A Short History of the Choice-of-Law Clause

Written by John Coyle, the Reef C. Ivey II Distinguished Professor of Law, Associate Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law

The choice-of-law clause is now omnipresent. A recent study found that these clauses can be found in 75 percent of material agreements executed by large public companies in the United States. The popularity of such clauses in contemporary practice raises several questions. When did choice-of-law clauses first appear? Have they always been popular? Has the manner in which they are drafted changed over time? Surprisingly, the existing literature provides few answers.

In this post, I try to answer some of these questions. The post is based on my recent paper, A Short History of the Choice-of-Law Clause, which will be published in 2020 by the Colorado Law Review. The paper seeks, among other things, to determine the prevalence of choice-of-law clauses in U.S. contracts at different historical moments. The paper also attempts to determine how the language in these same clauses has evolved over time.

Prevalence

The paper first traces the rise of the choice-of-law clause in the United States over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. It shows how these clauses were first adopted in the late 19th century by companies operating in a small number of industries – life insurance companies, transportation companies, and mortgage lenders – doing extensive business across state lines. These clauses soon migrated to other types of agreements, including prenuptial agreements, licensing agreements, and sales agreements. One can find examples of clauses in each of these types of agreements in cases decided between 1900 and 1920. It is challenging, however, to estimate what percentage of all U.S. contracts contained a choice-of-law clause at points in the distant past. To calculate this number accurately, one would need to know, first, the total number of contracts executed in a given year, and second, how many of these contracts contained choice-of-law clauses. From the vantage point of 2019, it is simply not possible to gather this information.

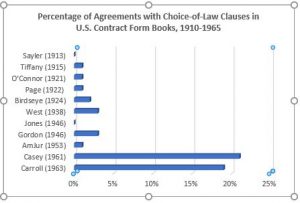

It is possible, however, to obtain a rough sense for the prevalence of such clauses by looking to books of form contracts. In an era before photocopiers – let alone computers and word processors – lawyers would routinely consult form books containing samples of many different types of contracts when called upon to draft a particular type of agreement. General form books typically contained hundreds of agreements, organized by type, that could be quickly and cost-effectively deployed by the contract drafter when the need arose. Since these books provide a historical record of what provisions were typically included from specific types of agreements at a particular time, they offer a potential means by which scholars can get a general sense for the prevalence of the choice-of-law clause in a particular era. One need only select a well-known form book from a given year, count the number of contracts in the form book, and determine what percentage of those contracts contain choice-of-law clauses.

Using this approach, I reviewed more than two dozen form books with the aid of several research assistants. The earliest form book dated to 1860. The contracts in that book contained not a single choice-of-law clause. The most recent form book dated to 2019. Sixty-nine percent of the contracts in this book contained a choice-of-law clause. The bulk of our time and attention was spent on form books published between these years. With respect to each book, we recorded the total number of contracts contained therein as well as the number of those contracts that contained a choice-of-law clause. When our work was done, it became clear that the choice-of-law clauses were infrequently used until the early 1960s, as demonstrated on the following chart.

While the clause was known to prior generations of contract drafters, it was not widely used until 1960. This is the year in which the clause truly began its long march to ubiquity.

There are many possible explanations for why the choice-of-law clause gained traction at this particular historical moment. One possibility is that the enactment of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) spurred more parties to write choice-of-law clauses into their agreements. Significantly, the draft UCC contained a provision that specifically directed courts to enforce choice-of-law clauses in commercial contracts when certain conditions were met. Although the UCC was first published in 1952, it was substantially revised in 1956 and was not enacted by most states until the early 1960s. It may not be a coincidence that one sees an uptick in the number of choice-of-law clauses appearing in form books at the same moment when many states were in the process of enacting a statute that directed their courts to enforce these provisions.

Language

The second part of the paper chronicles the changing language in choice-of-law clauses. This inquiry also presents certain methodological challenges. It is obviously impossible to review and inspect every choice-of-law clause used in the tens of millions of U.S. contracts that entered into force over the past 150 years. In order to overcome these challenges, I turned to a somewhat unusual source – published cases. Over a period of several years, I worked with more than a dozen research assistants to comb through such cases in search of choice-of-law clauses. Whenever we found a clause referenced in a case, we inputted that clause – along with the year the contract containing the clause was executed and the type of contract at issue – to a spreadsheet. When the work was complete, I had collected 3,104 choice-of-law clauses written into contracts between 1869 and 2000 that selected the law of a U.S. jurisdiction. We then set about analyzing the language in these clauses. In conducting this analysis, I ignored the choice of jurisdiction (e.g., New York or England). I was concerned exclusively with the other words in the clause (e.g., made, performed, interpreted, construed, governed, related to, conflict-of-laws rules, etc.).

This inquiry generated a number of interesting insights. First, I found that the Conflicts Revolution in the United States had little to no impact on the way that choice-of-law clauses were drafted. The proportion of clauses referencing the place where the contract was made or the place where it was to be performed remained constant between 1940 and 2000. Second, I found that while the proportion of clauses containing the words “interpreted” or “construed” similarly remained constant during this same time frame, the proportion of clauses that containing the word “governed” rose from 40 percent in the 1960s to 55 percent in the 1970s to 68 percent in the 1980s to 73 percent in the 1990s. It is likely that this increase was driven in part by court decisions rendered in the late 1970s suggesting that the word “govern” was broader than the word “interpret” or “construe” in the context of a choice-of-law clause.

Third, I found that it can be extremely difficult to predict when contract drafters will revise their choice-of-law clauses. In contemporary practice, one routinely comes across clauses that carve out the conflicts law of the chosen jurisdiction. (“This Agreement shall be governed by the laws of the State of New York, excluding its conflicts principles.”) This addition constitutes a relatively recent innovation; the earliest example of such a provision appears in a case decided in 1970. In the 1980s, roughly 8 percent of the clauses in the sample contained this language. By the 1990s, the number had risen to 18 percent. While there is no real harm in adding this language to one’s choice-of-law clause, the overwhelming practice among U.S. courts is to read this language into the clause even when it is absent. Its relatively rapid diffusion is thus surprising.

Conversely, very few contract drafters revised their clauses during this same time period to select the tort and statutory law of the chosen jurisdiction. This omission is baffling. U.S. courts have long held that contracting parties have the power to select the tort and statutory law of a particular jurisdiction in their choice-of-law clauses. It stands to reason that large corporations (and other actors in a position to dictate terms) would have raced to add such language to their clauses to lock in a wider range of their home jurisdiction’s law to be invoked in future disputes. The clauses in the sample, however, indicate that the proportion of clauses containing such language held constant at 1 percent to 2 percent throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The failure of this particular innovation to catch on during the relevant time period is likewise surprising.

Conclusion

The foregoing history looks to contract practice as it relates to choice-of-law clauses in the United States. There is no reason, however, why scholars in other nations could not deploy some of the same research methods to see if the choice-of-law clauses in their local contracts exhibit a similar trajectory. (Among other things, my paper contains a detailed discussion of methods.) Most well-resourced law libraries contain old form books that could be productively mined to determined when these provisions came into vogue across a range of jurisdictions. A review of such books could shed welcome light on the evolution of the choice-of-law clause over time across many different jurisdictions.

[This post is cross-posted at Blue Sky Blog, Columbia Law School’s Blog on Corporations and the Capital Markets]