise warrant specific accommodations from the inward pull of communities. The author reflects on the relationship between this spirit of relativism (both international and internal) and a form of liberal individualism, particularly as expressed through the growing judicial consideration of fundamental rights. From this perspective, the application of the principle of proportionality in private law may be seen as a manifestation of this spirit of relativity.

The author then explores the tactics developed by judges—and still employed today—to loosen, where necessary, the constraints of the lex fori, which remains the unavoidable starting point for the forum judge when confronted with an international situation. These tactics include the self-limitation of the law of the forum (see, for example, the analysis of the Gonzalez-Gomez decision of the French Conseil d’État, p. 266), creative interpretation of the lex fori, prise en consideration of foreign law, and judge-made international substantive rules. Judicial creativity, however, has its limits: true conflicts are difficult to overcome (see the analysis of unilateral techniques, p. 290 et seq.). The spontaneous modulation of the lex fori, while significant, reveals certain weaknesses and highlights the need for a selective method that appears to “allocate competences among the various legal spheres or among the different poles of law production” (p. 217).

Connecting factors and conflicts rules

The following chapter is devoted to connecting factors, whether from the standpoint of jurisdictional competence or of the applicability of laws. One of the drawbacks of the spontaneous judicial method of adapting the lex fori described in the preceding chapter lies in its casuistic nature, which proves ill-suited to the massification of international private relationships. The author defines the technique of connecting factors in general terms as establishing a rational link between a transnational situation and either a specific legal regime, whether domestic or conventional, or a collective entity (a State or an international organization) (p. 319). He devotes particularly thorough and insightful developments to connecting factors, highlighting their richness, diversity and complexity (see the synthesis at p. 344 et seq.).

Among other points, the author rejects an overly rigid opposition between unilateralism and bilateralism, noting that “the connecting operation may function in both directions” (p. 323): the connecting factor may operate either on the side of the legal consequence or on that of the presupposition of the rule. He usefully distinguishes between the policy of the connecting factor—that is, the intention guiding its author—and the justice of the connecting factor, which results from it and may be assessed independently. The respective connecting roles of bilateral conflict-of-laws rules, unilateral applicability rules, and jurisdictional rules are thus clarified. In another original move, the author also draws a link between the recognition of a foreign judgment and the operation of connecting factors, particularly from the perspective of reviewing the origin of the judgment (indirect jurisdiction).

Following these general observations, the author successively examines jurisdictional connecting factors (judicial or administrative) and substantive connecting factors. With regard to the former, one may summarize (see p. 398) the rich analyses developed as follows. Jurisdictional (or administrative) connecting factors are distinct from substantive connecting factors. They are unilateral (save under conventional regimes) and generally plural and alternative (with some exceptions), giving rise to a situation of “concurrent international availability” of authorities belonging to several legal orders. These connecting factors are not purely localizing: they always have a purpose grounded in considerations of appropriateness, sometimes linked to substantive aspects of the dispute. In any event, the connecting factor is not purely procedural. It affects the substance of the dispute (the forum applies its own procedural law and its own private international law), and it expresses a (legal) policy, understood as a balancing of the interests at stake. As regards administrative authorities, the connecting factors adopted are generally dictated by the applicability of the administrative law concerned, which the authority is tasked with enforcing (according to the model of the lex auctoris). The unilateral and diverse nature of jurisdictional rules creates risks for the coherence of the legal treatment of situations, thus calling for conciliatory mechanisms, namely the forum’s consideration of foreign judicial activity.

With respect to “substantive connecting factors” (conflict of laws rules, then), L. d’Avout claims from the outset a “substantive impregnation of the rules, imbued with objectives and revealing legal policies forged by their authors” (p. 402). These considerations are sometimes specific to the international context and sometimes derive from the orientations of domestic substantive law (often a combination of both). Faithful to his commitment to methodological flexibility, the author develops the idea of a progressive crystallization of synthetic bilateral rules, starting from an intuitive unilateralism (see pp. 412–416). Here he draws on the German doctrine of Bündelung (with reference to Schurig). This approach is convincing with regard to the formation of connecting categories. It is complemented by a sophisticated functional approach (with reference to the work of Professor Brilmayer in the United States). The choice of a connecting factor is above all a matter of appropriateness, taking into account both the divergent interests of the individuals directly concerned and, through consideration of externalities, the collective interests affected by the situation (p. 435).

These balances are struck by the author of the rule and are therefore liable to vary from one State to another, or where the rule has been adopted at a supranational level (for example, at the European level). The author thus distances himself from an apolitical, universalist, but also singularist vision of the discipline: the conflict-of-laws rule is a rule like any other, a deliberate rule. On this basis, the author addresses the classical difficulties of the conflict-of-laws method: characterization and dépeçage (pp. 439 et seq.), conflicts of systems (p. 443), and the authority of the conflict-of-laws rule (p. 447). In each case, the analyses are guided by the previously articulated teleological precepts, without any particular search for originality for its own sake (as the author himself acknowledges), but rather by a concern for… coherence.

The pragmatism advocated by the author is not exclusive of visceral attachment to the conflict-of-laws rule as a rule. Targeted adjustments that depart from this abstract mode of regulation (such as the escape clause or the recognition method) have their place, but they must remain subsidiary and be used with caution. Concluding on this point, the author offers a nuanced diagnosis of the connecting rule. As an international extension of domestic legislation, it is indeed an instrument of coherence (or at least of cohesion). Being anchored in the legal order that adopts it, it is however not capable—at least not systematically—of ensuring “the harmonious junction of legal spheres” (p. 473). Mechanical application must therefore be avoided, and the rule must be accompanied by a cooperative attitude, thus offering a transition to the following chapter.

Transnational cooperation

The final chapter of the first part is accordingly devoted to “transnational cooperation” and “communications between authorities”. The author adopts a broad conception of transnational judicial cooperation, ranging from ancillary technical cooperation (such as the taking of evidence or service of documents) to what he terms cooperation-communication, and even co-determination of solutions (p. 477). These mechanisms are important because they offer some remedy to the shortcomings identified earlier (competing jurisdictions and divergence in substantive connecting rules).

The prominence given to these instruments and the analyses developed in this chapter constitute arguably one of the course’s most strikingly original contributions. To be sure, significant scholarly work has already been devoted to international judicial cooperation (see the references cited in the chapter’s introduction). The analyses presented here stand out nonetheless both for their ambition to offer a comprehensive reflection on mechanisms that had previously often been addressed piecemeal, and, above all, for their full integration into a private international law framework, on an equal footing, so to speak, with the conflict-of-laws rule. This innovation is made possible by the course’s overarching perspective, since transnational judicial cooperation is fully part of the search for the global coherence of law.

L. d’Avout proposes a useful typology: administrative or judicial assistance or mutual legal assistance (acts auxiliary to the main proceedings); cooperation at the periphery of the main proceedings (a category that includes the recognition of judgments and public acts—see the justification at p. 499 et seq.); and more innovative hypotheses of co-determination of legal solutions, whether within a conventional framework (the example given is the 1993 Hague Convention on the Protection of Children, p. 507) or through spontaneous coordination. It is in respect of this last category that the developments are the most interesting and innovative (see the examples given at p. 519 et seq.).

On this basis, the author constructs a genuine theory of the concerted resolution of international disputes (illustrated by a traffic-light metaphor, p. 530). Without being able to go into the details of this theory here, its starting point lies in the ideal unity of the proceedings on the merits, possibly supplemented abroad by collaborative ancillary measures and by a subsequent review of acceptability (namely, recognition of the judgment on the merits). Because this ideal is not always achievable—nor even always desirable—additional instruments exist to ensure reciprocal consideration of judicial activity: stays of proceedings (potentially conditional upon a prognosis as to the regularity of the forthcoming judgment), or even the forum’s consideration of the likely outcome of the foreign proceedings. Instruments for managing procedural conflicts also occupy a prominent place (p. 536 et seq.).

The search for coherence does not, however, imply an idealized view of international litigation: frictions do exist, and they cannot always be avoided. What matters is to identify their causes and consequences clearly, rather than proceeding in isolation and disregarding their effects (whether for the parties, or one of them, or for the objectives pursued within a given branch of law). After examining several areas particularly conducive to transnational judicial concertation (family litigation, insolvency, and collective proceedings), the author proposes both existing and potential tools, advancing several stimulating proposals: the transnational procedural agreement and the transnational preliminary reference (question préjudicielle transnationale), to name a few. Should one then recognize an autonomous duty of cooperation incumbent upon judges or authorities in international cases? Characteristically, the author’s answer is cautious: cooperation is not the primary mission of the judge or of an administrative authority; it remains secondary (p. 575).

Having thus explored the avenues of horizontal cooperation between legal systems—demonstrating both their potential and their limits—and following a rich intermediate conclusion, the author turns to the phenomenon of partial verticalization, which represents their transcendence.

Verticalization

The second part, entitled “Verticalization – Institutional Responses to the Interpenetration of Legal Spheres”, may come as something of a surprise to readers. Indeed, as it goes beyond the horizontality examined thus far, it tends to move away from the classical perspective of private international law. For the author, however, this movement is a natural one, as only a supranational construction is capable of overcoming the residual oppositions between States’ viewpoints. The approach unfolds in two successive stages. The first form of verticality examined is that of federative organizations, such as the European Union, whose role in coordinating legal regimes is undeniable. The second (and more exploratory) form of verticality concerns international law itself: are there international institutions that can be leveraged in the service of the global coherence of law?

The role of federative organizations

The first chapter of this second part examines “the coherence of law through federative organizations”, that is to say, new modes of articulating legal regimes and of reducing the accumulation and conflict of international rules. The demonstration begins with European regimes of coordination in public law insofar as they affect individuals and companies. European measures facilitating administrative procedures have made it possible to remedy the overlap of national legislation or administrative procedures that necessarily results from individual mobility. European integration has also established articulations of State competences to the same end. Likewise, European Union law has fostered the polymorphous mobility of companies by organizing the normative and administrative interventions of the Member States. The chapter offers further, equally convincing examples: federative organizations effectively articulate sovereignties. The author further proposes a distinction between two aspects : the intensification of horizontal cooperation and institutional federalism.

The first aspect provides an opportunity to examine mutual recognition as a form of articulation of competences, as well as its limits (p. 664 et seq.). While acknowledging the major achievements of European integration, the author rightly insists on the need to avoid imposing automatic recognition where the underlying control whose outcome is being recognized has not been fully harmonized. The second aspect developed concerns the action of supranational administrative bodies.

The author then turns to the “vertical discipline of conflicts of laws in the interest of private persons”. The issue here is to assess the impact of federative organization on the configuration and resolution of conflicts of laws. Following a preliminary discussion addressing the matter from an institutional perspective (in the form of an illuminating EU–US comparison), the author devotes profound developments to the renewal of conflict-of-laws reasoning brought about by institutional verticality. At the heart of this reflection lies the figure of the supranational judge, an external third party to conflicts of laws between Member States, and a point of “triangulation” of these opposing viewpoints.

Without being able to reproduce the entirety of the argument here, it may be noted that it leads the author to issue the following warning: “an analysis of current law does not support the emergence, within regional spaces, of an unconditional right of individuals to the transnational coherence of law and to a resolution of conflicts of laws favorable to them” (p. 725). Supranational courts that were to lose sight of this would expose themselves to the risk of “judge-made legislation”. The author nevertheless identifies “an intensified duty to take account of discordant viewpoints and, at times, to articulate them in novel ways, in application of the organization’s law and in the absence of harmonization by it of the applicable law”. Particular attention should be drawn to the author’s precise reassessment of the figure of so-called “diagonal conflicts”, based on a fruitful distinction between horizontal conflicts resolved along the vertical axis through fundamental rights, and frictions between a supranational regime and a State regime (see pp. 761 et seq.).

Verticality in public international law

The final chapter is both the natural culmination of the overall demonstration and one that will likely most surprise PIL scholars. Having examined the effects of the verticality of federative organizations of States on conflicts between legal regimes, the author considers it natural to search directly within international law for instruments capable of coordinating legal regimes applicable to private persons. The surprise may stem from the fact that contemporary private international law doctrine—at least in France—has largely ceased to look to general international law as a remedy for deficits in legal coordination.

The author’s perspective here is once again innovative. While there is no substantive subjective right of individuals or companies exposed to discordant legal treatment, the possibility of a procedural subjective right may be envisaged “insofar as such a faculty allows, either immediately or following unsuccessful recourse before State bodies, access to an impartial judge capable of stating the law or of reviewing the manner in which it has previously been applied” (p. 795). The author thus embarks on a quest for this emerging procedural right in its various modalities (individual claims against the State; claims mediated through another State or an international organization). This leads him to explore avenues as diverse as investment arbitration, the fascinating experience of binational courts (and their spontaneous production of private international law solutions, p. 819 et seq.), as well as the International Court of Justice, whose case law is scrutinized to detect the tentative emergence of substantive rights of individuals. The author perceives here a potential for a de-specialization of the Law of Nations through the expansion of its addressees (p. 874).

The author then turns to international institutional fragmentation, that is, the fragmentation of the various regimes (territorial State regimes, special international regimes). He concludes that techniques of horizontal interaction between these legal spheres should be developed, and possibly even hierarchical principles (p. 901). A solution might lie in seizing an authority capable of arbitrating conflicts of competences exercised by independent international bodies, by expanding the advisory procedure before the International Court of Justice, or even by entrusting it with a mission of resolving these conflicts of competence.

Finally, the author seeks to determine whether, in order to transcend the multiplicity of clashing legal regimes, it might be possible to invent and construct a new “jus commune” (droit commun). He advances three series of proposals or concluding observations in this regard. The first concerns the contemporary role of States and State sovereignty: the author calls for the consolidation of an “interface State between local communities and distant communities” (p. 920). In his view, “the durable persistence of State organization requires a minimum level of inter-State cooperation”. The second series of observations concern the possibility of the emergence of this universal jus commune and its defining qualities. The author focuses on points of convergence (principles, values, standards) that make it possible to discern a phenomenon of conjunction between norms of diverse origins. Finally, the author returns once more to the legal discordances affecting international relations to emphasize that, beyond disciplinary, conceptual, and terminological distinctions, a single problem emerges: the lack of coordination between autonomous legal spheres. Given contemporary developments in human societies, spatial mechanisms for resolving certain of these discordances may appear less relevant. What is therefore required is a genuinely substantive coordination, resting on the production of concerted solutions (in the various forms discussed above). For the most difficult cases, the subsidiary intervention of a supranational court could be envisaged.

Highlights

Within the limited space of this review, it is unfortunately not possible to engage in a detailed discussion of the analyses developed, other than by pointing to them in the summary above and advancing the following few remarks, necessarily too general.

The summary above perhaps gives a sense of the scope of the demonstration undertaken. It is particularly impressive and compelling in that it escapes the traditional boundaries of the discipline to embrace the globality of the phenomenon of normative fragmentation. Such an undertaking is remarkable. Global legal incoherences are numerous and addressing them solely through the lens of conflicts of laws or conflicts of jurisdiction would inevitably have been reductive. Moreover, as befits the ambition of a general course, the book offers a comprehensive and original framework for understanding the discipline. It is in a sense conceptualized anew (in object and methods) and endowed with a new vocabulary. This reconceptualization does not however entail revolutionary breaks with existing solutions. Nor is that its ambition: the author warns repeatedly against such ventures. Rather it provides a new perspective that enables regenerating analyses. The author never yields to the temptation of a purely hierarchical response to legal discordances, nor does he idealize horizontality as a sufficient answer to the conflicts generated by the interpenetration of legal spheres. Instead, he patiently reconstructs the diversity of techniques available—horizontal, vertical, institutional, procedural—and evaluates their respective capacities to achieve coherence without sacrificing pluralism. Also worthy of note is the deliberate choice to avoid doctrinal factionalism (unilateralism vs. bilateralism; localizing vs. substantive approaches; monism vs. pluralism) by adopting a generally pragmatic stance. The demonstration is constantly guided by a concern for individuals and economic actors confronted with the accumulation of fragmented regimes. Without positing the existence of a general subjective right to legal coherence, the author identifies concrete expectations, procedural guarantees, and institutional mechanisms capable of mitigating the most difficult effects of normative fragmentation.

The author concludes with a quote from Savigny, inviting contemporaries to make full use of the doctrinal heritage accumulated in order to contribute to the advancement of scientific progress in the field. This quotation is doubly revealing of the author’s approach. First, the call to exploit accumulated doctrinal wealth is followed here with impressive determination. On every page, the author is keen to draw from both older and more recent sources, and to give resonance to the diversity of viewpoints. Second, the demonstration appears to be guided by an idea of progress: not in the sense that contemporary doctrine or case law would be superior to that of the past, but, as Savigny suggests, in the sense that the conflict-of-laws discipline itself progresses—and thus the coherence of law progresses—through “the combined forces of past centuries.” Without lapsing into naïveté, the argument reflects a form of optimism on the part of the author regarding the march toward global legal coherence. Such optimism is commendable. It may nevertheless be argued that belief in coherence as a cardinal value is not today universal, within and without the law. Thus, for example, the idea that irrational (incoherent) behavior by a State exposes it to sanctions (from within!, p. 920) unfortunately suffers daily contradiction. Moreover, multilateralism is undergoing a crisis so profound (for instance explored here by P. Franzina, from a private international law perspective) that some argue, not without reason, that it has never existed other than as a façade (as contended by the Prime Minister of Canada in a recent speech in Davos). Just over three years after this course was delivered at The Hague Academy, reasons for optimism are scarce. This does not imply that optimism is impossible, perhaps quite the opposite. The 2026 reader may wonder however what influence (if any) the recent aggravation of the crisis of multilateralism (as well as the simultaneous rise of adversarial and transactional sovereignism) would have on the demonstration of the author.

As noted above, the perspective of the course is normative in the sense that the search for coherence is presented as both desirable and possible. The temptation of normative disorder is only briefly considered, and then rejected, essentially on the ground that law and normative disorder are incompatible. Some might find this position not entirely convincing. There are several ways of approaching this issue, but one of them is to try to see what risks being lost in the pursuit of coherence (and thus of order). Alternative, non-modern forms of legality may come to mind. There are alternative presentations of the discipline that assign a predominant role to a radical acceptance of otherness (see, for example, the recent book by H. Muir Watt, reviewed here), from a pluralistic perspective. One of the criticisms then directed at contemporary private international law (at least at bilateralism) is its tendency to make room for alternative normativity only at the cost of its intense reconfiguration through the legality of the forum (through the lens or the rationality of the forum). From this perspective, the search for coherence (the process of rendering coherent) risks appearing as an extension of this rationalizing program. In reality, the opposition should perhaps not be overstated. As noted, L. d’Avout demonstrates methodological flexibility, without a priori privileging either bilateralism or unilateralism (or monism over pluralism, for that matter). Moreover, the coherence at play here is decentered from the forum, rather than imposed from an overhanging forum. In a sense, it is procedural and dialogical between States (as well as other “legal spheres”, i.e. alternative sources of normativity), rather than directly normative. Nevertheless, the demonstration rests on the idea that rationality is the inescapable horizon of law—an idea that maybe will face some pushback. Certain contemporary critiques of the international (legal) order (for instance, the decolonial scholarship, see this paper by S. Brachotte in a PIL perspective) tend instead to deeply deconstruct the very idea of legal coherence. These contemporary dynamics (the deep crisis of multilateralism and the teachings of the critical legal studies) obviously come from very different places and exist on different levels but they have in common a form of skepticism towards the concept of legal coherence. The reader may wonder to what extent they contradict the main thrust of the book, or if they can be reconciled with it, for instance through a reliance on, and reconfiguration of, horizontal (and intrinsically pluralist) modes of coordination.

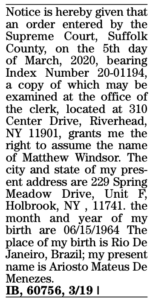

‘Recognition of a Foreign Judgment’ (HDE) no. 7.091/EX. The case concerned the recognition of a United States ruling changing the last name of a Brazilian national who had acquired US nationality. The Plaintiff sought recognition of (i) his US naturalisation and (ii) a ruling of the Supreme Judicial Court of Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which changed his name from ‘Ariosto Mateus de Menezes’ to ‘Matthew Windsor’.

‘Recognition of a Foreign Judgment’ (HDE) no. 7.091/EX. The case concerned the recognition of a United States ruling changing the last name of a Brazilian national who had acquired US nationality. The Plaintiff sought recognition of (i) his US naturalisation and (ii) a ruling of the Supreme Judicial Court of Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which changed his name from ‘Ariosto Mateus de Menezes’ to ‘Matthew Windsor’. The general course in private international law delivered at the Hague Academy of International Law by Louis d’Avout during the 2022 Summer Session was

The general course in private international law delivered at the Hague Academy of International Law by Louis d’Avout during the 2022 Summer Session was